Operetta is probably not as popular now as it was around the middle of the last century when amateur productions of popular operettas were ubiquitous. Indeed, back in the 1950s and 1960s my father was musical director of several local operatic societies, conducting a regular fare of Lehár, Strauss and Offenbach alongside American musicals by Rodgers and Hammerstein and the like. Nowadays you’d be more likely to encounter shows by Lloyd Webber or Schönberg & Boubil, or one of the now popular jukebox musicals. Even The Merry Widow and Die Fledermaus, once in the regular repertoire of our professional opera companies, are seldom performed, at least here in the UK.

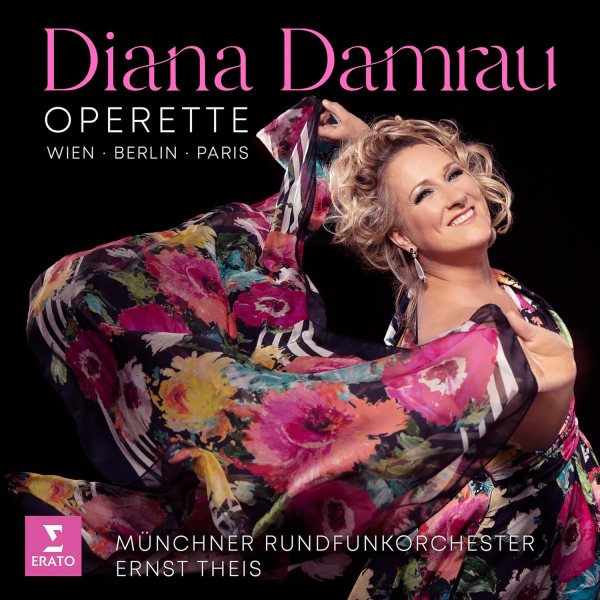

Maybe the tradition is more alive in Germany and Austria because the Münchner Rundfunkorchester under Ernst Theis here put in splendidly stylish performances of all the chosen arias and duets, sounding totally idiomatic in a wide-ranging programme of music mostly from Vienna, but also taking in Berlin and Paris. There is also some wonderful solo violin playing from, I presume, the leader of the orchestra, notably in the aria from Lehár’s Zigeunerliebe, which exudes a fiery, gypsy passion.

The booklet notes take the form of a (slightly twee) conversation between Damrau and her childhood friend Elke Kottmair, who spent 12 years with the Dresden State Operetta and upon whose expertise and knowledge Damrau drew when compiling this collection. Kotke and mezzo-soprano Emily Sierra join Damrau for a trio from Johann Strauss’s little-known Das Spitzentuch der Königin, and she has also enlisted the support of Jonas Kaufmann for a duet from the same operetta, as well as duets from Stolz’s Im weißen Rössl and the famous Im chambre séparée from Heuberger’s Der Opernball, which some of you may know better as a soprano solo.

These help to add a bit of welcome variety to the programme and here I have to make something of a confession. I have never really liked Damrau’s voice, finding it rather hard and unrelenting. It has never been a particularly luscious instrument, but, to my ears, it is now sounding rather dry and, in the middle register, a little shrewish, where one really wants something more sensuous. Furthermore, when she tries to be charming, she can become excessively coy. Comparing her and Susan Graham in J’ai deux amants from Messager’s L’Amour Masqué, (included in her disc of French Operetta arias) it is to find Graham much warmer and more sexily playful.

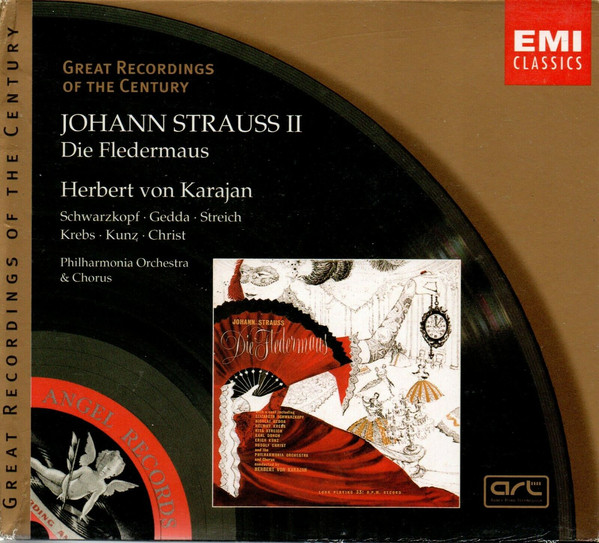

When it comes to the Viennese items, you only have to listen to Elisabeth Schwarzkopf in Ich schenk’ mein Herz from Millöcker’s Die Dubarry or in Im chambre séparée to understand the real echt-Viennese style. I doubt there has ever been a finer recital of operetta arias ever recorded, though I also recall a lovely disc by Barbara Bonney, accompanied by solo piano, which is also well worth investigating.

For those who respond better to Damrau’s voice than I do, I have no doubt you will find much to enjoy. I did too. I just wish I had a more positive reaction to the singing.