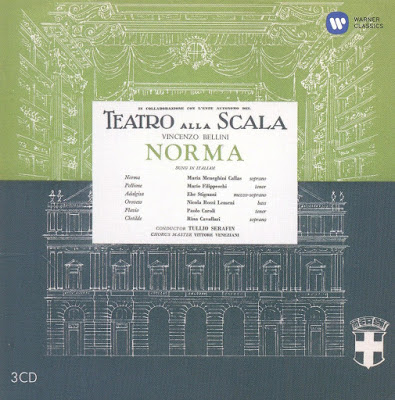

Recorded 23 April & 3 May 1954, Cinema Metropol, Milan

Producer: Walter Legge, Balance Engineer: Robert Beckett

Callas’s greatest role was Norma, the one that she sang more than any other, and one of three operas she recorded twice.

Though I did have this version on LP (when it was reissued in the 1970s), I never had it on CD. The 1960 version was one of the first LP opera sets I ever owned, and, not surprisingly, became one of the first I owned on CD. Later I acquired an Arkadia issue of the live 1955 La Scala, which I eventually replaced with the Divina Edition one of the same performance. As this was the Norma I most often pulled down off the shelf, I decided I didn’t really need another, so never got round to getting this 1954 recording on CD.

First impression on this set was the sheer presence of the voice. When Callas commandingly sings Sediziose voce she could almost be in the room with you and in fact the sound all round, orchestra and voices, is a lot better than some of the later operas; much less boxy with a real sense of presence. The second (in stereo) is better still of course, but the difference is relatively slight.

So how else does this compare to the second set, which I have already lavished such praise on? Well let’s start with the rest of the cast. Fillipeschi is, let’s face it, second-rate, and nowhere near as good as Corelli, his basic tone is thin and whiney and anything that requires any rapid movement finds him lacking, not that Corelli is much better in this respect, mind you, but there is the clarion compensation of his actual voice. Also I’m afraid I find it hard to join in the general round of praise for Stignani. Though the voice retains its firmness, she sounds too mature by this stage in her career, more like Callas’s mother than the innocent, young priestess she is supposed to be. Considering she was 20 years Callas’s senior at the time, it’s hardly surprising. Nor is her voice anywhere near as responsive as Callas’s, or as accurate, but then whose is? Not Ludwig’s, certainly, but I much prefer her more youthful timbre and her voice blends remarkably well with that of Callas; an unlikely piece of casting that paid off. Rossi-Lemeni’s tone tends to be woolly, but he is an authoritative Oroveso, more so than Zaccaria, whose tones are, however, more buttery.

As for Callas, there is no doubt that she is much more able to encompass the role’s vocal demands in this recording than the later one. I do miss certain more tender moments in the 1960 recording. Her entrance into Mira o Norma (Ah perche, perche), beautifully and touchingly understated is more moving than it is here, and in fact the whole duet works better with Ludwig, but when clarion strength and security are required then this set wins hands down. One might say we get more of the warrior in this one and more of the woman in the second. Given the security and power she evinces here, it seems strange that she does not take the high D at the end of Act I, as she did at previously preserved live performances, and as she would do again the following year in both Rome (also under Serafin) and Milan. It might seem a relief that she doesn’t attempt the note in 1960, but here I missed it.

Both recordings are essential of course. No other Norma in recorded history has come within a mile of her mastery of this role, the most difficult in the repertory according to Lilli Lehmann, and the one she sang more than any other. I am willing to believe that Pasta and Malibran were every bit as great, but I cannot believe they would have been better. I am indebted to John Steane yet again for putting things in a nutshell when he suggested that for Norma with Callas, one should go for the second recording, but for Callas as Norma, the first. Personally I’d want both, as the second, for all its vocal fallibility, searches deeper. I would also add the live 1955 from La Scala, the one in which voice and art find their purest equilibrium, and the one I would no doubt be clinging to if ever shipwrecked on that proverbial desert island.