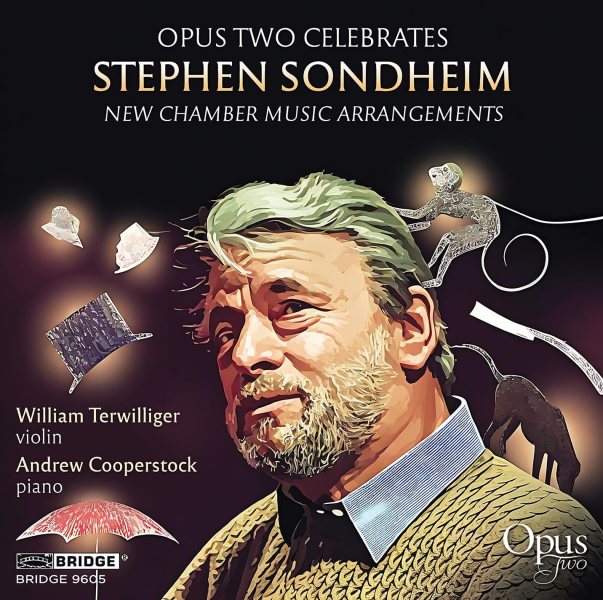

I’ve loved the music of Stephen Sondheim ever since I was introduced to the LP of the Broadway recording of A Little Night Music by an old friend, my musical mentor, back when I was in my early twenties. Though Sondheim is known for his lyrics, it was the swirlingly Romantic score that I first responded to, and it is fitting that the first piece on this disc is the Suite from that musical, in an arrangement, like the other pieces on this disc, by Eric Stern, who worked closely with Sondheim on the 1984 revival of Pacific Overtures. Since then, Stern has conducted the second year of Sunday in the Park with George, and also worked on Into the Woods, several productions of Follies, a revival of Merrily We Roll Along at the Kennedy Centre, and many more concerts and birthday celebrations around the world. His last conversation with Sondheim was about the Little Night Music suite, which Sondheim enthusiastically endorsed, though unfortunately the rest were written after his passing.

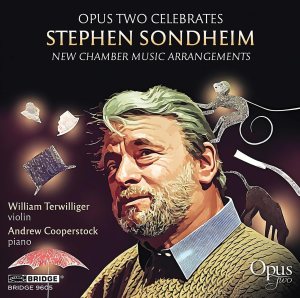

Opus Two are violin and piano duo, William Terwilliger on the violin and Andrew Cooperstock on the piano. They are joined by soprano Elena Shaddow for I remember, from the TV musical Evening Primrose, and by baritone Andrew Garland for Finishing the Hat, from Sunday in the Park with George, though, truth to tell, neither performance eclipsed memories of other performances of these songs, and I wondered at their inclusion. On the other hand, the addition of Beth Vandeborgh’s cello to the arrangement of Every Day a Little Death from A Little Night Music adds a certain expressive depth to the song. I found it one of the most successful pieces on the disc.

For those who know and love Sondheim’s scores, I would suggest that this disc is self-recommending. The arrangements are brilliantly done, though there is just the whiff of Palm Court about them. I could imagine them being played at the Waldorf Hotel, whilst enjoying tea, not that there is anything wrong with that, of course, and I found the disc hugely enjoyable. In some cases, I know the lyrics so well I could sing along in my mind’s ear, which no doubt added to my enjoyment of them.

It has often been said that Sondheim’s lyrics take precedence over the music, but here, I think, we get the chance to concentrate on Sondheim the composer, and we find how lyrical, in the musical sense, his music is. The only piece I didn’t know was the main title from Alain Resnais’s 1974 film, Stavisky, a short evocative piece, but it too has a tune which lingers in the memory for some time afterwards.

Terwilliger shines in Sorry/Grateful from Company, which is here arranged for solo violin, whilst Cooperstock is given the jazzy Now You Know from Merrily We Roll Along as a piano solo. Then they come together again for the final work, the Fleet Street Suite, which combines themes from Sweeney Todd and closes the recital with the beautifully poetic Johanna, which, in the show, is a moment of calm and pure beauty amidst the turbulence of the rest.

Contents:

Suite from A little Night Music

Not while I’m around (from Sweeney Todd)

Broadway Baby (from Follies)

I remember (from Evening Primrose)

Main Title from Stavisky

Every Day a Little Death (from A little Night Music)

Sorry/Grateful (from Company)

Finishing the Hat (from Sunday in the Park with George)

Now You Know (from Merrily We Roll Along)

Fleet Street Suite (from Sweeney Todd)