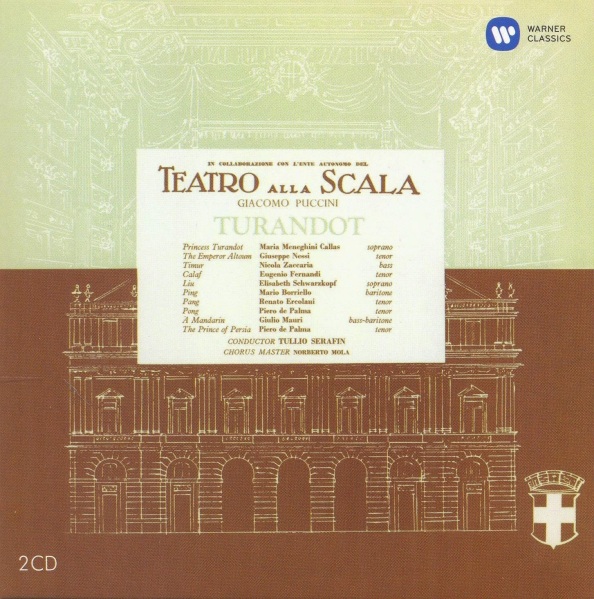

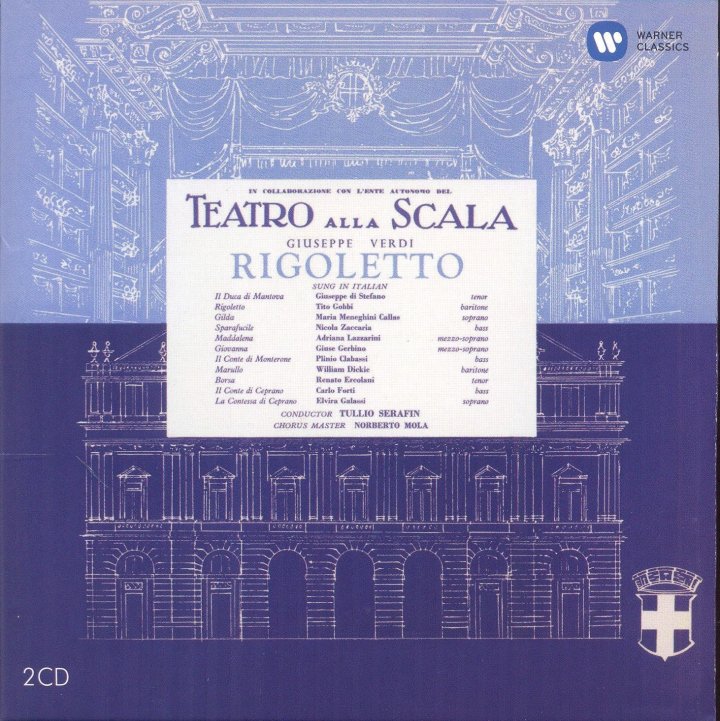

Recorded 3-16 September, 1955, Teatro alla Scala, Milan

Producer: Walter Legge, Balance Engineer: Robert Beckett

Gilda is another role one would not readily associate with Callas. She did sing it on stage for two performances in Mexico in 1952, but, unhappy with her performance, never sang it again except for this recording made in 1955. The Mexico performances are a bit of a mess and sound under-rehearsed, but Callas is superb, and one notes how it is often she who keeps the ensemble together, even though she was so blind on stage she could never see the conductor. It is actually something of a tragedy that she didn’t sing the role more often. If she had, then people may have rethought the role of Gilda, as they did that of Lucia. It is usually sung by a light voiced lyric coloratura, who manages Caro nome well enough, but can’t really muster the power to dominate the ensembles in the last two acts, as she should. It’s something I’ve noticed myself. Not so long ago I saw the opera at Covent Garden with Aleksandra Kurzak as Gilda. She looked ideal, convincingly acted the ingénue, sang a wonderful Caro nome, but tended to be drowned out in the final act, especially in the storm scene.

No problem there for Callas of course, but the miracle is not that she can sing out with a but more power when needed, but that she remains in vocal character when she does. She doesn’t suddenly sound like Norma or Tosca, but continues to think upwards in a voice somehow cleansed of all those heavier associations.

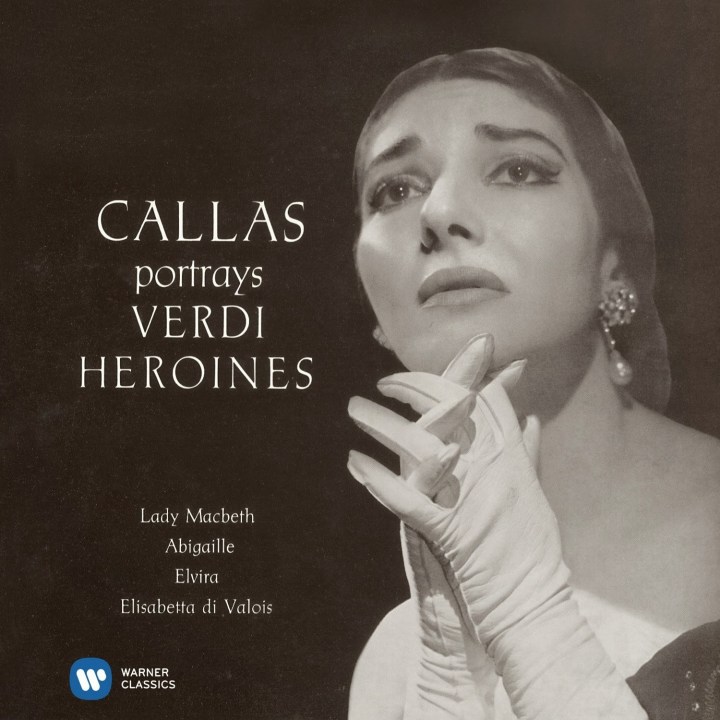

I often think it odd that when people talk about Verdi sopranos, it is the voices of Tebaldi and Leontyne Price they have in mind, but could either of those sopranos have sung Gilda, or Lady Macbeth, or any of Verdi’s early roles? Tebaldi may have sung Violetta, but it wasn’t a natural for her, the coloratura in Sempre libera smudged (and transposed down in live performances). Nor did Tebaldi sing the Trovatore Leonora on stage, as the role lay too high for her. Price did of course, and she was an appreciable Leonora, though she doesn’t sing with the same degree of accuracy as Callas. Callas, on the other hand, sang with equal success Gilda and Lady Macbeth, Abigaille and Elisabeth de Valois, Elena and Aida, both Leonoras, Amelia and Violetta, all on stage not just in the studio, and one regrets that she didn’t get the chance to sing more of Verdi’s early operas. What a superb Luisa Miller she might have made, or Odabella in Attila, Griselda in I Lombardi, or virtually any of those early Verdi heroines. Maybe, after all, it is Callas who is the ideal Verdi soprano.

But back to this Rigoletto, in which Callas yet again completely inhabits an uncharacteristic role. In the first two acts, she presents a shy, innocent young girl, with a touch of wilfulness that explains her disobedience to her father. In the duet with Rigoletto, we feel the warmth of her love for him, and in the one with the Duke, the shy young girl awakening to passion. You can almost see her blushes when the Duke first appears to her. She was asked once why the single word uscitene resounded with such a strange colour. “Because Gilda says go, but wants to say stay,” was her simple answer. Actors might be used to such psychoogical distinctions but it is rare indeed to find it in singers. Caro nome is not just a coloratura showpiece, but a dreamy reverie, and ends on a perfect rapturous trill as she exits the stage. In Act III her voice takes on more colour (Ah, l’onta, padre mio) and it is Tutte le feste that becomes the focal point of her performance, her voice rising with power to the climax (nell’ansia piu crudel) as she describes the horror of what happened, and note how at the opening she matches her tone to that of the cor anglais introduction. She has the power to ride the orchestra in the storm scene in the last act, and the final duet with Gobbi is unbelievably touching. As usual her legato is superb, phrases prodigious in length, shaped and spun out like a master violinist. It is a great pity she didn’t sing Gilda more often, for it is a considerable achievement.

There are other reasons to treasure this performance of course, chief among them being Gobbi’s superbly characterful, endlessly fascinating and heartrending performance of the title role. Gobbi and Callas always had a striking empathy, and the three duets for father and daughter in this opera, gave that relationship full rein. Some have remarked that Gobbi’s voice was not a true Verdi baritone (whatever that means), but, like Callas, he was successful in a range of different Verdi baritone roles, his most famous probably being Rigoletto. Who has ever matched Gobbi in tonal variety and vocal colour, and psychological complexity? None that I can think of. Pari siamo is superbly introspective and then in Cortigiani! he lashes out like a wounded animal, before breaking down in accents that are pathetically heartrending. To those who say he could not sing with beauty of tone, I would say there are plenty of moments in the score which refute that assertion, the Piangi section of the Act II duet, where he spins out a pure legato which is both musical and shatteringly moving, being a case in point.

Di Stefano may not be quite in their class, and there are certainly more elegant Dukes on record, but he sings with enormous face and charm. One can imagine why Gilda would be captivated by this Duke. He can be musically inexact (some of the tricky rhythms in Act I go a bit awry), but his voice is in fine shape, and he sounds both charming and sexy, which is as it should be. Nor does he play down the casual cruelty that lies at the heart of his character. I’d say it’s one of his best recordings.

Serafin’s conducting is in the best Italian tradition, both lyrical and dramatically incisive. He is totally at one with Callas and Gobbi in the duets, giving them ample time to make their dramatic points, but whips up quite a storm in the finale to Act II.

The sound is truthful and clear, the voices wonderfully present, and, as in all the Warner sets so far, sounds excellent on my system.

Years ago I remember an acquaintance, not really a voice fan (or a major opera fan, for that matter), asking me which recording of Rigoletto I recommended. He had the Giulini, and quite enjoyed it, but thought there was something missing. I warned him that some were allergic to Callas’s voice, but lent him my set anyway. A couple of days later he excitedly returned it to me, having ordered the recording for himself. “Fantastic,” he said, “Exactly what I was looking for. Suddenly the whole opera came to life.” Well you can’t ask for much more than that.