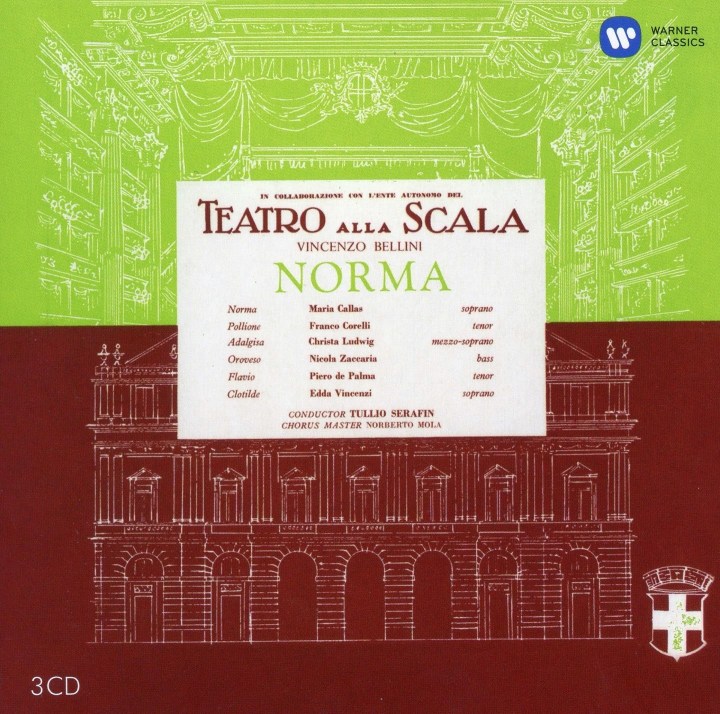

Recorded 9-12 July 1955, Teatro alla Scala, Milan

Producer: Walter Jellinek, Balance Engineer: Robert Beckett

Though recorded in 1955, release of this disc was delayed until 1958. Callas did not approve the arias from La Sonnambula for release and, when the recital was finally issued, it was made up with arias from the complete sets of I Puritani and La Sonnambula. EMI did eventually issue the Sonnambula arias, but not until 1978, on an LP called The Legend which included other unreleased material.

It’s true, there is a slightly studied air about the performances of them (and a chorus would no doubt have done much to enliven the proceedings), but her singing is unfailingly lovely. One misses that stunning cadenza between the two verses of Ah non giunge, with its stupendous ascent to a high Eb, which we get in both the studio and Cologne performances, and both cabalettas are over simplified, completely free of the flights of fancy Bernstein encouraged her to indulge in at La Scala. Serafin had apparently refused to let her do them. Maybe that is the reason she eventually rejected them. I’m glad I’ve heard them, but her Amina is better represented in the various live performances and the complete studio performance.

The Medea and La Vestale arias are more successful. Medea, of course, became one of her greatest stage successes. The opera was almost completely unknown when she first sang it in Florence in 1953 under Gui, but such was her success in the role that La Scala scotched plans for a revival of Scarlatti’s Mitridate Eupatore later that year and replaced it with the Cherubini opera. Callas’s singing of Dei tuoi figli la madre abounds in contrasts, reminding us that this is an appeal to Giasone. Callas reminds us that it is love, not revenge, that brings Medea to Corinth; notable here the softening of her tone at the repeated pleas of Torna a me, the pain in the cries of Crudel.

The arias from La Vestale are reminders of her one traversal of the role of Giulia at La Scala in 1954, in a stunning production by Visconti, which marked the emergence of the new, slim Callas, and the start of a whole new era, which resulted in the acclaimed Visconti productions of La Traviata, La Sonnambula and Anna Bolena. Tu che invoco is notable for its long legato line, and the intensity she brings to the turbulent closing section, where her voice rides the orchestra with power to spare. O nume tutelar brings back memories of Ponselle, but Callas in no ways suffers by the comparison, her legato as usual superb, and the aria sung with a classical poise and sure sense of the long line. O caro ogetto has the same virtues.

There exists a complete recording of that La Scala La Vestale, but it is in such wretched sound, that this recital is valuable for Giulia’s arias alone. Her Medea and Amina are better represented elsewhere.