This is another of those Callas performances that has acquired legendary status and so first a few details to set it in context. In the weeks prior to her appearance in Dallas Callas had been in dispute with Bing over the scheduled programme for her next Metropolitan Opera season. Though they had agreed the operas (Macbeth and La Traviata) they had not agreed the schedule and it transpired that Rudolf Bing had programmed the two operas to alternate with each other. Callas argued that this would be too hard on her voice, as the requirements for each were so different, asking that all the performances for one should be over before she embarked on the other. Bing avered that he was giving her ample time to rest inbetween operas and that he wasn’t prepared to change the schedule. His complete lack of understanding of the different needs of the tw roles was further exemplified by his suggestion that they replace La Traviata with Lucia di Lammermoor, an opera even further away from the demands of Macbeth. The wrangling continued for some time until Bing very publicly “fired Callas”, issuing a statement to the press in which he was photographed tearing up her contract. This on the eve of her first performance of Medea in Dallas.

Callas was incensed, granting a press conference to give her side of the story in her dressing room as she prepared for the prima, in which, as can be heard on this recording, she sings with a security and power that had recently eluded her. It was as if she was determined to show Bing and New York just what they were missing. The result is a performance of incredible fire and attack and, along with live performances from Florence and La Scala in 1953, one of her greatest recorded performances of the opera.

Dallas was certainly in a high state of excitement and the audience as heard on this recording can be noisy, applauding the sets at the opening of each act and granting Callas an ovation on her entrance that almost stops the show completely. She had opened the season with a beautiful new production of La Traviata directed by Zeffirelli. For Medea a completely Greek team had been assembled. The opera was to be directed by the eminent theatre director, Alexis Minotis (husband of acclaimed classical actress Katina Paxinou) with designs by Yannis Tsarouchis. Minotis, who was famous for his productions of Greek tragedies, in which he sought to recapture the style of expression and gesture used in the time of Aeschylus, was startled one day in rehearsal to see Callas do a movement he and Paxinou had been discussing for future use. Callas was kneeling in a frenzy, beating the floor to summon the gods. Minotis asked her why she had done it. “I felt it would be the right thing to do for this moment in the drama,” she replied. How she felt this, Minotis could not explain but he felt that certain things just flowed in her blood. Certainly one gets a sense of the sheer physicality of the performance from photographs and snippets of film from this and subsequent productions of the opera Callas did with Minotis in London, Epidaurus and at La Scala.

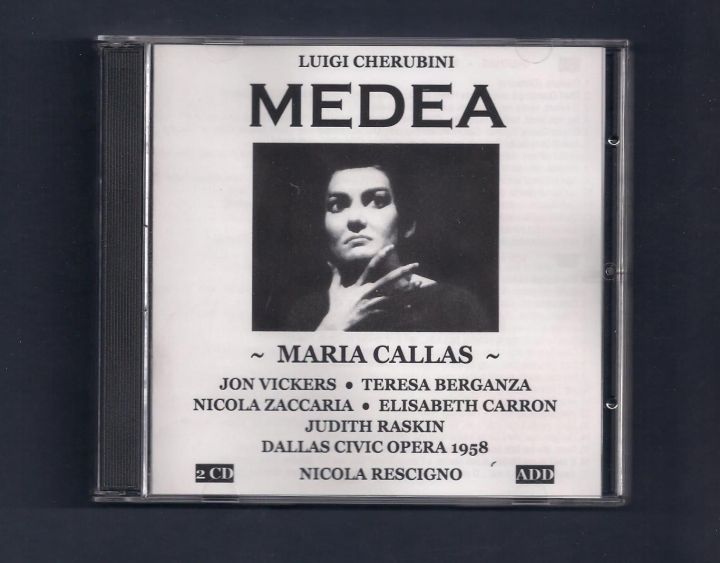

Nicola Rescigno, who prepared his own edition of the score, conducts a tautly dramatic performance, less classically inclined than Gui and Serafin, more akin to Bernstein at La Scala, and his cast is arguably the best ever assembled for a Callas Medea. Jon Vickers, who sang Giasone to her Medea not only here in Dallas, but in London, Epidaurus and at La Scala, easily outclasses the tenors in any of her other recordings and one senses the deep rapport that existed between them. Nicola Zaccaria is a firm, sonorous Creon and Elizabeth Carron, with her clear, bright soprano characterises well as Glauce. One also notes the presence of Judith Raskin, the soprano soloist in George Szell’s famous recording of Mahler’s 4th, as the First Handmaiden, making sure the performance gets off to a fine start. As Neris, the young Teresa Berganza (she was only 25 at the time) was making her US debut, singing her aria with a grave beauty. In later years, she related how Callas took her under her wing and how generous she was in making her acknowledge the applause after her aria. So much for the capricious, unreasonable prima donna, sacked by Rudolf Bing.

Callas herself is in blazing form, her entrance carrying with it a threat of menace that makes not only the people of Corinthrecoil in fear , but the listener too. However in her exchanges with Giasone (Ricordi il giorno tu la prima volta quando m’hai veduta?, which was always a special moment in Callas’s performances, wreathed in melting sounds) and in her plaintive singing of Dei tuoi figli we are made aware that it is love, not vengeance that brings Medea to Corinth.

As usual with Callas, her performance is cumulative and she will give as much attention to a line of recitative as to the evident high spots. As John Steane says in The Grand Tradition,

She will seize the moment, say of noble or tragic decision, summoning all the dramatic force of what has gone before, evoking our knowledge of what the consequences are to be and focusing precisely upon the moment on which all depends.

He was talking generally, but a superb example of this is in the two Act II duets with Creon and Giasone. In the duet with Creon, when she sings Che mai vi posso far, se il duol mi frange il cor? Come mai rifiutar un giorno al mio dolor, un sol dì al mio dolor? you know that she is formulating a plan, and then subsequently the duet with Giasone is a masterstroke of dramatic timing. Having got Giasone to demonstrate his love for his children, she sings the aside Oh gioia! Ei li ama ancor! Or so che far dovrò! with suppressed joy, before she launches into Figli miei, miei tesor in the most beseeching tones imaginable.

The last act is a lesson of contrasts. Momentarily weakening in the scene with her children, her cries of O figli miei, io v’amo tanto lke those of a wounded soul are silenced by the triumphal viciousness of La uccida, o Numi, l’empio giubilo. From there to the end of the opera, she is a cauldron of evil and revenge, the like of which you will never hear from any other singer.

The only alarming thing about this performance is that it is the last time we hear her sing with such power and confidence. There are still some wonderful performances to come, but nowhere does she display the kind of vocal security she does here, which makes it doubly fortunate that the performance has been preserved in sound.

I saw the production created for this Callas Medea with Olivero in both Dallas and Kansas City. The Kansas City performance exists on CD. My first exposure to Callas was a concert in Kansas City the same year as the Dallas Medea. Many years later I co-authored a Callas biography. Maria’s close friend David Stickelber, a Kansas City resident, graciously contributed invaluable information for my book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I looked for your book and found a copy on Abe Books UK. I’m not sure it’s ever been readily available over here in the UK.

LikeLike