Callas’s second stereo recording of Lucia di Lammermoor, which I reviewed when it was reissued by Warner , has always been considered one of her best from a sonic point of view, so, as someone who has not always been totally convinced by some of Andrew Rose’s re-mastering methods, I wondered how, if at all, the sound could be improved upon. Let me say straight away that I found this latest addition to Pristine’s Callas catalogue totally convincing. Using the Warner remaster of 2014 for comparison, I found the sound altogether warmer and much more comfortable to listen to, closer in fact to how I remember the LPs that I used to own (a German EMI Electrola issue, bought as an import). The Warner is perhaps slightly clearer, but the digitalisation tends to add glare to Callas’s top register. Often one is prepared to flinch before the topmost notes, but I had no such problems when listening to this Pristine pressing. I couldn’t say which is the more truthful, but I can say that the Pristine is much more comfortable to listen to and this, in turn, affected my impressions of the set, a recording I have known since my youth and was in fact my introduction to the opera.

Lucia was one of the cornerstones of her repertoire, and she first sang it in 1952 in Mexico. The following year she sang the role again in Florence, where she made her first recording of the role under Serafin. It was also the first recording she made for EMI. Back in those days, the opera wasn’t taken very seriously and was most likely considered a silly Italian opera in which a doll-like coloratura soprano ran around the stage showing off her high notes and flexibility. Callas returned a proper tragic dimension to the role, that most hadn’t even suspected was there. There is a touching story of Toti Dal Monti, an erstwhile famous Lucia herself, visiting Callas in her dressing room after a performance of the opera with tears running down her face and confessing she had sung the role for years with no idea of its dramatic potential.

When Callas first sang Lucia in Mexico and recorded it in Florence, she was at the peak of her vocal plenitude, as she was when she first sang it under Karajan at La Scala in 1954, but by the time she sang the role in Berlin in 1955 post weight loss, when Karajan took the La Scala company there, her voice had started to lighten and her conception of the role had become more inward. We can hear this in the famous live recording of one of the Berlin performances, but, for this 1959 recording, she appears to have taken this approach one step further. This may have had something to do with her by now fading vocal resources, but it results in a particularly touching portrayal of the innocent, young, impressionable girl. She has also trimmed away some of the showier variations in the cadenza in the Mad Scene, and the decorations are in consequence somewhat more modest. Am I alone in preferring it sung this way? Personally, I’d prefer to do without all that duetting with the flute altogether, as happens in the complete recording of the opera with Caballé and when Sylvia Sass sings it on one of her recital records. In any case, apart from a few of Callas’s topmost notes, she is in remarkably good voice and the filigree of the role is brilliantly executed with fluid and elegant ease. All in all, I prefer her performance in this set to the one on the 1953 Florence studio recording, not least because of the improved Pristine sound picture.

However, when it comes to her colleagues on this set, I am a little less well disposed towards them than Göran Forsling in his review of the digital download. Ferrucio Tagliavini was 45 at the time of this recording, but he sounds much older, more like an elderly roué than the Byronic Romantic figure of Scott’s and Donizetti’s imaginings. No amount of elegant phrasing can make up for his lack of sheer physical passion and I find myself longing for Di Stefano’s youthful ardour. As for Cappuccilli, he was at the very beginning of his considerable career, and he has yet to find a way of creating character in pure sound. He is just rather dull and no match for Gobbi on the earlier recording or for Panerai in Berlin. Bernard Ladysz makes very little impression at all and both Rafaele Arie and Nicola Zaccaria are preferable.

Serafin, as always, though he may not make any startling revelations, shapes the score with a perfect sense of its dramatic shape, albeit with the cuts that were traditional at the time. Karajan opened up some of those in his performances, and I would still place the 1955 Berlin performance at the top of all Callas’s recorded Lucias, especially in Divina Records latest remastering, but I enjoyed re-visiting this set and I have a feeling I’ll be reaching for this one more regularly than the earlier 1953 recording, not least because of the superior quality of Pristine’s remastering.

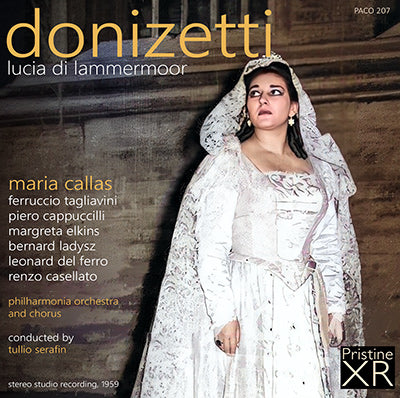

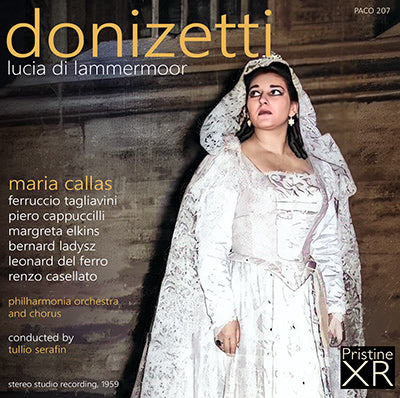

My only criticism is of the cover art, which has a photograph of Callas as Lucia in Florence in 1953, when she was still a rather large lady. One could be forgiven for thinking, at first glance, that this was the earlier recording. Surely a photo of the svelte Callas as Lucia would have been more appropriate. There are plenty of them, after all.