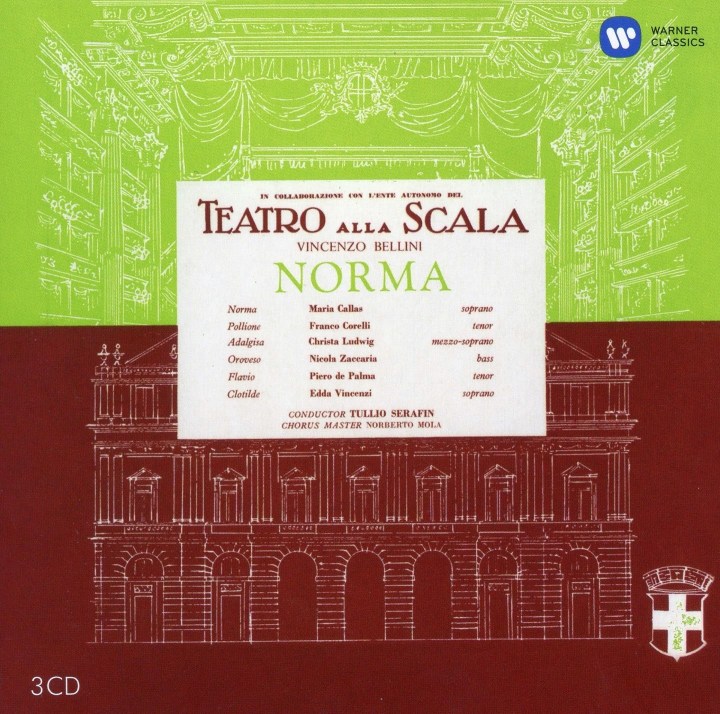

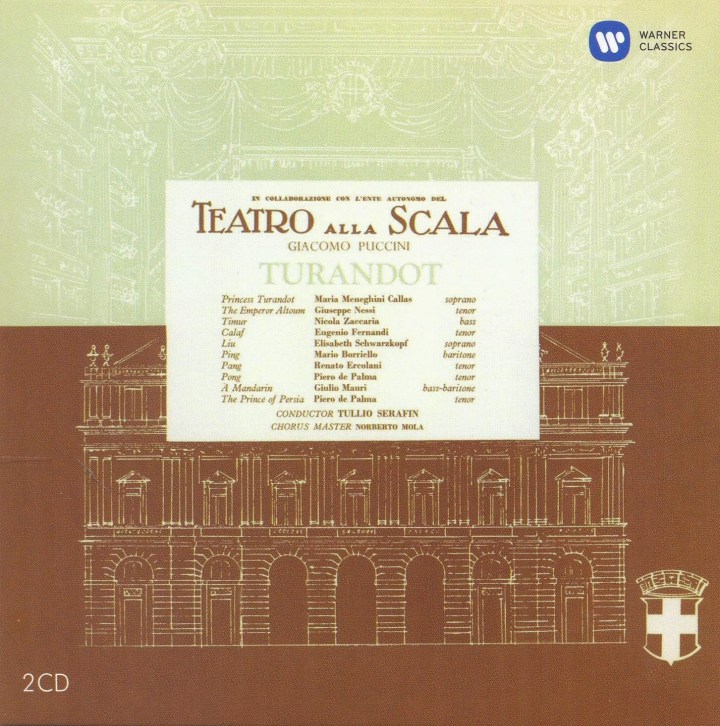

Recorded 9-13, 15 July 1957, Teatro alla Scala, Milan

Producers: Walter Legge and Walter Jellinek, Balance Engineer: Robert Beckett

1957 started well for Callas. She made two of her best recordings (Il Barbiere di Siviglia and La Sonnambula) and had a huge success as Anna in Anna Bolena at La Scala. The Iphigenie en Taurdie which followed may have been more of a succès d’estime but, though her colleagues were decidedly under par, she was superb and in good voice, as she was when La Scala took their production of La Sonnambula to Cologne in Germany.

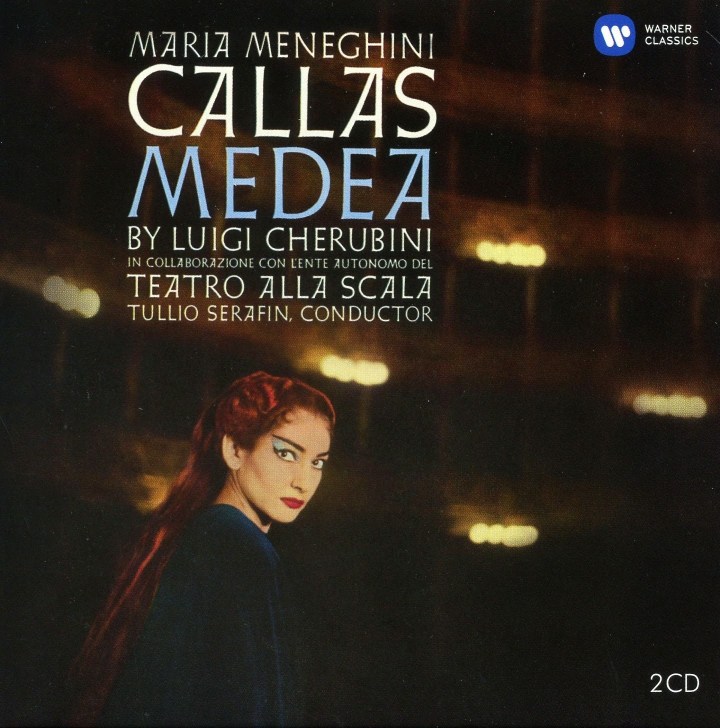

She then records two operas far less suited to her gifts (Turandot and Manon Lescaut), goes on to sing a concert in Athens, when she is decidedly not in her best voice, sings Amina again with the La Scala company in Edinburgh, where she sounds thoroughly exhausted, and then compounds the problem by recording Medea. The cracks are definitely beginning to show. After a few week’s rest, she is back on form for a Dallas Opera Inaugural concert (or appears to be on a recording of the rehearsal), and finishes the year well with a stupendous performance of Amelia in Un Ballo in Maschera at La Scala.

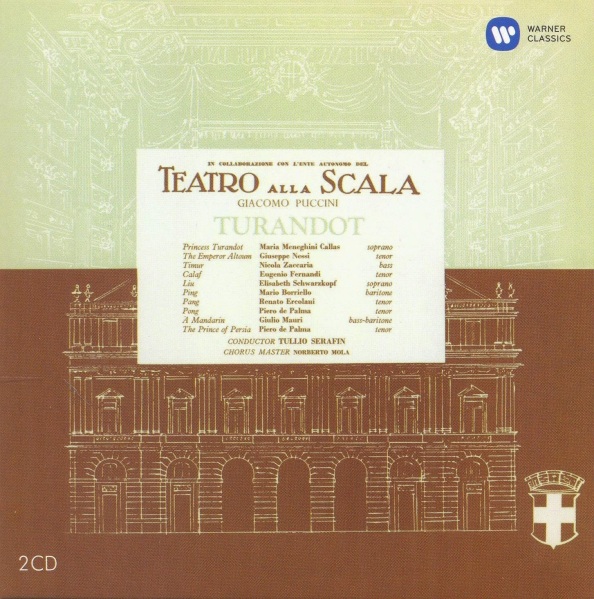

Turandot figured quite heavily in Callas’s early career. In 1948 and 1949 she sang it in Venice, Rome Caracalla, Genoa, Verona, Naples and Buenos Aires. She once said in interview that she dropped it as soon as she could, “because it’s not really good for the voice, you know.” All that exists from any of these performances are a couple of short extracts from the Buenos Aires performance, in which her voice is massive and free-wheeling, as far as one can tell through the execrable sound. By 1957 her voice has considerably pared down, and one might wish that she had recorded the role even a few years earlier when she sings a vocally secure and thoroughly commanding version of In questa reggia on the Puccini recital of 1954.

That said, I find the voice less wobbly and ill-supported than I do in the Manon Lescaut, which followed, on which, to my ears, she sounds exhausted, for all her customary musical imagination and insights. She is more secure in this Turandot but she doesn’t really disguise the effort it costs her. Where Nilsson and Sutherland, and Eva Turner before them, soar, Callas is more earth bound. That said, she makes a psychologically more complex heroine than any of them, her singing more subtly layered than we have come to expect from a Turandot. Hear how she vocally points the finger at Calaf in In questa reggia when she sings Un uomo come te, the almost mystical recounting of the story of Lou-u-ling. The first signs of Turandot’s vulnerability come in the Riddle Scene, anxiety creeping into her voice at Si la speranza che delude sempre, and her pleading to her father is almost in the voice of Butterfly, suddenly a daughter trying to get round her father. There are signs of her vulnerability too in the brief scene with Liu, when she asks, Che posa tanta forza nel tuo core, mirroring Liu’s response with her repetition of the word L’amore. Even the last scene is less of an anti-climax than it usually is. When she sings Che e mai di me? Perduta, we know that she is conquered, and her final aria Del primo pianto is sung with a wealth of detail. For all the evident strain the role makes on her resources, it is a great performance, and she is far less stressed by its demands than Ricciarelli is on Karajan’s recording.

The rest of the cast is interesting. Many have opined that Schwarzkopf sounds as if she had wandered in from the wrong opera, but I like her finely nuanced and beautifully shaded Liu. She is particularly impressive in her exchanges with Turandot and in the mini aria Tanto amore, effecting a wonderful diminuendo on the line Ah come offerta suprema del mio amore. What a pity this is the only time the two most intelligent sopranos of the post war period ever sang together. Fernandi, a strange choice considering he was very little known at the time, and hardly at all since, is rather better than his lack of reputation suggests. Not as exciting as a Corelli (why on earth was he not engaged?) he nevertheless sings a valid Calaf, often phrasing with distinction. Not the best Calaf on record certainly, but not the worst either. Zaccaria is a sympathetic presence as Timur, Ping, Pang and Pong all characterful. There is also a connection with the first ever performance as Nessi, who sings the Emperor, created the role of Pang.

Serafin’s conducting is excellent, urgent and well-paced. What a pity that he doesn’t have the benefit of modern stereo sound, which this of all operas really cries out for. The sound here is, to my ears anyway, less boxy than the sound for Manon Lescaut, though it is not as open as, say, the De Sabata Tosca, which was recorded four years earlier. This Warner pressing sounds a good deal better than my 1997 Callas Edition, with Callas’s voice far less shrill in the upper reaches. It may never be anyone’s library choice for the opera, but I would not want to be without the insights Callas brings to the role. It is, in many respects, a more thoughtful rendering of the score than we often hear.