Issued to mark the one hundredth anniversary of Schwarzkopf’s birth in 2015, this fantastic 31 disc set brings together all the recital discs Schwarzkopf made in the LP age with her husband Walter Legge between the years 1952 and 1974, adding the live 1953 Wolf recital from Salzburg, with Furtwängler and the farewell to Gerlald Moore at the Royal Festival Hall in 1967, in which she shares the platform with Victoria De Los Angeles and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. It is a considerable achievement, covering operatic excerpts and a huge range of Lieder and song, both with orchestra and piano. It is not quite the full story, for their was to be one further recital to come, made for Decca in 1977 and 1979, and simply called To My Friends.

Schwarzkopf started out as a coloratura, singing roles such as Zerbinetta, Blonde and Sophie, but the voice was never entirely comfortable in the stratospheres, and she soon graduated from Sophie to the Marschallin, from Susanna to the Countess. A serious and dedicated artist, over the years she wittled down her operatic roles to a mere five (Mozart’s Countess, Donna Elvira and Fiordiligi and Strauss’s Marschallin and Countess Madeleine) so that she could concentrate on her recital work, which was her first love. The voice was not particularly large, but a warm, lyric soprano, shot through with laughter, her technique faultless and, though it lost something of its bloom in later years, it was always firm and true with no trace of excessive vibrato or wobble. She has been saddled for many years with the adjective ‘mannered’, but, listening to these CDs now, what I hear is incredible intelligence and specificity, a voice put at the service of the composer, not the other way round. People love to make fun of the fact that, when invited onto Desert Island Discs she picked all her own records, but, if you listen to the porgramme now, she uses them as illustrations of key points in her life. She was actually severely self-critical and those few records represented the best of herself and her collaborators, for she was quick to give credit to the conductors and accompanists she had worked with, and of course to her husband Walter Legge, who produced all her records. John Steane, who loved Schwarzkopf unreservedly, spent some time listening with her to her records in her retirement, and was surprised at how rarely a recording got her full stamp of approval. Listening sessions were interrupted by continuous cries of “too much of this, too little of that. Intonation, missy” and so on, and just the occasional “ah yes, missy, that’s good”. In other words she was as hard on herself as she famously was on her students, who could find working with her frustrating, as she barely let them get a few bars out; but this was the only way she knew how to work herself, and what do teachers do other than pass on their experience to others?

There is a lot of music to get through here, though most of the CDs are rather short in length, being exact reissues of the LPs as they appeared, each in its own sleeve with the original artwork. The only cause for regret has nothing to do with the music or the music making, but with the fact that no texts and translations are included. This is a criminal omission with an artist like Scwharzkopf, who paid such attention to the words, colouring her voice to get the maximum amount of meaning from them. These days it should be easy to produce a weblink or CD-Rom with them all, and I’m guessing that most collectors wouldn’t mind paying a little extra just to have them. As it is, I am having to hang on to all my previous issuse of this material, simply to keep the texts.

So on to the actual discs and a potted review of each one.

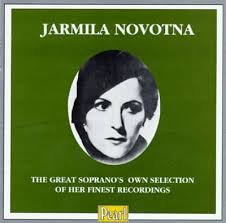

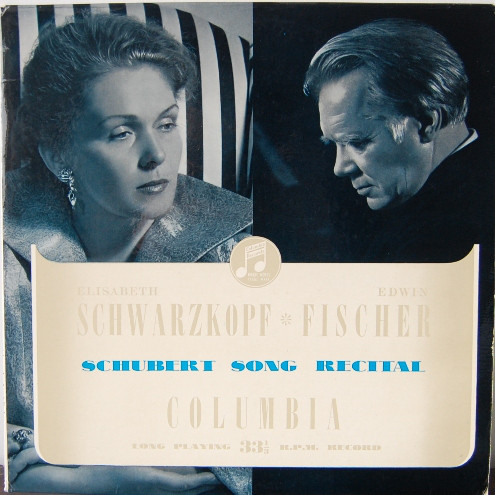

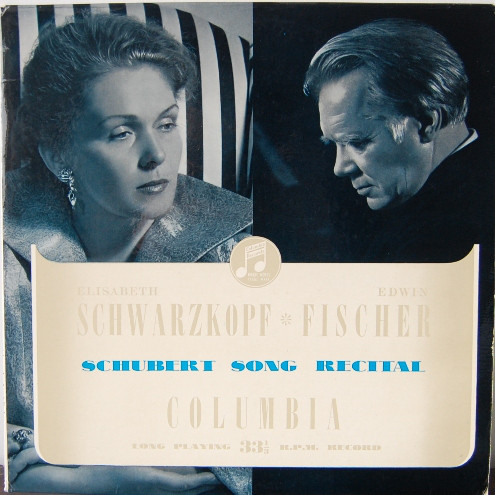

Disc I. Schubert Song Recital with Edwin Fischer

This is a classic recital, with Schwarzkopf’s voice at its freshest and loveliest, the lighter songs delivered with a delightful smile in the voice, the darker ones with an arresting sense of their dramatic potential. For instance, in Gretchen am Spinnrade the words sein Kuss are sung almost in horror, as Gretchen recalls the moment which sealed her destiny. Though always alert to the mood and meaning of the songs, however, there is also much that is admirable as pure singing, the legato superb, the line firmly held. Fischer is an estimable partner rather than just an accompanist. I particularly love the way he makes the piano accomaniment in Auf dem Wasser zu singen conjure up the image of moonlight bouncing off the water. A delight from beginning to end.

Disc 2. Mozart Operatic Arias

Here accompanied by the Philharmonia Orchestra under John Pritchard (no Sir back then), Schwarzkopf sings a collection of arias from roles she did sang on stage as well as some she didn’t. Not many sopranos would attempt in the same recital arias for the Countess, Susanna and Cherubino or for Zerlina and Donna Anna, but, rare in Mozart, she brings a different voice character to each, all boyish eagerness as Cherubino, sensuous charm as Susanna, girlish seduction as Zerlina, who in turn sounds quite different from her Susanna, and patrician elegance as the Countess. Her Donna Anna is not quite so successful, and of course we are reminded that her stage role was that of Donna Elvira, a role which she made very much her own, but Non mi dir is nonetheless delivered with a resigned sadness and the closing coloratura section rings out with real conviction. Illia’s Zeffiretti lusinghieri is altogether lovely.

Disc 3. Strauss Four Last Songs and Capriccio Closing Scene

Through her two recordings , Schwarzkopf has always been associated with Strauss’s ever popular Vier letzte Lieder, though very few people can agree on which of the two recordings is the better. I tend to prefer the later one with Szell, both for the improved sound picture and Schwarzkopf’s more mature thoughts on the work, but both are superb, and this one benefits from her greater ease in the upper register. The closing scene from Capriccio, made before she had recorded the full opera under Sawallisch, is lovely in every way with the character superbly delineated and the voice soaring out over the orchestra.

Disc 4. Strauss – Scenes from Arabella

Staying with Strauss, these excerpts were recorded in 1954 and it always seems a pity to me that Legge didn’t record the whole opera. That said, the opera has its longeurs, for me anyway, and perhaps this is all that I really need. Schwarzkopf is perfectly cast as Arabella and is well contrasted with Annie Felbermeyer, who plays Zdenka here. Josef Metternich is a superb Mandryka, none better on disc, and the cast is fleshed out with such names as Nicolai Gedda as Matteo, Walter Berry as Lamoral and Murray Dickie as Elemer. Lovro von Matacic is much more in tune with Strauss’s medium than Solti on the roughly contemporaneous set with Lisa Della Casa, and, who knows, if this had been recorded complete, it may well have become the touchstone recording for all time.

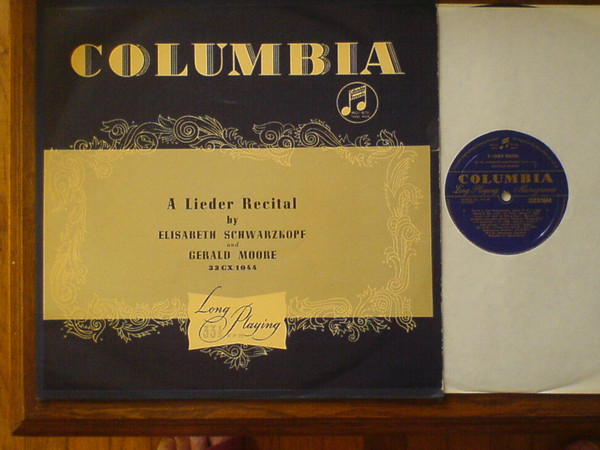

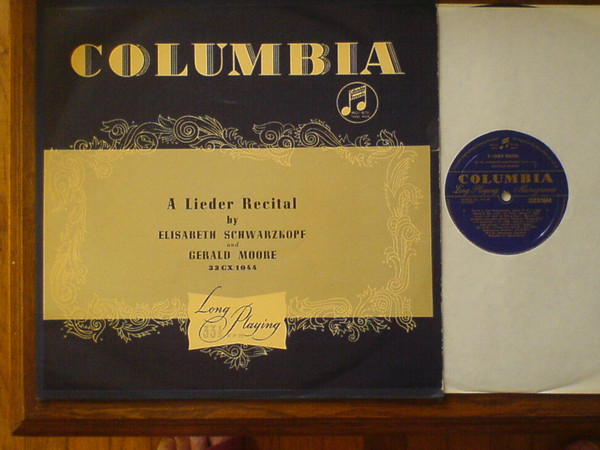

Disc 5. A Lieder Recital

Schwarzkopf returned to Lieder with piano for her next record, a mixed recital with Gerald Moore at the piano. It opens with Bist du bei mir (once attributed to Bach), and continues with mostly popular fare by Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Wolf and Strauss, with Schwarzkopf unerringly catching the mood of each song, whether it be the joyfully youthful exuberance of Schubert’s Ungeduld, or the wistful bliss of Schumann’s Der Nussbaum.

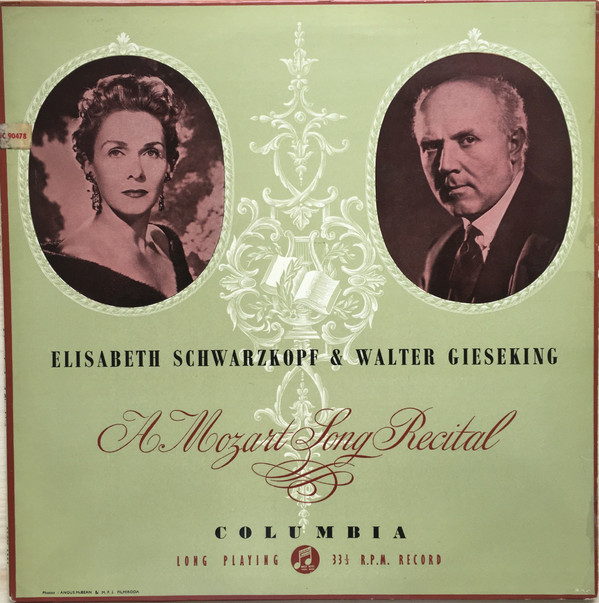

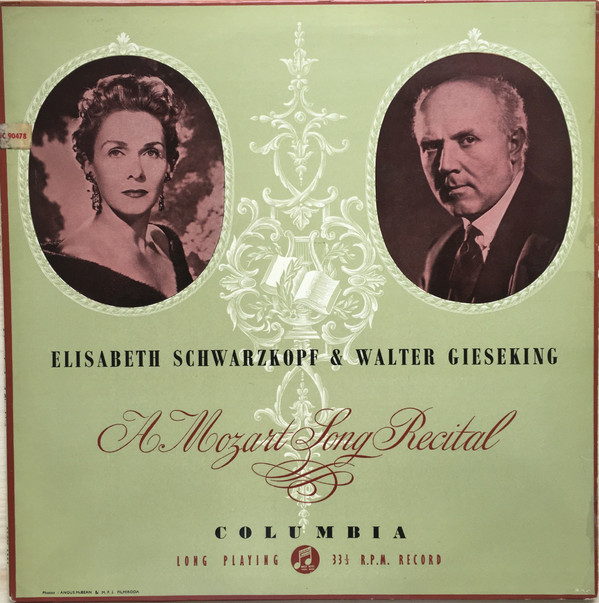

Disc 6. A Mozart Song Recital

This Mozart recital with the great Walter Gieseking at the piano has deservedly achieved the classic status of the Schwarzkopf/Fischer Schubert recital. Recorded in 1955, it was recorded in stereo, and I put this down to the fact that Christopher Parker, who oversaw the stereo version of Der Rosenkavalier was the balance engineer. It was first issued in mono, and the stereo version emerged several years later.

It certainly deserves its classic status, as Schwarzkopf and Gieseking between them bring these simple songs to life as no other. I hear absolutely no artifice in the way Schwarzkopf characterises the songs, or in the way Gieseking mirrors his playing to her tone, making much more of the sometimes plain accompaniments than you would think was possible. They also manage to vary the approach to individual verses in strophic songs in a way which sounds completely natural. This is a wonderful disc.

Disc 7. A Recital of Duets by Monteverdi, Carissimi and Dvorak.

Okay, so the Monteverdi and Carissimi duets are hardly authentic, but I can’t imagine anyone other than the most ascetic HIP advocate complaining when the singing is so beautiful, the voices charmingly intertwining and blending in delicious pleasure.

Schwarzkopf and Seefried had sung together on many occasions, and had already made duet recordings of the Presentation of the Silver Rose from Der Rosenkavalier (Schwarzkopf as Sophie, Seefried as Octavian) and excerpts from Hänsel und Gretel. Schwarzkopf was a huge admirer of Seefried, at one time stating that Seefried had naturally what others, including herself, had to work hard to achieve. Seefried’s slightly darker, more mezzoish timbre blended perfectly with Schwarzkopf’s brighter tone. The result is a winning combination, not only in the Dvorak duets that you would expect would suit them, but in the baroque items too, with Gerald Moore providing alert, lively support on the piano.

Disc 8. Walton – Scenes from Troilus and Cressida

Walton didn’t have much luck with casting for his opera Troilus and Cressida. He had originally wanted Callas for the role of Cressida, but Callas had no interest in contemporary opera and so he offered the role to Schwarzkopf, who was slated to sing in the UK premiere, but she too decided against it, and the role finally went to the Hungarian Magda Laszlo, who spoke no English at all. Scwharzkopf did however record these excerpts with Richard Lewis, the Troilus of the original production, a few months after its premiere.

It is a great pity that she decided not to sing the role, for she fills its soaringly lyrical vocal line with glorious refulgent tone. Her English is clear, if slightly accented, and the recording is a fine memento of what might have been.

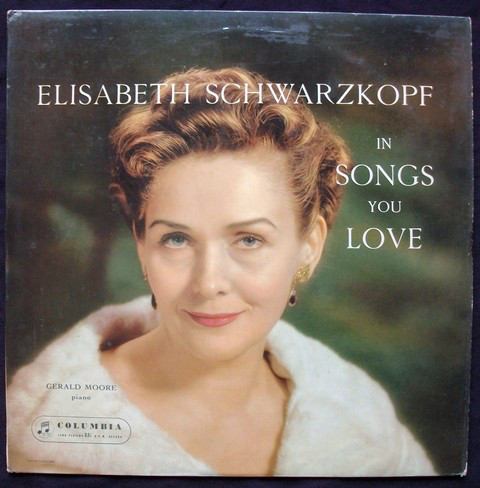

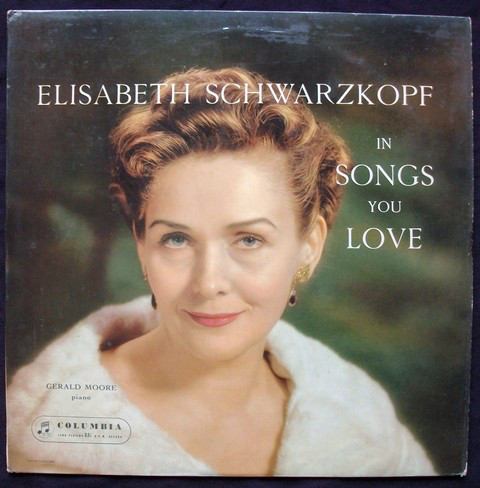

Disc 9. Songs You Love

This 1956 recital is a collection of popular songs of the type that might normally crop up as encores in a recital programme, starting with Quilter’s arrangement of Drink to me only with thine eyes, and continuing with pops by Hahn, Dvorak, Tchaikovsky and Grieg, all much more well known back then than they are now, no doubt. Singing in English, French and German, Schwarzkopf brings as much care to them as she does to the Lieder of Wolf. A lovely disc.

Disc 10. More Songs You Love

This disc turns out to be the one more commonly known as The Elisabeth Schwarzkopf Christmas Album. This time she is accompanied by the Ambrosian Singers and the Philharmonia Orchestra under Sir Charles Mackerras in often gorgeously over the top arrangements of traditional Chiristmas carols and songs, though the disc starts gently with the original arrangement of Gruber’s popular Stille Nacht, on which Schwarzkopf is double tracked to duet with herself. Some might find it all a bit too sugary, but I love it and it has been a permanent part of my Christmas playlist for many years now.

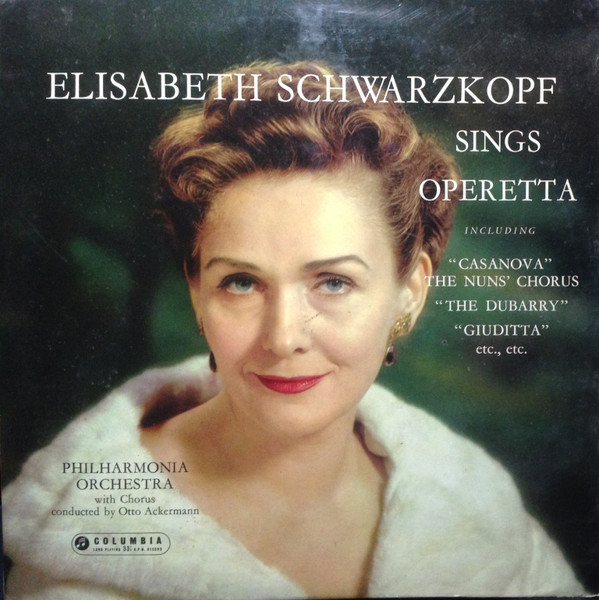

Disc 11. Elisabeth Schwarzkopf Sings Operetta

And so to one of the first Schwarzkopf discs I owned, arguably the greatest disc of operetta arias ever recorded, and pure unalloyed joy from beginning to end. Schwarzkopf may have been born in what is now part of Poland and brought up in Germany, but there is something absolutely echt Viennese about her singing of operetta, and her recordings of operettas by Strauss and Lehár remain touchstones against which all others are judged. Schwarzkopf makes no concessions to the material and sings with her customary attention to detail, but there is absolutely no suspician of artifice or over-inflection and the disc is guaranteed to lift the spirits of all but the most curmudgeonly.

Disc 12, 13 & 14. Hugo Wolf – Goethe Lieder, From the Italian Song Book, From the Romantic Poets

Schwarzkopf followed three discs of lighter fare with three discs of Wolf Lieder. The discs are quite short and all the material was reissued at one time on a two disc set in EMI’s Great Recordings of the Century series, and deservedly so. I would urge anyone who gets the present box set to also acquire the GRC release, as that comes with fuill notes, texts and translations, absolutely essential when listening to Wolf, especially in performances as finely nuanced and detailed as these. Schwarzkopf’s name, along with that of Fischer-Dieskau, has been indelibly associated with the songs of Hugo Wolf, and they, more than any other singers, were responsible for bringing Wolf’s name to prominence after the Second World War.

Schwarzkopf’s ability to sing with a sparkling eye and a smile in the voice is particularly suited to Wolf’s lighter songs, but she also has the pathos for the Mignon songs, and her yearningly intense performance of Kennst du das Land is arguably the greatest performance of a Wolf song committed to disc. At almost seven minutes it is the longest song on these three discs, and Schwarzkopf and Gerald Moore build the intensity in masterly fashion, using every colour at her disposal to convey every shade of meaning. Some might say that this attention to detail robs the performances of spontaneity, but I’d disagree. Though obviously thoroughly worked out in rehearsal, Schwarzkopf still experiences the song as it happens. Never have the words “mannered” and “arty” been so off the mark. Would that more singers today could sing with such attention to detail.

Disc 15. Schwarzkopf portrays Romantic Heroines

Schwarzkopf sang Elsa at La Scala in 1953, but it didn’t appear much in her repertoire after that. These two excerpts from Lohengrin are quite superb, the duet with Christa Ludwig’s Ortrud (well known from the complete Kempe recording) absolutely thrilling. Elsa is sung on that recording by the wonderful Elisabeth Grümmer, and there can be higher praise than stating Schwarzkopf is her equal in every way. She makes a superb Elisabeth too, greeting the Hall of Song in joyful radiance, sincerely sorrowful in the prayer, the tone pure and ideally floated. The arias from Der Freischütz are also qukte wonderful and have a beauty and poise rarely achieved by others. This is a glorious disc, one of Schwarzkopf’s very best..

Disc 16. Favourite Scenes and Arias

Though Schwarzkopf sang Mimi early in her career, she didn’t sing any of the other roles featured on this disc. We don’t really associate her with Italian opera, though she made two excellent recordings of the Verdi Requiem and was an infectiously high spirited Alice in Falstaff. She might have made an excellent Desdemona too, if this scene is anything to go by, floating the tone ideally in the Ave Maria and alive to Desdemona’s anxiety and foreboding in the Willow Song. Her Lauretta is all youthful charm and her Mimi lovely in every way. The Smetana and Tchaikovsky are both sung in German. She is radiant in Marenka’s solo and, if Tatyana’s Letter Scene misses something of the girl’s impetuosity, the slow section has a satisfyingly inward quality.

Disc 17. Strauss – Four Last Songs and Five Other Songs with Orchestra

This is one of the most famous records Schwarzkopf ever made and has remained a best seller ever since its first release. I’ve had it in one form or another since my teens, and, though I’ve listened to countless other versions of the Four Last Songs, and come to love quite a few of them, it is still the one I hear in my mind’s ear whenever I think of Strauss’s great apotheosis to the soprano voice. Schwarzkopf and Szell remind us that these are, after all, Lieder and not merely vocalises. They probe more deeply into the valedictory nature of the songs than any other I know, and the recording has a rich autumnal glow, eminently suited to their approach. In the last song, when Schwarzkopf sings So tief im Abendrot the effect is of a cathartic release, as if the whole cycle had been leading up to that moment. I don’t hear that in any other performance, and for this reason, Schwarzkopf/Szell still, for me, eclipse all competition. The other five songs are hardly less fine. A desert island disc if ever there were one.

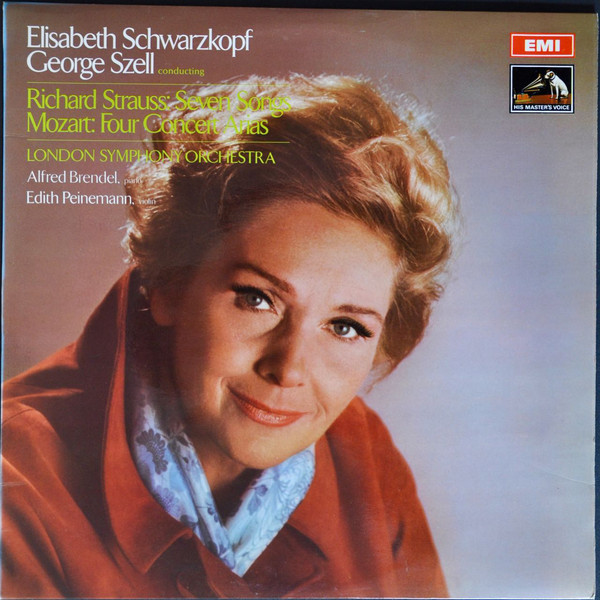

Disc 18. Concert Arias and Lieder

No doubt the success of their Berlin recording of the Four Last Songs prompted Szell to take Schwarzkopf and Szell back into the studio, this time in London with the London Symphony Orchestra. The first side of the LP was devoted to Mozart concert arias and the second to Strauss Lieder, the two cornerstones of Schwarzkopf’s work with orchestra. For Ch’io mi scordi di te she is joined by Alfred Brendel for the piano obbligato, the two artists intertwining their voices deliciously in duet, and she brings her familiar virtues of aristocratic phrasing and dramatic involvement to each aria. Schwarzkopf had her misgivings about the Mozart items, feeling that, though they are musicaly fine, the voice had darkened too much for Mozart. Maybe she has a point, but I’ll put up with the less youthful voice for the dramatic insights she brings to them. The Strauss songs are all gorgeous and wonderfully characterised, the turbulence of Ruhe, meine Seele contrasting immediately with the gently lulling tone of Meinem Kinde, and so on. For Morgen, she is joined by Edith Peinemann on the violin.

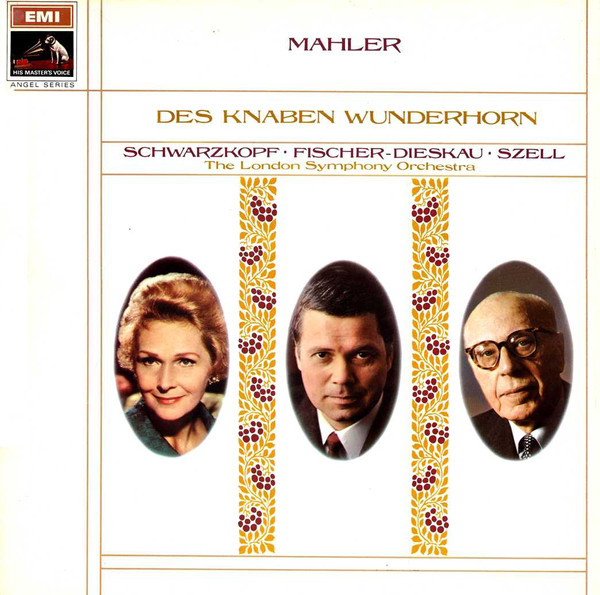

Disc 19. Mahler – Des Knaben Wunderhorn

This was recorded and released before the Mozart/Strauss disc, which made me realise the discs aren’t numbered chronologically. No matter, it has been considered a classic since its release in 1968. Like the Four Last Songs, I’ve owned it since my college days, and it brings back memories of listening in my tiny room in student digs all those years ago. Some feel that the interpretations are too sophisticated for the essential folk-nature of the songs, but I’d argue that Mahler’s wonderful orchestrations, superbly rendered here by Szell and the London Symphony Orchestra, already take them quite a few steps from their folk song roots.

Personally, I marvel at the intelligence, the detail and the sheer beauty of the singing. In comparison others sound just too penny plain. Is it interventionist interpretation? Well, I suppose it depends on how you look at it, but everything these superb artists find is there in the music, if you take the time to look for it. It’s also a real collaboration between all three artists, the duet songs being some of the highlights of the set.

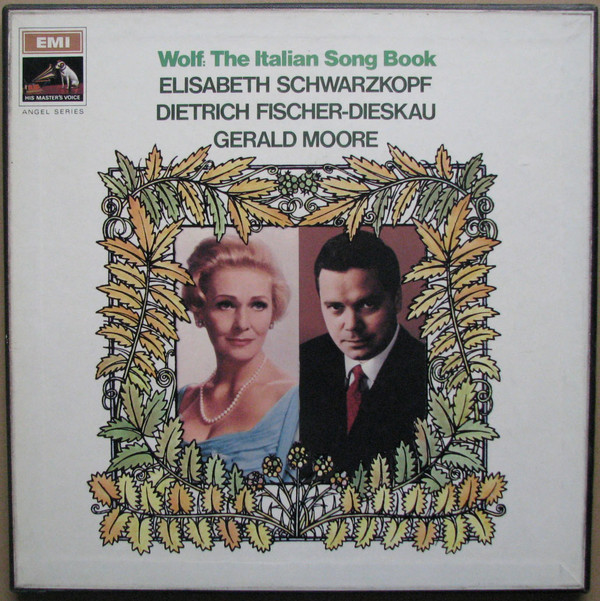

Disc 20. Wolf – Italienisches Liederbuch

This was originally a two disc set, recorded at sessions in Berlin in 1965, 1966 and 1967, Schwarzkopf re-recording all the songs she had recorded back in 1959. With the two foremost Wolf interpeters of the day accompanied by Gerald Moore it is self-recommending, and remains the set by which all others are judged.

The songs are presented in the order they appear in the book, which really is the best way of doing them, and are mined for every shade of meaning by these two great artists, with the inestimable aid of Gerald Moore at the piano.

Discs 21 & 22 – Brahms – Deutsche Volkslieder

Before anyone starts complaining of too much sophistication, one should point out that these are not really folk songs at all. Many were inventions of nineteenth century composers, and, in any case, Brahms’s accompaniments turn them into songs by himself. That said, the songs are probably best listened to piecemeal, rather than at one sitting, when they could be said to outstay their welcome.

Schwarzkopf and Fischer-Dieskau bring their familiar virtues of dramatic involvement and characterisation to the songs, and, though some may find their interventionist approach “mannered”, I prefer it to the somewhat penny plain singing we get from so many interpreters these days.

Discs 23 – 26 The Elisabeth Schwarzkopf Songbook Vols 1 – 4

The first of these discs collected together recordings made in 1957, 1958 and 1962 and was issued in 1966. Presumably the intention was to find a home for performances that had not otherwise found their way onto disc, and no doubt the success of the record prompted Legge and Schwarzkopf to put together three more discs in the same manner. It should be noted that Gerald Moore retired from the public platform in 1967 and, aside from a few tracks that were recorded before then, Geoffrey Parsons is the accompanist on volumes 2-4.

The programmes ranged wide. In addition to the more regularly encountered Schubert, Schumann and Wolf, they take in songs by Mozart, Mahler, Brahms, Strauss and Loewe, Debussy, Chopin and Liszt, Rachmaninov, Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky and Stravinsky, Grieg and Wolf-Ferrari, though the Russian songs are sung in English or German translation.

Disc 27. Songs I Love

Recorded at sessions in 1970 and 1973, with Geoffrey Parsons at the piano, this was, in all but name, another addition to the Songbook series, though this time concentrating on the two cornerstones of Schwarzkopf’s Lieder repertoire, Schubert and Wolf, with the addition of Schumann’s Der Nussbaum, revisiting material that she had recorded before. Though her artistry remains undimmed, we begin to be aware that this is no longer the voice of a young woman. Still there are rewards to be had in hearing how Schwarzkopf’s ideas on certain songs changed over the years, and we note that each new version is a re-thinking of what she had done before. There is never any suspicion of routine.

Disc 28. Schumann – Frauenliebe und Leben & LIederkreis, Op.39

This was Schwarzkopf’s last record for EMI, and she herself had her doubts. Ever the realist and her own strictest critic, she was well aware of the diminution of her vocal powers. In fact, had it not been for Legge urging her on, she would probably have retired sooner. “My voice was on the waning side, and all kinds of muscular powers had gone, and the breathing had gone. You can hear that the voice was getting old, surely. And one doesn’t like that and one tries to make do with all kinds of funny vowels, and oh dear it is really an awful thing.” She was particularly unhappy with Frauenliebe und Leben, which she felt should, in any case, be sung by a mezzo. “I made up by darkening the colour and all sorts of things.”

Of the two cycles, the Liederkreis is the more successful, but no amount of intelligent interpretation can disguise the fact that the voice is not what it was. Her final record was made for Decca a couple of years later, Legge’s rift with EMI being by this time complete. Legge died in 1979, and Schwarzkopf abruptly cancelled all further engagements. Without Legge’s constant encouragement, she was unprepared to continue. “He thought there woud be some moments which would be more memorable. But if you don’t have the voice you cannot put over what you would like to – you make ways round it technically, and by that time it has already vanished.”

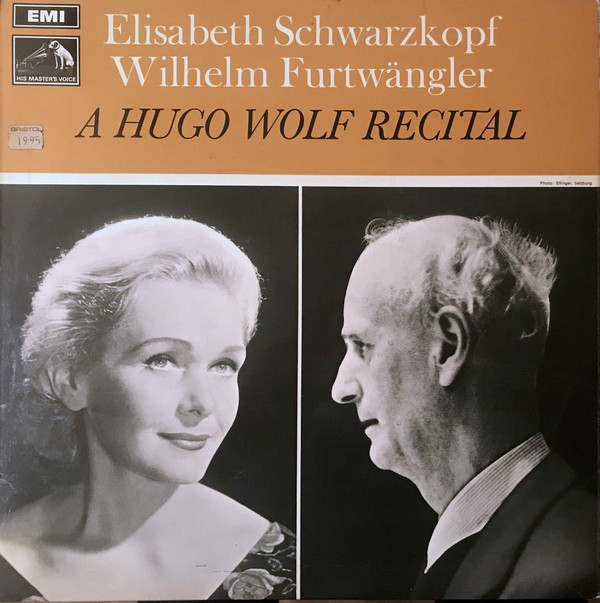

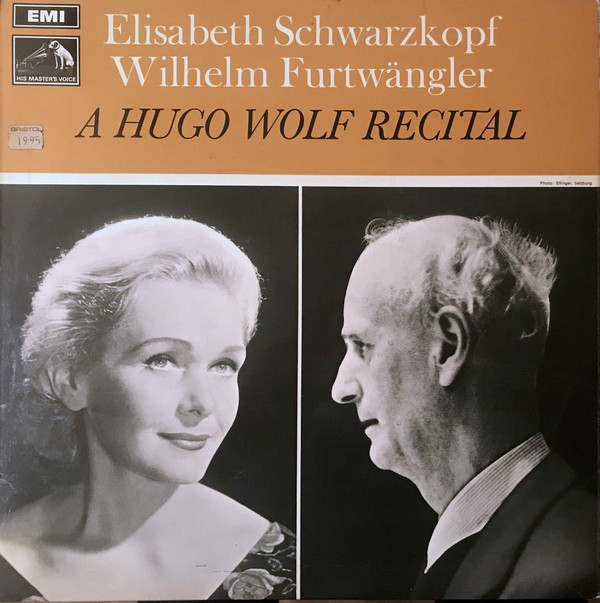

Disc 29. A Hugo Wolf Recital

For Disc 29 we go back almost to the beginning – a recording of a live all Wolf recital given in Salzburg in 1953, which was first released in 1968.

This was quite an occasion and something that Furtwängler himself had suggested. Wolf’s piano parts can be fiendishly difficult, and he apparently practiced hard for the occasion. There are some wrong notes, and some wrong entries here and there, “but it doesn’t matter. Furtwängler accompanying was an event, and so one had to do what one could to make it possibe. It was a service to Wolf, and to music, and a labour of love, that recital. With any other accompanist it matters if he cannot achieve the right tempi, but with Furtwängler it didn’t matter.”

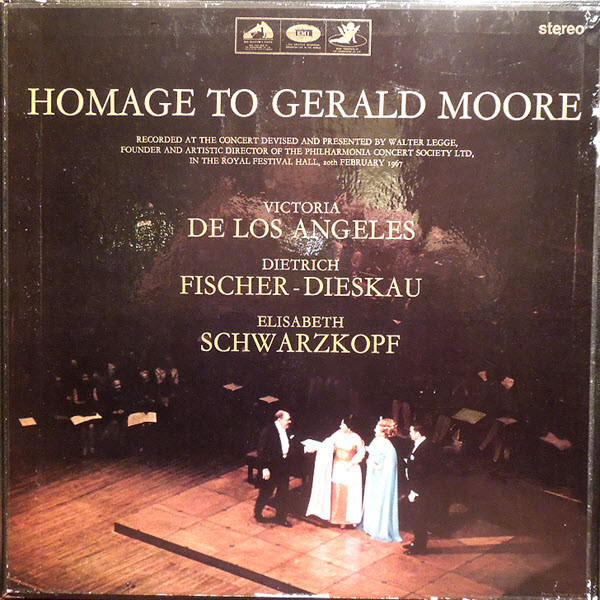

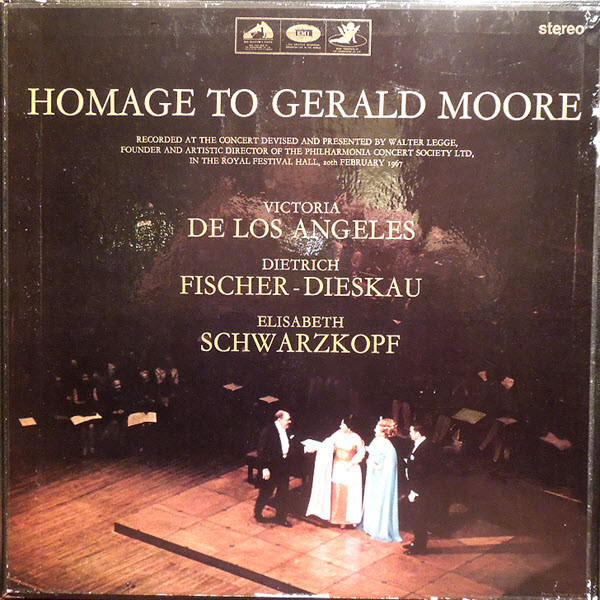

Discs 30 & 31 – Homage to Gerald Moore

The final two discs in the box are given over to the concert in February 1967, at which the musical world, with the aid of his three most regular collaborators, said goodbye to Gerald Moore. There are duets and trios, and each of the singers gets their solo spot, for Fischer-Dieskau a group of Schubert songs, for De Los Angeles a group of Brahms, and for Schwarzkopf, inevitably, a group of Wolf songs, starting with the song she made so much her own, Kennst du das Land. It is a joyous occasion, and the audience evidently enjoyed themselves enormously. It ends with Moore’s own solo arrangement of Schubert’s An die Musik, which is also a fitting end to this whole enterprise. However Warner have tacked on Schwarzkopf’s renditions of Abscheulicher! from Fidelio and Ah, perfido, which originally appeared as fill-ups for Karajan’s Philharmonia set of the Beethoven symphonies. Leonore may not have been a role for Schwarzkopf but her rendition of the big scena is surprisingly successful, the slow section having a wonderful innigkeit. She is immeasurably helped by Dennis Brain’s superb horn playing.

What a joy it has been listening to these thirty-one discs, all of such consistent high quality. The word “mannered” has been overused to describe the art of Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, but, having listened to her almost exclusively over the last few weeks, it seems a long way short of the mark. I hear a singer who characterises, who makes choices based on the music and the text, who is never bland or merely pretty, though she can also make ravishing sounds, and these records represent an incredible achievement by one of the greatest singers of the twentieth century.