La principessa Turandot – Birgit Nilsson (soprano)

Calaf – Franco Corelli (tenor)

Liù – Licia Albanese (soprano)

Ping – Frank Guarrera (baritone)

Pang – Robert Nagy (tenor)

Pong – Charles Anthony (tenor)

Timur: Ezio Flagello (bass)

L’imperatore Altoum – Alessio De Paolis (tenor)

Un mandarino – Calvin Marsh (baritone)

Chorus and Orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera/Kurt Adler

rec. live radio broadcast, 24 February 1962, Metropolitan Opera House, New York City, USA

Well, let’s get this straight. This is an exciting performance of Puccini’s last opera, which puts you in a good seat at the old Metropolitan Opera House on a night when two of its greatest stars were singing two of their greatest roles. You can sense the excitement in the house from the moment the radio announcer, Milton Cross, introduces the opera with the words, “We’ll have the loud, crashing chords, then the curtain will open on the walls of the oriental Imperial palace of Peking.” Indeed the set is loudly applauded by the audience.

After the excitement of those opening chords and the chorus which follows, it is something of a disappointment to be confronted with the Liu of Licia Albanese, who was approaching 53, but quite frankly sounds even older. She compensates by loudly over-singing and over-emoting, and I derived very little pleasure from her performance. Her days at the Met were evidently numbered and she left the company in 1966, following a dispute with Sir Rudolf Bing.

For the rest, we have a sonorous Timur from Ezio Flagello, but the Ping, Pang and Pong tend to over-characterise their music and consequently I found their scenes irritating, as I often do.

However, the main reason for hearing this set remains the splendid singing of Nilsson and, especially Corelli. I am not one of those who think Corelli can do no wrong, but in the right role, and Calaf is undoubtedly the right role for him, he is unbeatable. First of all, there is the sheer splendour of that sound, the thrill of his top notes, which he can fine down to almost a whisper in places. He is absolutely thrilling and the audience go wild after Nessun dorma, with Adler abruptly stopping the orchestral postlude until the pandemonium has died down.

So too, of course, is Nilsson, throwing out those top notes like laser beams. The punishing tessitura holds no terrors for her at all and it is all very exciting, if not particularly subtle. Nor is the conducting of Kurt Adler, for that matter, but he certainly knows how to whip up the excitement.

According to Lee Denham in his exhaustive survey of the opera, there are, or have been, available seven other recordings featuring Nilsson, three of them with Corelli, so how necessary is this particular recording? I’m pleased to have heard it, but I’m not sure I’d want it as my one representation of Nilsson and Corelli in the opera. For that, I’d probably stick with the EMI recording under Molinari-Pradelli, which also has the benefit of including the Act III aria Del primo pianto, which is omitted from all Nilsson’s live accounts. It also has the benefit of the young Renata Scotto as Liu.

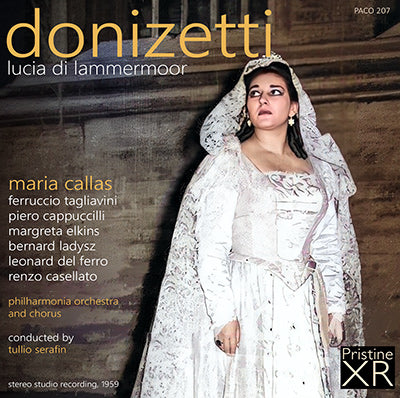

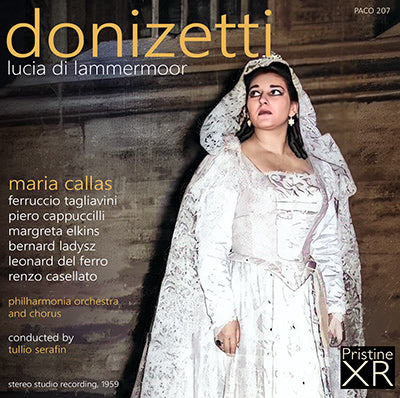

I would also not want to be without the Mehta recording with Sutherland, Pavarotti and Caballé, nor the Serafin with Callas, Fernandi and Schwarzkopf, but this one is a great reminder of a thrilling afternoon at the old Met.