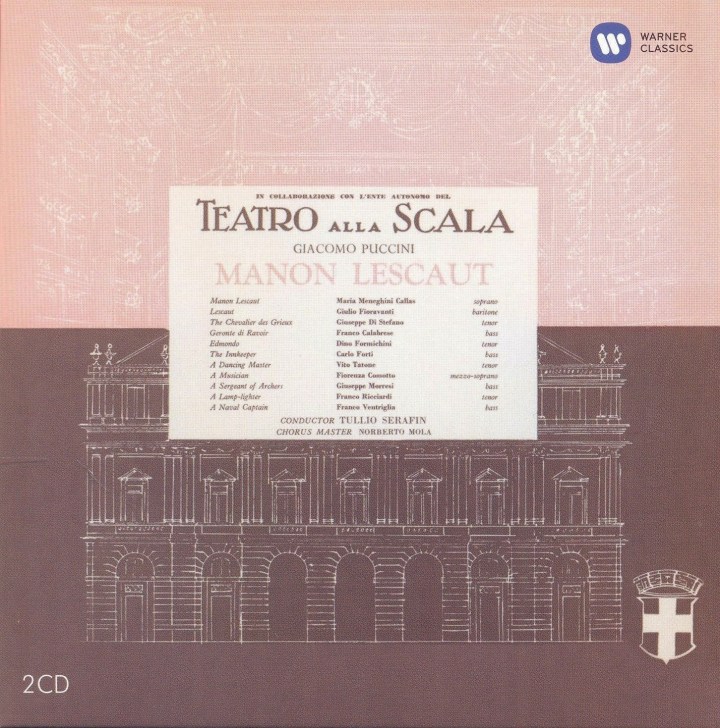

Recorded 18-27 July 1957, Teatro alla Scala, Milan

Producer: Walter Legge, Balance Engineer: Robert Beckett

Manon Lescaut has never been a favourite opera of mine, and to my mind pales in comparison to Massenet’s work, which is a truer representation of L’Abbe Prevost’s novel, for all that he ends the opera in Le Havre rather than America; nor does this recording rank particularly high in my roll call of Callas recordings. Though recorded in 1957, it waited 3 years before it was released, so presumably Legge and Callas had their doubts too.

For much of the first two acts, the recording itself has a curiously flat sound to it, and though we hear a fair amount of orchestral detail, both strings and voices sound undernourished. I don’t know whether it was me becoming more involved, but things do seem to improve in the last two acts, where Callas also sounds more comfortable vocally.

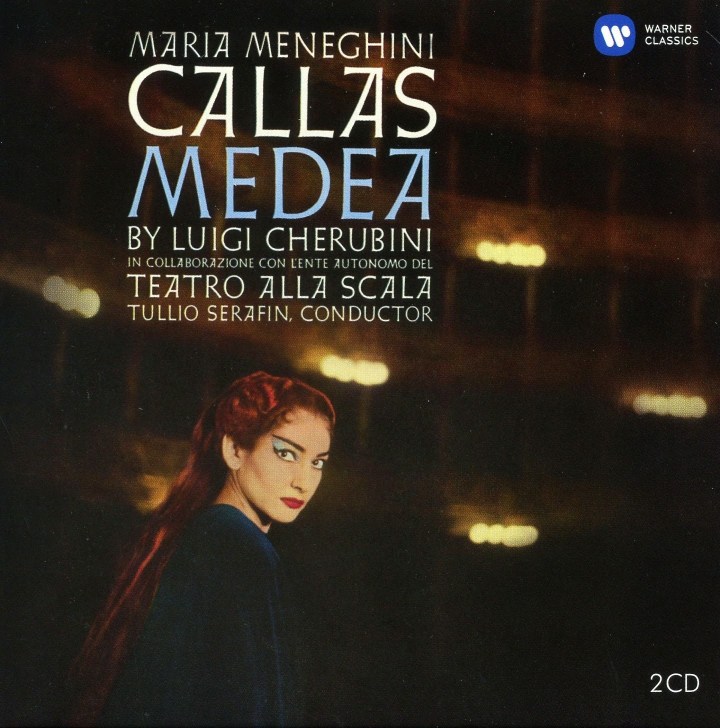

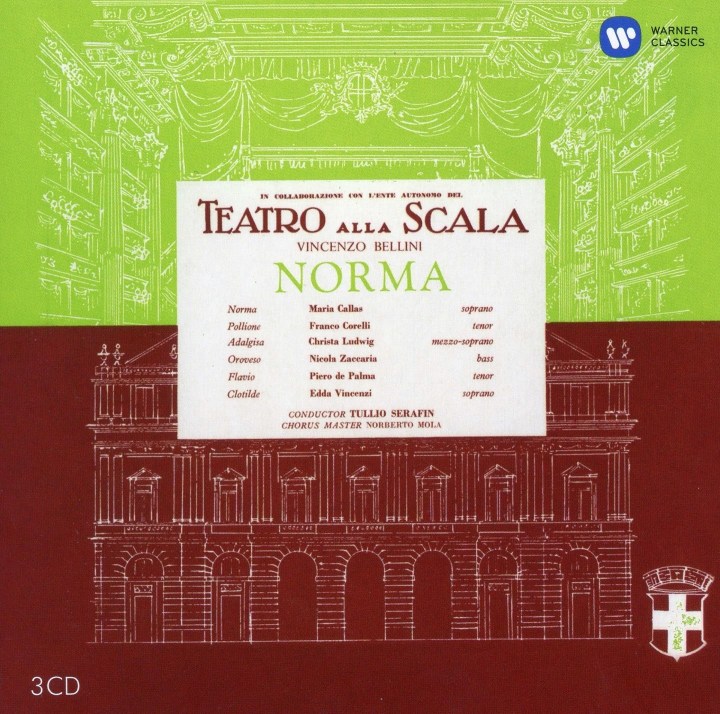

To my ears, she has always sounded utterly exhausted in this set. It was recorded shortly after Turandot, which she really ought not to have been singing at that stage in her career anyway. She manages Turandot surprisingly well, but the effort it must have cost her shows in the parlous state of her top in much of this Manon Lescaut. She is actually in much better voice in the later complete recordings of La Gioconda, Lucia di Lammermoor and Norma, even the Medea, which followed it, but then in all those she was singing repertoire more suited to her gifts. I’m not sure it was ever the right voice for Puccini, for all her success in the role of Tosca. Not long after this, she sang Amina in Edinburgh and made the studio recording of Medea, neither of which find her in her best form, and it is not until the Dallas Inaugural Recital in November that she recovers form. She is also in stupendous voice for the live La Scala Un Ballo in Maschera in December, so presumably she had benefited from some rest. Even in the middle and lower registers here, much of the velvet is missing from the voice, and even in quieter passages she doesn’t seem to have sufficient energy to support the voice.

Of course, there are, as always, musical compensations aplenty. In the first act, Callas sings with a lightness and purity that mirrors Puccini’s con semplicita markings. Later, her In quelle trine morbide is even more finely nuanced than on the recital disc of 1954, sung more as a reflection to herself than to Lescaut; and the trills and grace notes in L’ora o Tirsi are sung with a lightness and accuracy that eludes most singers of the role; the duet with Des Grieux is full of restrained passion. In Act III she has less to do, but her few exchanges have a weariness and dull despair that is most affecting. However it is in the often anti-climactic final act, where vocally and dramatically she is at her best, with a harrowing Sola perduta and a chillingly moving death scene.

Di Stefano’s singing is variable, occasionally disturbingly tight on top and at other times admirably free, but he does bring personality and face to his singing. Full of youthful joie de vivre in Act I, he becomes a man consumed with love and literally at the end of his tether for Guardate, pazzo son. It’s an appreciable performance, if not the best sung Des Grieux you’ll ever here.

No complaints about the rest of the cast. Fioravanti I have never come across before or since, but he makes an excellent Lescaut and we also get a nice cameo from Fiorenza Cossotto as the madrigal singer.

Serafin, as so often, gets the pacing just right. So much about his conducting is just so unobtrusively right, and in Act III he builds the ensemble leading up to Des Grieux’s outpouring at Guardate, pazzo son in masterly fashion.

Not an opera or a recording that I want to listen to that often, (why oh why didn’t Legge record her in more of the repertoire for which she became famous?) but it certainly has its moments.