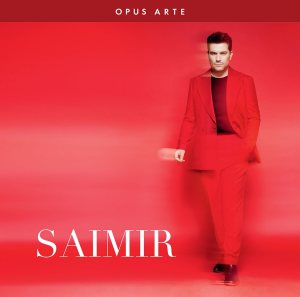

Ten years ago I saw Saimir Pirgu as the Duke in the Royal Opera House’s David McVicar production of Rigoletto. Though he looked splendid and dashing, he was utterly charmless and I found his singing stiff and monochromatic. Since then, he seems to have ventured into more dramatic repertoire, and this recital of mostly verismo arias comes as a follow-up to a 2015 album of more lyrical fare, which I haven’t heard.

The present recital was very well received by my colleague, Göran Forsling in October of last year (review) but I’m afraid I can’t join in with his praise. For a start, Pirgu’s basic production is terribly ingolata, so much so that his singing was giving me a sore throat. There is no freedom to the sound and, when I compare him to the greats of the past, from Caruso to Björling to Pavarotti, all I hear is his struggle to get the sound out. There is no ring at the top and the middle voice is forced, resulting in a distressing vibrato. Indeed, he sounds a good deal older than his forty-two years.

Added to that, he doesn’t really do anything with the music and here his conductor, Antonio Fogliani, must take some of the blame, for his conducting is dull and prosaic. Most of the arias on the disc are well known but, with so many other versions out there, this just isn’t competitive.

I tried listening to the recital several times, thinking that maybe it had something to do with my mood, but, no, each time my reactions were the same. I just couldn’t get past Pirgu’s basic vocal production and I found it difficult to relax and enjoy the music. I hate to be so negative, but this is a disc for fans of Pirgu only, if indeed they exist.

Contents.

- Puccini: Manon Lescaut – “Indietro!… Guardate, pazzo son”

2. Puccini: Tosca – “E lucevan le stelle”

3. Leoncavallo: Chatterton – “Non saria meglio… Tu sola a me”

4. Giordano: Andrea Chénier – “Colpito qui m’avete… Un dì all’azzurro spazio”

5. Puccini: Le villi – “Ecco la casa… Torna ai felici dì”

6. Puccini: Manon Lescaut – “Donna non vidi mai”

7. Cilea: Adriana Lecouvreur – “L’anima ho stanca”

8. Wagner: Lohengrin – “In fernem Land”

9. Berlioz: La Damnation de Faust – “Nature immense”

10. Tchaikovsky: Eugene Onegin – “Introduction”

11. Tchaikovsky: Eugene Onegin – “Kuda, kuda, kuda vi udalilis”

12. Puccini: Il tabarro – “Hai ben ragione”

13. Bizet: Carmen – “La fleur que tu m’avais jetée”

14. Puccini: Turandot – “Non piangere, Liù”

15. Jakova: Skenderbeu – “Kjo zemra ime”

16. Puccini: Tosca – “Recondita armonia” (with Vito Maria Brunetti (bass))

17. Giordano: Andrea Chénier – “Come un bel dì di maggio”

18. Puccini: Madama Butterfly – “Addio, fiorito asil”

19. Giordano: Fedora – “Amor ti vieta”

20. Sorozábal: La taberna del puerto – “No puede ser”

21. Puccini: Turandot – “Nessun dorma!”