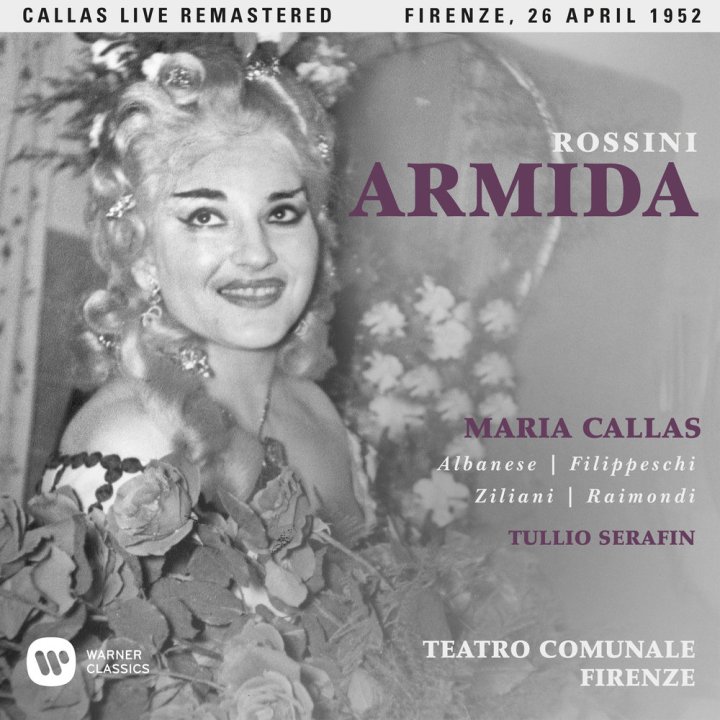

Florence and the Maggio Musicale, Fiorentino played a great part in Callas’s early career. It was at Florence’s Teatro Comunale that she debuted Norma, Violetta and Medea all of which were to become quintessential Callas roles. Other roles she sang there were Elvira in I Puritani, Armida (in which she had a spectacular success, though she never sang the role again), Lucia di Lammermoor (around the time of her first complete recording, which also used Florence resources), and her first Elena in I Vespri Siciliani, under Erich Kleiber. That year she also undertook the role of Euridice in Haydn’s Orfeo ed Euridice (its first ever performance, given at the tiny Teatro della Pergola, also under Kleieber).

The success of this production of I Vespri Siciliani finally made Antonio Ghiringhelli, the Sovrintendete of La Scala, Milan, who had for some reason taken an instant dislike to Callas, offer her her first season at La Scala. Later that year she would open the La Scala season in the same opera, I Vespri Siciliani, though this time under the baton of Victor De Sabata. For that same season she was also engaged for Norma and the role of Costanze in Die Entführung aus dem Serail, its first ever performance at La Scala. The opera was sung in Italian, and this was to be the only Mozart opera Callas ever sang. La Scala became her artistic, and geographical, home for the next seven years, and it became a period of extrordinary artistic achievement, allowing Callas to work with directors like Luchino Visconti, Franco Zeffirelli, Margarita Wallmann, Carl Ebert and Herbert Graf; conductors like Herbert von Karajan, Leonard Bernstein, Victor De Sabata and Carlo Maria Giulini. Most of her recordings were also made under the imprimatur of La Scala too, and she is to this day indelibly associated with the theatre.

No recording exists of the La Scala I Vespri Siciliani, so we are fortunate indeed that we have this recording from Florence. Like most of her live recordings from Florence, the sound has never been good, though in 2007 Testament issued a clearer transfer from tapes made for Walter Legge, who was using them to audition Callas. This Warner issue would appear to be a clone of the Testament transfer, with the overture, which wasn’t recorded for Legge, tacked on from another source. As such, I found it no better nor worse than the Testament issue, but, though the sound distorts and overloads quite a bit, it is worth persevering for Callas is in superb voice, in a wide-ranging role that takes her from a low F# in Arrigo, ah parli a un core to a top E in the Siciliana in Act V.

Lord Harewood was in the audience for one of the rehearsals of the Florence production and recalls precisely the effect of her entrance aria,

Act I of Vespri begins slowly; rival parties of occupying French and downtrodden Sicilians take up their positions on either side of the stage and glare at each other. The French have been boasting for some time of the privileges which belong by right to an army of occupation, when a female figure – the Sicilian Duchess Elena – is seen slowly crossing the square. Doubtless the music and the production helped to spotlight Elena, but, though Callas had not yet sung and was not even wearing her costume, one was straight away impressed by the natural dignity of her carriage, the air of quiet, innate authority which went with every movement. The French order her to sing for their entertainment, and mezza voce she starts a song, a slow cantabile melody; there is as complete control over the music as there had been over the stage. The song is a ballad, but it ends with the words “Il vostro fato è in vostra man” (Your fate is in your hand), delivered with concentrated meaning. The phrase is repeated with even more intensity, and suddenly the music becomes a cabaletta of electrifying force, the singer peals forth arpeggios and top notes and the French only wake up to the fact that they have permitted a patriotic demonstration under their very noses once it is under way. It was a completely convincing operatic moment, and Callas held the listeners in the palm of her hand to produce a tension that was almost unbearable until exhilaratingly released in the cabaletta.

Though we cannot see the impression she made, her very first words, Si canteró exude calm authority, with an undercurrent that suggests that, though she has agreed to sing, the French will not necessarily like what they hear. She starts almost mystically, gradually as Harewood describes, suffusing her tone with more pointed meaning at the words Il vostro fato è in vostro man. She then launches the cabaletta, Coraggio, su coraggio, almost sotto voce, building the tension as she starts to sing out with more force, her command of the wide leaps and coloratura staggering in its ease, the top of her voice gleaming and powerful. It is, as Lord Harewood suggests, a masterclass in how to use music to dramatic ends.

There is a good deal more to her Elena than that, though. She can be meltingly lyrical in the love music, such as in the beautiful mini aria Arrigo, ah parli a un core (though she only touches the low F# in its cadenza) and blithely suave and elegent in the Act V Siciliana, Merce, dilette amiche, notable for its light, breezy runs and an interpolated high E at its close. Few singers before or since can have so easily encompassed its vocal demands, whilst creating a character both sympathetic and imposing. There is never any doubt, from first note to last, that this Elena is an aristocrat; there are parallels here with Callas’s superb Leonora in Il Trovatore.

Of the supporting cast, Christoff, who also played the role at La Scala is a vocally resplendent and authoratative Procida, Mascherini a not particularly interesting Monforte. Giorgio Kokolios-Bardi, who sings the role of Arrigo, was a Greek tenor, whom Callas no doubt knew from her Athens Opera days. Occasionaly he phrases with a real sense of line, but just as often his singing lacks distinction. He was replaced by Eugene Conley at La Scala.

Erich Kleiber makes quite a few cuts in the sprawling score, but has a sure sense of its dramatic shape. There is a story that, at one point in rehearsals, he shouted out to Callas, “Maria, watch me,” to which she replied, “No, maestro, your eye sight is better than mine. You watch me.” Whatever the truth of this, they seem entirely at one in the performance, though I did wonder if Kleiber took the aforementioned Arrigo, ah parli a un core a tad to fast.

As I mentioned earlier in this review, I didn’t detect much improvement in the sound from the Testament issue of the performance, which in turn was quite a bit better than any heard before it was released. Nevertheless, this is essential Callas, and I wouldn’t want to be without it.