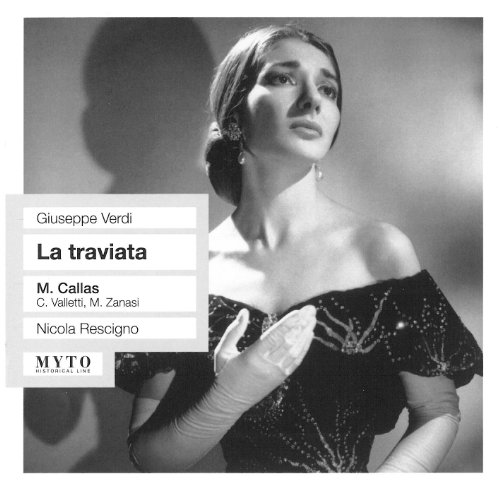

Violetta is one of Callas’s most famous, most exacting characterisations, and a role she sang more than any other except Norma. She first sang it in Florence in January 1951 and finally in Dallas in October 1958 (in a new Zeffirelli production) just a few months after this performance at Covent Garden. In between she had sung it all over Italy, in South America, in Chicago and at the Met, in Lisbon (just a few months before the Covent Garden ones) and of course there was the famous Visconti La Scala production, which changed for all times perceptions of Italian opera production.

Of all the roles in her repertoire, it was Violetta which underwent the greatest refinement, and it is a great shame that her only studio recording of it is the somewhat provincially supported Cetra performance of 1952, made before Visconti’s 1955 production, which substantially changed Callas’s views on performing the role. As you would expect, Callas still makes a profound impression in the set, but from Visconti onwards, her interpretations became ever more subtly inflected, more deeply felt, and her Violetta, especially as heard here at Covent Garden, has never been surpassed, let alone equaled.

It is often said that the role of Violetta requires three different sopranos; a coloratura for Act I, a lyric for Act II and a dramatic for Act III. A soprano comfortable with the demands of Act II and III, will struggle with the coloratura and high tessitura of Sempre libera, and, conversely a soprano happy with Act I’s pyrotechnics, won’t have the necessary weight of voice for the final Act. With Callas, no such provisos needed to be made, and, though earlier in her career, Sempre libera may have had more dash, ease and security on high, she could still, though slightly strained by its demands, sing it with dazzling accuracy in 1958. Furthermore, she invested the scales and runs with a hectic, nervous energy that made them much more than mere display.

The orchestral prelude of the Covent Garden performance starts with a small piece of operatic history. The microphone manages to pick up Callas quietly singing a couple of notes during the orchestral introduction. No doubt they were inaudible in the auditorium but their presence is one of the ways we Callas fans identify the performance from those first few bars. Indeed Terrence McNally’s play The Lisbon Traviata opens with the character of Mendy listening to the opening bars of this Covent Garden performance, then exploding, “No, no, no! That’s not Lisbon! It’s London 1958!” (I had the same reaction when I saw the play, until I realised it was intentional). Curiously, though, the notes are missing from ICA’s “first official” release. When I contacted ICA about it, they could offer no explanation, and their transfer is, in any case, somewhat muddy, so, for now, I would recommend the Myto transfer pictured above.

Whole tomes could be written about Callas’s interpretive insights in this performance, so inevitably right is her every utterance, so, in the interest of brevity, I will try to restrict myself to a few key points in each Act.

She starts forthrightly as if trying to convince everyone, including herself, that Violetta is over her recent illness, and her exchanges with Alfredo and the Baron have a delicious playfulness about them. Note in the Brindisi how accurately she executes those little grace notes and turns, usually blurred or ignored by other singers. Valletti, who is for the most part a model of elegance and style, misses them completely.

The brief moment when she almost faints, and then privately acknowledges her frailty is masterfully done, though she quickly regains her composure for the duet with Alfredo. Stunningly accurate is her singing Ah, se cio ver, fuggitemi, the coloratura flourishes invested with a carefree insouciance, that somehow also manages to express that she is already falling for Alfredo.

Left alone, the recitative takes us on a journey of conflicting emotions, until, wistfully and reflectively, she sings Ah fors’ e lui, her voice scarcely rising above a mezzo forte that draws the audience in, her legato as usual impeccable, the top notes floated in a gentle pianissimo that never obtrudes on the mood she has created. She herself tosses such thoughts aside in the Follie! Follie! section, pouring forth cascades of notes as she tries to convince herself that any ideas of love are pure whimsy.

Admittedly, top notes here and in the following cabaletta Sempre libera are a little tight and tense, but her coloratura is still brilliantly precise, and we note how she can make us hear the difference between simple scale passages and those separated into duple quavers. Alfredo’s interjection momentarily catches her off guard, and she launches into the reprise with even more gusto as she tries to block out his protestations. The unwritten final Eb is not exactly a pretty note (though no worse than Cotrubas’s on the Kleiber studio set), and it always seems a pity to me that she felt constrained to sing it at all, given that so many others, before and since, opt for the lower option. Nevertheless it rounds off an almost perfect rendition of this final scene.

Callas’s range of tone colour and her ability to express different thoughts and attitudes in a very short space of time are amply demonstrated in the first few exchanges of Act II. The single word Alfredo, when she asks as to his whereabouts is suffused with happiness. This quickly gives way to dignified outrage at Germont’s boorish outburst (Donna son io, signore, ed in mia casa) which in turn quickly softens when she realises that, as Alfredo’s father, the man deserves her respect (Ch’io vi lasci assentite, piu per voi, che per me). Later, when Germont questions her past, she responds with a voice of blazing affirmation, Piu non esiste. Or amo Alfredo, e Dio lo cancello col pentiemento mio. Oh come dolce mi suona il vostro accento is sung with a sweet, sadly misplaced, trust, which is quickly replaced with a touch of panic at Ah no! Tacete! Terribil cosa chiedereste certo. This whole scene, the recitatives and the duets, is a locus classicus of Callas’s art and a perfect example of her ability to invest a seemingly unimportant line, or even just a word, with significance.

Non sapete quale affetto is sung with mounting panic, like a butterfly caught indoors beating desperately against a windowpane, Gran Dio!, when Germont brutally suggests that she will age and Alfredo will not always remain faithful to her, in a tone of blank, pale despair. However the moment of true resignation, the moment Violetta accepts her fate, is enshrined in the one sustained note that leads into Dite alla giovine. Peter Heyworth saw this performance and reviewed it for The Observer. He describes the moment absolutely perfectly in his review.

But perhaps the most marvellous moment of the evening was the long sustained B flat before Violetta descends to the opening phrase of “Dite alla giovine”. This is the moment of decision on which the whole opera turns. By some miracle, Callas makes that note hang suspended in mid air; unadorned and unsupported she fills it with all the conflicting emotions that besiege her. As she descends to the aria, which she opened with a sweet, distant mezza voce of extraordinary poignancy, the die is cast.

One rarely comes across such brilliantly descriptive perception these days, and music criticism is much worse for it.

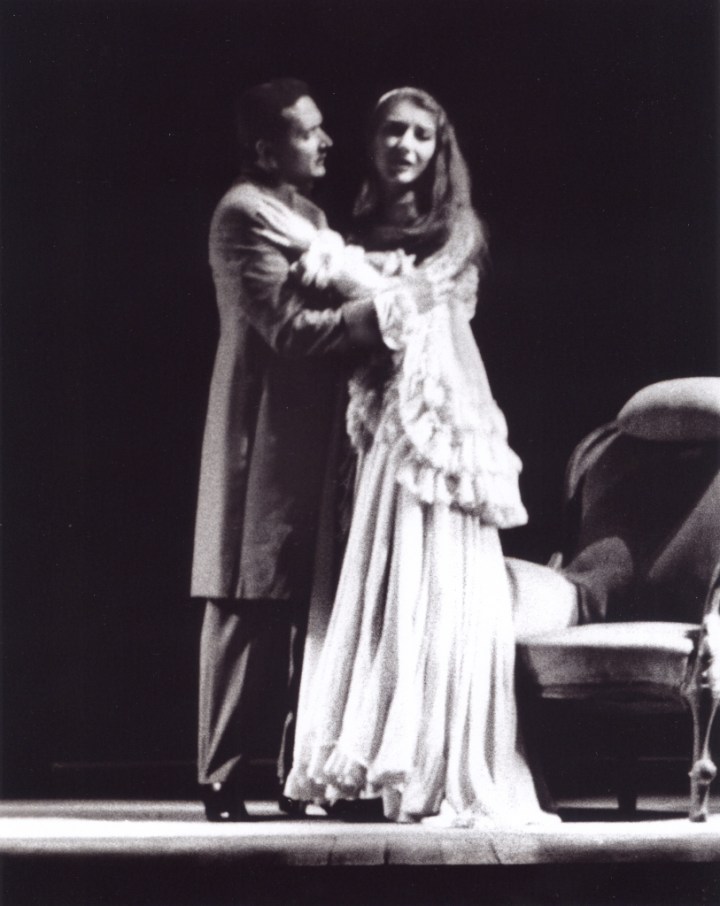

Imponete is uttered in a tone of total dejection, before the outpouring of emotion in which she begs Germont to embrace her like a daughter, and the scene in which she begs Alfredo to love her whatever happens is palpably, upsettingly real, Amami, Alfredo delivered with an intensity that makes you wonder how Alfredo could have doubted her for one second.

The scene at Flora’s party finds her almost sleep-walking, as she attempts to hide her heartbreak. When Alfredo forces out of her a confession that she loves the Baron, we can feel what it costs her, and the thread of sound with which she sings Alfredo, Alfredo, di questa core, after Alfredo has denounced her, is heart-wrenchingly moving.

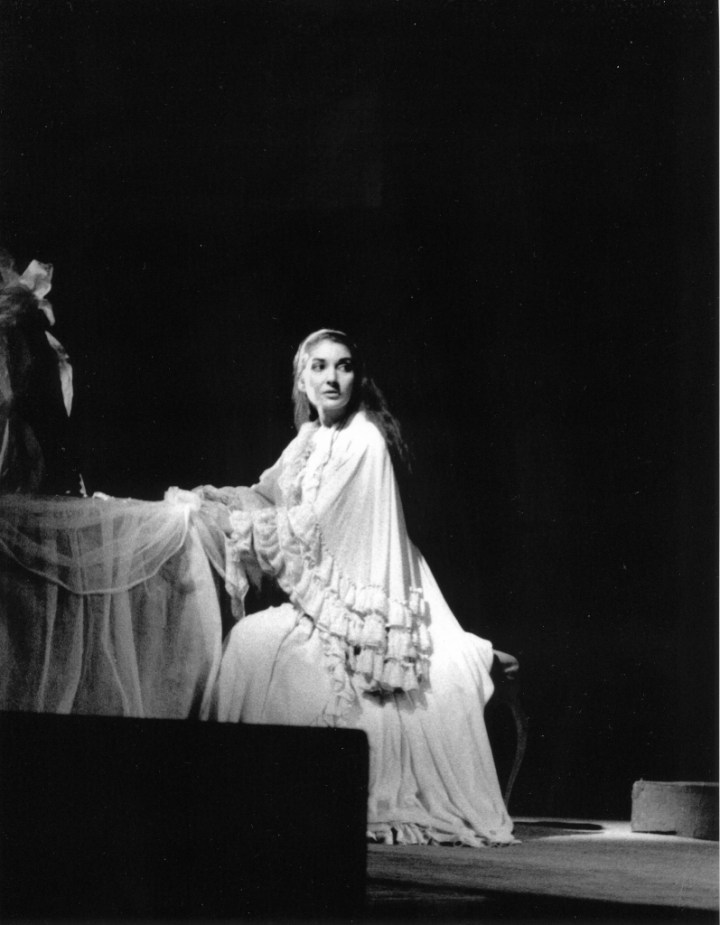

The last act is almost too much to bear, and even just thinking about it brings tears to my eyes. What other Violetta makes us feel so deeply her tragedy, her voice drained of all energy in the exchanges with Anina and the doctor? The tragedy really hits home with E tardi! after the reading of the letter; Addio del passato is delivered in a half tone of wondrous expressivity, its final A evaporating in the air. Rescigno recounts that the note kept cracking, and he would tell her to sing it with a little more power in order to sustain it, but she wouldn’t compromise. A firmer top A might have sounded prettier, but it did not reveal so well Violetta’s emotional and physical collapse.

The adrenalin rush of Alfredo’s entrance provokes more energetic attack, and she seems momentarily to recover, but the recovery is short-lived and the realisation that not even Alfredo can stop her from dying provokes an outburst of passionate intensity at Ah! Gran Dio morir si giovine. That intensity is short-lived though and the final section of the opera is delivered in a half-voice of ineffably sweet sadness. According to reports, as Callas’s Violetta rose to greet what she thought was new life, she literally became a standing corpse, her eyes staring sightlessly into the audience. We cannot of course see this on the recording, but the way she simply shuts the breath off on her final O gioia is an aural equivalent.

I wouldn’t want anyone to think though that spontaneity gets lost in the detail. The miracle of Callas is that not only does she achieve her effects with utmost musicality whilst closely adhering to what is in the printed score, but that she also does so as though the notes were coming newly minted from her mouth. Throughout she maintains her superb legato, never forgetting that, in Italian opera especially, it is the arc of the melody that is paramount. This surely is the art that conceals art.

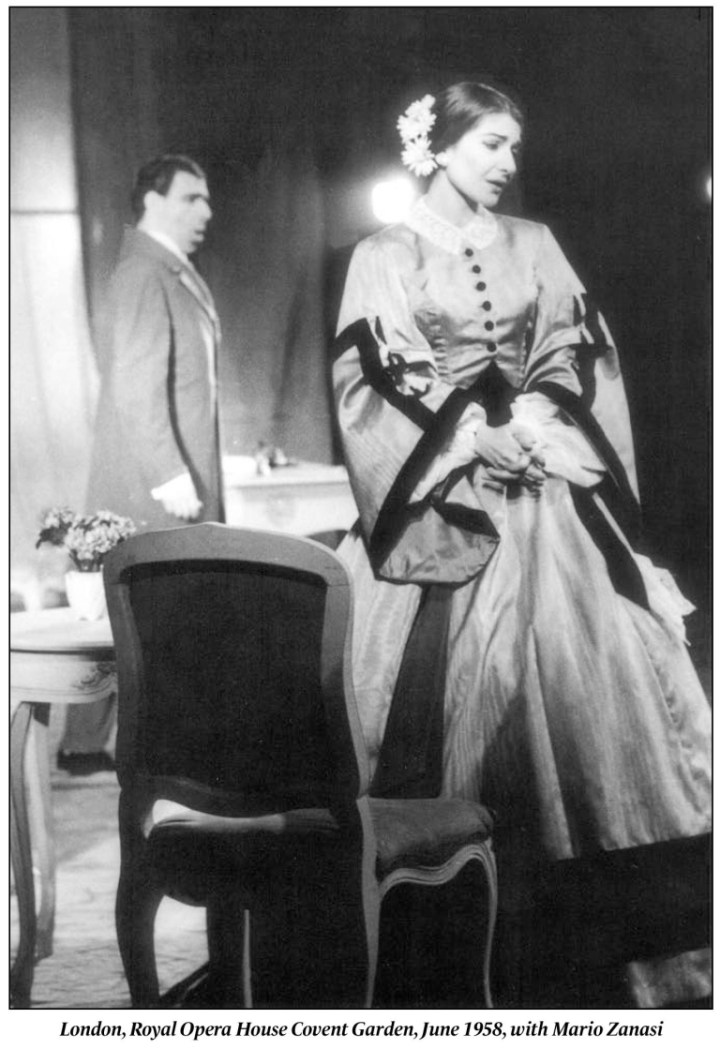

There are other reasons to treasure this set. Valletti, a Schipa pupil, sings with something of his master’s grace and elegance, though his tone is not as sappy as Di Stefano at La Scala or the young Kraus in Lisbon. Nonetheless he is a worthy partner, as is Mario Zanasi, who is my favourite of all the Germonts Callas sang with. His light baritone might sound a little young, but he is a most sympathetic partner in the long Act II duet, and a welcome relief from the four-square, over loud Germont of Bastianini at La Scala, however magnificent his actual voice.

Rescigno, as so often when accompanying Callas, is inspired to give of his very best, and the opera was cast with strength from the Covent Garden resident team, with Marie Collier as Flora and Forbes Robinson as the Baron.

Were I to be vouchsafed but one recording of La Traviata (I actually own six – four with Callas) on that proverbial desert island, then this would assuredly be it. In a performance such as this one forgets opera is artifice and what we are presented with is real life.