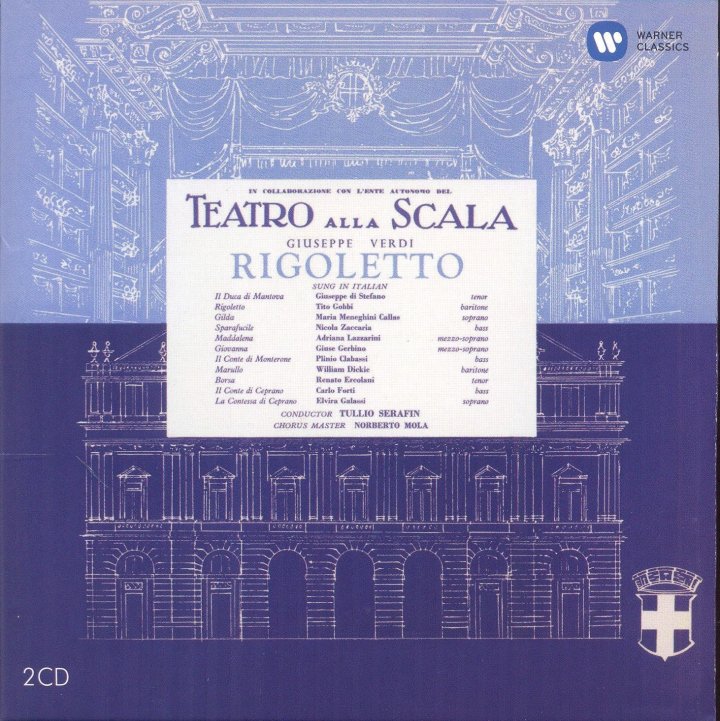

Recorded 24-30 March 1953, Basilica di Sant’Eufemia Milan

Producer: Dino Olivieri, Balance Engineer: Osvaldo Varesca

I Puritani, Callas’s second opera for EMI was the first recorded under the imprimatur of La Scala, an association which would result in eighteen further opera sets over a period of seven years.

No doubt because of the circumstances surrounding her first Elvira (she learned it in 3 days to replace an ailing Margherita Carosio whilst still singing Brunnhilde in Die Walkure) and because of her famed recording of the Mad Scene, one would expect the role to have played a greater part in her career, but in fact after those first performances in Venice in 1949, it figured rarely in her repertoire.

She sang it again in Florence, in Rome and in Mexico in 1952, and in her second season in Chicago in 1955, then never again, though the Mad Scene did occasionally appear in her concert programmes, even as late as 1958 at a Covent Garden Gala. A recording of her rehearsing the scene for her Dallas inaugural concert in 1957 exists, and shows her still singing an easy, secure and full-throated high Eb.

Maybe the reason she sang it so little is that Elvira offers less dramatic meat than Lucia or even Amina. The libretto is something of a muddle and Elvira seems to spend the opera drifting in and out of madness. Of course she gets some wonderful music to sing, and Callas certainly breathes a lot more life into her than most singers are able to do. She also gives us some of her best work on disc, her voice wonderfully limpid and responsive, the top register free and open. No doubt this is the reason it has remained one of the top choices for the opera since its release over 6o years ago.

We first hear her in the offstage prayer in Act I Scene I, and straight away there is that thrill of recognition as her voice dominates the ensemble. Then in the scene with Giorgio, she finds a wide range of colour, a weight of character, that we don’t normally hear. Her voice, laden with sadness for her first utterances, then defiant when she thinks she is to be wed to someone she doesn’t love, is fused with utter joy when she realises that it is Arturo she is going to marry. She skips through the florid writing with lightness and ease, but invests it with a significance that eludes most others. One moment that stood out in relief for me was her cry of Ah padre mio when Arturo arrives, which bespeaks the fullness of heart that is the main characteristic of this Elvira. Son vergin vezzosa is a miracle of lightness and grace, Ah vieni al tempio heartbreakingly real, though her voice does turn a little harsh when she doubles the orchestral line an octave up.

The Mad Scene needs little introduction. It is one of the most well-known examples of her art out there, the cavatina moulded on a seemingly endless breath; and where have you ever heard such scales in the cabaletta? Like the sighs of a dying soul. The top Eb at its climax is one of the most stunning notes even Callas ever committed to disc, held ringingly and freely without a hint of strain. Words fail me.

She has less to do in the last act, which mostly belongs to the tenor, and this is where I have a problem with the set. Di Stefano is nowhere near stylish enough in a role that was written for the great Rubini, and he lurches at every top note as if his life depended on it. Sometimes the notes sound reasonably free, at others he almost sounds as if he’s holding onto them with his teeth. Mind you, who else was there around to sing it any better at that time? The recording was made too early for Kraus, though Gedda might have been a good idea. After all, he was already singing for EMI by then, and would sing Narciso on Callas’s recording of Il Turco in Italia, which was recorded the following year..

Rossi-Lemeni is less woolly-toned than I remember him and sings with authority, especially good in the first act duet with Callas; Panerai is a virile presence as Riccardo. Serafin conducts with his usual sense of style, but also invests some drama into the proceedings.

The orchestra and voices sound really good, but the recording of the chorus is a bit muddy. Presumably that was also the case on the original LPs.

I do have a few problems with I Puritani. To my mind the libretto is plain silly, and even Callas’s wonderful singing can’t quite rescue it. That said, as singing qua singing, it’s some of the most amazing work she ever committed to disc, and for that reason it will always be a permanent part of gramophone history. I would never be without it.