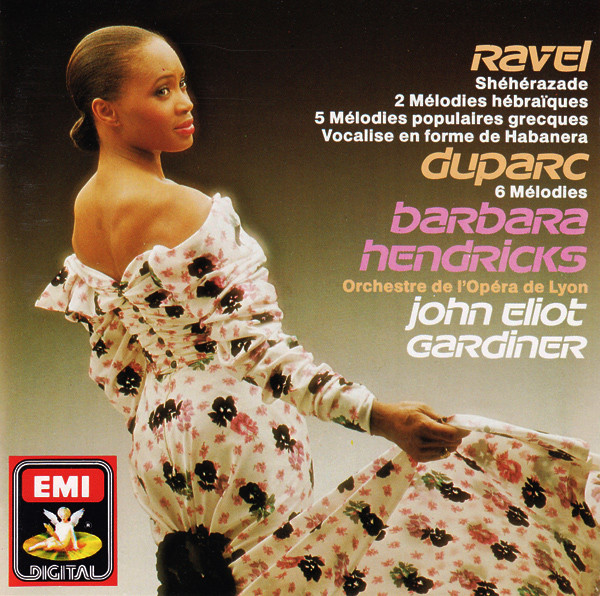

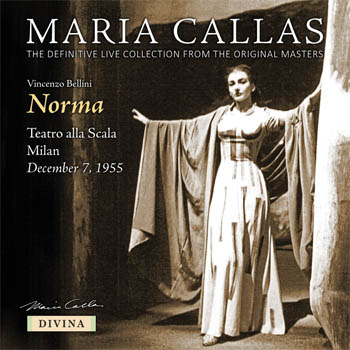

1955 had been a spectacular year for Callas, though its beginning was inauspicious. She had been scheduled to start the year singing one of her speciality roles, Leonora in Il Trovatore, at La Scala, but Del Monaco, who was to have sung Manrico pleaded indisposition, though oddly he felt well enough to sing Andrea Chénier (who knows the vicissitudes of tenors), so La Scala made a substitution. Callas could have stepped down, but learned the role of Maddalena in a few days. The opera, a La Scala favourite, had a big success, but the role was hardly one in which her rarified gifts could shine, and is something of a curiosity in the Callas cannon. Thereafter she went from one major success to another. She sang Medea in Rome and followed it with three productions at La Scala, which have entered the realms of legend, the Visconti productions of La Sonnambula and La Traviata, and, by way of contrast, Zeffirelli’s production of Il Turco in Italia. During the summer she recorded Aida, Madama Butterfly and Rigoletto then in September she had a massive success in Karajan’s La Scala production of Lucia di Lammermoor, when the opera toured to Berlin. The autumn saw her back in Chicago for her second season, where she sang Elvira in I Puritani, Leonora in Il Trovatore (perfection according to her co-star Jussi Bjoerling) and her only stage performances of Madama Butterfly. Truly 1955 had been her annus mirabilis and she closed it with what, by common consent, is the greatest recorded performance of her signature role, Norma.

First a word about the differences between this Divina transfer and most others you will hear. Divina’s remaster is from a first generation master tape and the sound is very good, certainly the best I’ve heard. As the first fifteen minutes were not recorded, like other companies Divina have included music from another performance, but whereas other labels do not credit it, Divina tells us they used a 1965 performance under Gavazzeni for the overture and Oroveso’s first aria, and the Rome broadcast of 1955 under Serafin for part of the recitative before Pollione’s Act I aria. There was some radio interference in Norma’s long solo at the beginning of Act II, and most issues substituted the same scene from the Rome broadcast of the same year, but Divina have left it as it stands to retain the integrity of the La Scala performance, and so as not to lose some of Callas’s most moving singing. It lasts only a few seconds and is easy to live with.

The La Scala season starts every year on December 7th, and for the fourth time in five years, Callas had been given the honour of a new production to open the season. The last time she had sung Norma there was in 1952, the year she first became a permanent member of the La Scala company. The La Scala years saw a period of incredible artistic achievement and there is no doubt that by this time Callas had become the reigning queen of La Scala. The new production was by Margherita Wallman, with designs by Nicola Benois and the starry cast included Mario Del Monaco as Pollione, Giulietta Simionato as Adalgisa and Nicola Zaccaria as Oroveso.

Callas is in fabulous form from the outset, stamping her authority on the performance, and the Druids, in her opening recitatives, her voice taking on a veiled, mysterious quality when she sings about reading the secret books of heaven, before singing a mesmeric Casta diva. The repeated As up to B harden slightly in the first verse, but that hardness has dissipated by the second verse and therafter the voice seems to be responding to her every whim. The linking recitative between cavatina and cabaletta was always a high point of her performances, with that wondrous change of colour at Ma punirlo il cor non sa, leading her into the cabaletta. It’s a jaunty tune with plenty of opportunity for display, but Callas somehow invests it with a private melancholy available to few others. I find it impossible to think of the words Ah riedi ancora, qual eri allora without hearing Callas’s peculiarly plaintive voice in my mind’s ear.

The duets with Simionato are also high points of the performance. The two singers first appeared together in Mexico in 1950 and became life long friends. Before these La Scala performances, they had sung together in the opera in Mexico, Catania, London (in 1953) and Chicago. Though the pairing of Callas with Stignani had become a famous one, Simionato was a better fit for the role than Stignani, who both looked and sounded too mature, and no downward transpositions had to be made to accomodate her. Furthermore their voices blended well, and you can sense the deep rapport that existed between them after so many performances together. It is great cause for regret that Simionato was contracted to Decca and therefore never appeared on any of Callas’s studio recordings.

There are so many things to cherish in this first duet, particularly the wistful way Callas’s Norma recollects the dawning of her love for Pollione and then the fullness of heart with which she consoles Adalgisa at Ah tergi il pianto. However the most arresting moment is in the cabaletta to the duet when she hits a top C forte, then makes a diminuendo on the note before cascading down a perfect ‘string of pearls’ scale, eliciting audible gasps of disbelief from the audience.

Having been all warmth in the duet, her voice flashes out in anger in the trio, the coloratura flourishes hurled out with terrific force, the top Cs like scalpel attacks. The act comes to an exciting end as Callas takes a thrilling, rock solid top D, which she holds ringingly for several bars.

The opening of Act II, a mixture of recitative and arioso akin in some ways to Rigoletto’s Pari siamo, always provoked some of Callas’s most moving singing. What other singer matches her range of tone colour in this scene? I’m thinking of the hard tone at schiavi d’una matrigna when she contemplates the fate of her children at the hands of a stepmother, and the way she drains the tone of colour at un gel mi prende e in fronte mi si solleva il crin so that it becomes a literal expression of her hair standing up on end. This leads to wonderfully tender singing as she looks at her sleeping children, and of course ultimately she cannot bring herself to kill them, her voice drenched with maternal love at son i miei figli.

The following duet, one of the most famous in the bel canto repertoire is, even more than the Act I duet, a perfect example of two artists at one with each other, their voices intertwining and their timing perfect. Not unsurprisingly it provokes rapturous applause from the audience.

Callas’s performances were always cumulative and the final scene is almost unbearably moving as Callas takes us through the gamut of emotions, from the almost youthful joy with which she sings Ei tornera spinning out the melisma on come del primo amor ai di felici, through suppressed anger and barely contained rage to ultimate peace and magnanimity, heart-wringinly moving in her final plea for her children. But what we should always remember is how musically her effects are made, her phrasing and the way she shapes the musical line, her sense of rubato unparalleled. Another moment that has entered the history books is her singing of the words son io when Norma confesses her guilt. Apparently she would simply take the wreath from her head and you can almost hear the moment she does it. The audience respond with a sort of corporate moan. Was Ponselle ever as moving as this? Was Pasta? We will never know, but at least with Callas we have recorded evidence. So much is Callas’s way with the role imprinted on my subconscious that inevitably I find all others wanting. Her Norma is so complete, so all enveloping that it remains unchallenged to this day and we are fortunate indeed that this performance, which captures that moment in her career when art and technique reached their truest equilibrium, was captured in sound.

For the rest, Simionato is arguably the best Adalgisa Callas ever sang with and is in terrific form here. Zaccaria is a sympathetic and sonorous Oroveso. Del Monaco makes up for his lack of coloratura with a voice of heroic, clarion splendour and Votto, though he pales next to Serafin, is the perfect accompanist, which, with such a cast, is perhaps all he needed to be.

Great Normas have always been thin on the ground, though all sorts of unsuitable singers appear to be attempting it these days, but let no one think they have truly heard the opera until they have heard a performance with a great protagonist. The studio recordings have their value in enjoying better sound, but I have no hesitation giving this one the prize as the best of all Callas’s recorded Normas.