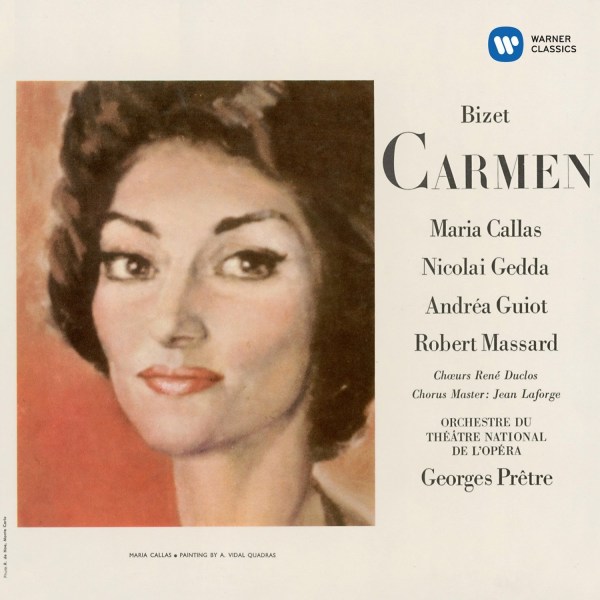

Recorded July 1964, Salle Wagram, Paris

Producer: Michel Glotz, Recording Engineer: Paul Vavaseur

And so, still moving chronologically backwards through this set, we come to the last of the four roles Callas recorded without ever singing them on stage. This Carmen has always been controversial, the most controversial element being Callas herself, so, let me deal with the rest first.

The edition used wouldn’t bear scrutiny. We are of course back in the days of the old Guiraud recitatives, but there’s no point complaining about that. This is how everyone was doing Carmen back then. The sound is excellent early 1960s stereo and sounds better than ever in this new re-master.

This is a very French Carmen. Aside from Callas and Gedda, everyone else involved is French, and Gedda was, in any case, the best “French” tenor around in those days. Pretre’s conducting is swift, sometimes maybe too much so, and deliciously light in places, but his speeds make dramatic sense and it works very well. The orchestra and chorus, again French, sound idiomatically right to me. The Escamillo of Robert Massard sounds authentic too, if not so characterful as someone like Jose Van Dam. Andrea Guiot’s Micaela I like a lot. She does not display the creamy beauty of a Te Kanawa or a Sutherland, but she is much more convincing than them at playing the plucky, no-nonsense village girl. We must not think of Micaela as a wilting violet; she is actually quite a strong character. Not only is she able to hold her own with the soldiers in the first act, she has the strength to confront Carmen and the gypsies in the third act. Her voice is firm, clear and very French. She sounds just right to me.

Gedda of course had already recorded the role under Beecham with De Los Angeles. He does not have the heroic sound of a Domingo, a Vickers or a Corelli but, as always he sounds totally at home in French opera. In any case, is a big heroic voice what is required? Don Jose is basically a nice young man, somewhat repressed, who gets caught up with the wrong woman. A young man, who, once his passions are aroused, does not know how to control them. Gedda is superb at charting Jose’s gradual disintegration. He sings a beautifully judged Flower Song, with a lovely piano top Bb, is gently caring in his duet with Micaela, and suitably shamed when he meets her again. In the last act he is a man at the end of his tether, dangerous because he has nothing left to lose. As a performance I think it has been seriously underestimated. I find him entirely convincing, much more so than, say, Corelli, with his execrable French, in Karajan’s first recording of the opera.

And so we come to Callas. Many of the objections when the set first came out were not so much about her singing as about her characterisation, one critic opining that she was closer to Merimee than Meilhac and Halevy. But that’s an objection that makes no sense at all. Meilhac and Halevy may have watered down Carmen’s indiscretions with other men while still with Jose, but they still make it clear she is a free spirit, not to be tied down. In the 1960s, women were still fighting for equality (they still are). Much of the debate about the contraceptive pill in the 1960s centred around the fact that it would encourage promiscuity. People, especially men, were not comfortable with the idea of a sexually promiscuous woman, so Carmen’s character was often played down. The De Los Angeles recording with Beecham had been highly praised, but, love De Los Angeles though I do, can anyone really imagine her Carmen pulling a knife on a fellow worker in a cat fight? She is altogether to ladylike to even think of such a thing. But Callas is exactly what she is described in the text, dangereuse et belle, in Micaela’s words. This is a true free spirit. As she tells Jose in the last act, Libre elle est nee et libre elle moura! When she admits to her friends Je suis amoureuse, Callas gives the line an ironic twist, even more so on the following amoureuse a perdre l’esprit. We know absolutely, as her friends do, that this is the whim of the moment; the mood of the day, and that there will be others. Earlier her seduction of Jose is brilliantly charted too. Ou me conduirez-vous? she asks Jose, as he is about to take her to prison, and the little girl lost tone she uses is just what’s needed to draw him in. Later on when Jose comes to the inn and they end up arguing, some have found her rage too over the top, but there is justification for this too. When Jose tells her he has to go back to the barracks, that could be the moment she realises that maybe she is not in love with this milksop after all. Have a row, send him packing. That’s the best way to get rid of him. Only things don’t quite work out that way; her cry of Au diable le jaloux! is quite matter of fact. Finally she realises she is saddled with him, but is quite pragmatic. In fact, now that I think of it, the whole plot only works if you accept that Carmen was never in love with Jose in the first place; that he was first a challenge, then a convenience. Escamillo is much more up her street (for a while anyway); when he comes looking for her and Micaela comes looking for Jose, this is just the way out she is looking for. Unfortunately, Jose turns out to be even more unhinged than she had imagined, but defiant to the last, she refuses to give in to him, and staring death in the face, asserts her freedom from all men. No doubt this is what commentators found so disturbing. Some no doubt still do. It doesn’t make for comfortable listening.

Apart from a few squally top notes in the ensembles (which she didn’t need to sing anyway), her voice was absolutely right for the role at this stage in her career and the performance is full of miraculous detail. I notice something different in it each time I hear it.

When it was reissued, Richard Osborne in Gramophone wrote, “Her Carmen is one of those rare experiences, like Piaf singing La vie en rose, or Dietrich in The Blue Angel, which is inimitable, unforgettable, and on no account to be missed.”

I couldn’t have put it better myself.