This is an expanded version of something I wrote a few years ago.

Back in 2011, John Steane, an expert on voices and an eminent critic, died at the age of 83. He had his favourites of course (who doesn’t?), but I learned a lot from JBS over the years, and I do miss his wonderfully constructive musical criticism. When he was still active at Gramophone Magazine, the editor asked him to write an article detailing the twelve singers who had changed his life, the one injunction being that one of them should still be active as a singer. For someone who knew his writing, his choices didn’t come as much of a surprise. I recently re-read this article and it got me to thinking of who mine would be. I’ve stuck to just ten, but these are all singers, who have said something personal to me, the voices that have spoken to me down the years, from when I first started to enjoy opera and lieder as an impressionable teenager, up until now.

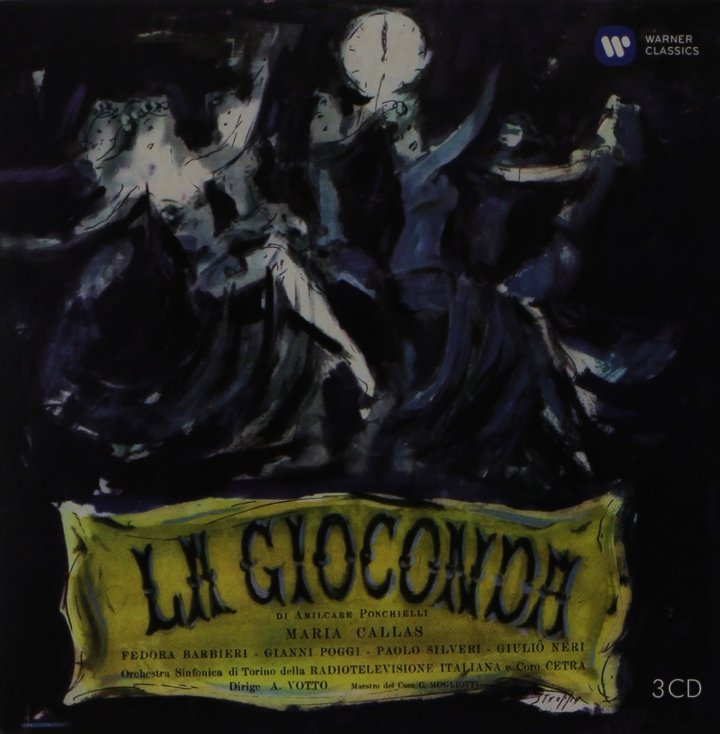

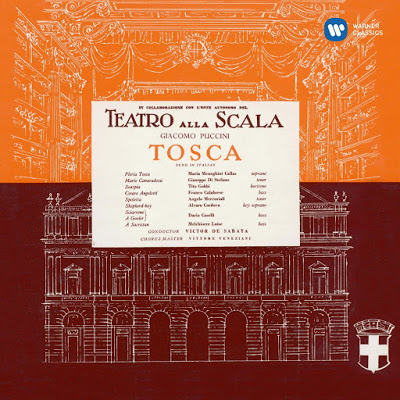

Anyone who knows me won’t be in the least surprised by my first choice. I first heard the voice of Maria Callas on an LP reissue of her first recordings, originally issued on 78s. The Mad Scene from Bellini’s I Puritani was coupled with the Liebestod (in Italian) from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and excerpts from her early Cetra recordings of La Traviata and La Gioconda. This was a voice like none I’d ever heard. It was a large voice, with dazzling flexibility, a rarity in itself, but what struck me most was the way that voice penetrated your very soul. It was a voice bursting with emotion. I may not have appreciated then her amazing musicality, but I certainly recognised the work of a genius. Callas made you feel that the music sprang from her throat newly minted, that she meant every word, every note. More than that, it was the way the voice could change from the sweet innocent Elvra to the womanly Isolde, from the passion of the courtesan Violetta, to the almost primeval sounds of her Gioconda. It hardly seems believable now, given that Callas’s recordings have formed the backbone of EMI’s (now Warner’s) Italian opera catalogue for years, but most of them were unavailable at the time. I slowly built up my collection by scouring second hand shops and pouncing on any imported issues that made their way into specialist record shops. As I slowly built up my collection, it was Callas who introduced me to the world of Italian opera. Nowadays I can be aware of some of the vocal failings, especially in the later recordings, but nobody has ever come within a mile of her fantastic musicality, and up until at least the mid 1950s, the voice was an amazingly responsive instrument. For evidence of her musical skills, no better example could exist than her Leonora in Il Trovatore, full of aristocratic phrasing and almost Mozartian delicacy. Though a little strained by some of the high lying passages on the Karajan recording of 1956, she still phrases like a master violinist, her sense of line and rubato unparalleled, the trills and cadenzas beautifully bound into the musical fabric of the whole.

She was also an amazing vocal actor, and though she has a voice that is instantly recognisable, she continually changes the weight of that voice to suit the character she is portraying. The woman who sings Lady Macbeth and Medea with such demonic force is hardly recognisable from the one who sings such a virginal and innocent Gilda, and though she may use the same lightness of touch for Amina in La Sonnambula as she does for, say, Rosina in Il Barbiere di Siviglia, they are still two completely different voice characters, and she can make us see that happiness is quite a different thing for Amina from what it is for Rosina.

Callas is still my touchstone for all the roles she sang (I can almost hear her in my mind’s ear in some of the ones she didn’t), and, though I recognise that some have made prettier sounds, there will always be a moment, maybe a single word, where Callas’s unique colouration will suddenly do something to nail the character as no other singer does. I regret that Walter Legge, excellent producer though he was, did not have the foresight to record her in much of the repertoire for which she was famous, and though I treasure all her studio recordings, it is a great pity that she didn’t get to record some of her greatest stage creations, like Lady Macbeth, Anna Bolena, Armida, Imogene in Il Pirata, and perhaps even Alceste and Ifigenia. Legge wouldn’t even touch Medea and Callas only got to record the opera by exercising a get out in her contract with EMI, though EMI did eventually release the recording, which had been made for Ricordi. I might also regret that Legge was so chary of stereo and that Callas was not accorded the kind of good stereo sound Tebaldi was accorded in her early 1950s recordings.

There is no doubt that Callas’s glamour and tempestuous personal life has done much to maintain her popularity, but she has been dead for 40 years now, the dust has settled, and it is surely her musical gifts for which she should be remembered; for Callas was not only a great singer, she was also one of the greatest musicians of the twentieth century. The great conductor Victor De Sabata once said to Walter Legge, her recording producer, “If the public could understand, as we do, how deeply and utterly musical Callas is, they would be stunned.” I have known her recordings now for the best part of fifty years and I continue to be newly stunned each time I listen.

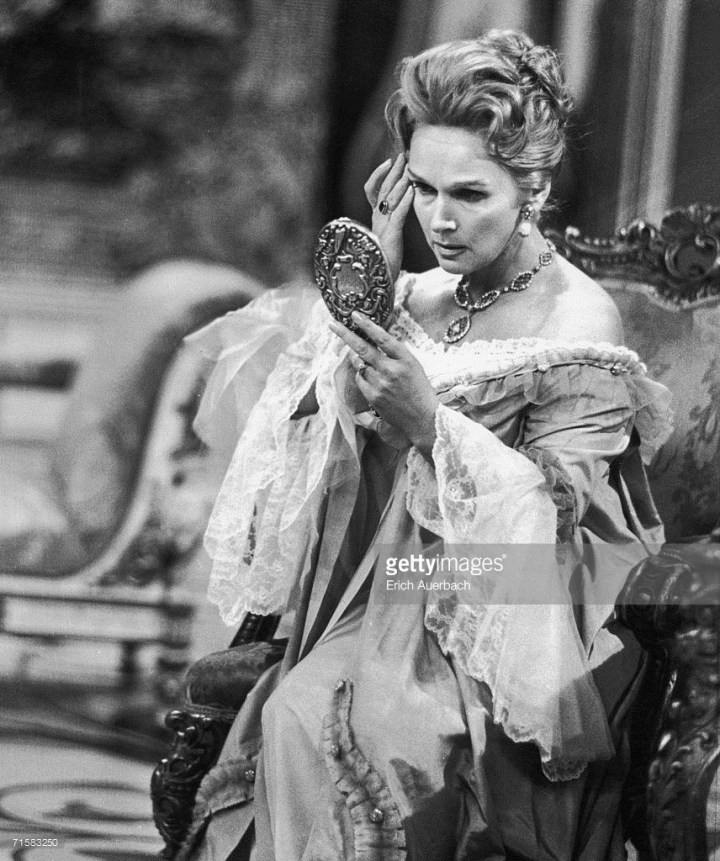

My next choice might seem a little more surprising, a singer as far away from Callas as it would seem possible to be, though I often think of them as flip sides of the same coin. Elisabeth Schwarzkopf is the singer who introduced me to Mozart, Richard Strauss and lieder. Her recordings of the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier, and of the Vier letzte Lieder were my first exposure to these works, and have remained in my collection ever since. Hers was a voice shot through with laughter, and she also made many great recordings of lighter works. Her album of Operetta Arias can lighten the spirits like no other. She and Callas admired each other enormously (their repertoires were very different of course), and though they only made one recording together (Puccini’s Turandot), they met often, as Schwarzkopf was the wife of Callas’s record producer, Walter Legge, on one occasion Schwarzkopf giving Callas an impromptu singing lesson in the middle of the restaurant at Biffi Scala. Schwarzkopf was a good person to ask. She rarely put a foot wrong, and it is this attention to detail, that some find gets in the way of the music. There can be a lack of spontaneity, it is true, and, where Callas is able to conceal the huge amount of work that goes into each of her musical recreations, Schwarzkopf can occasionally be accused of artifice. Her Liu in the above mentioned Turandot may not sound for one moment like a slave girl, but I love her singing of the role, so beautiful and so richly nuanced.

Still, when it comes to opera, I treasure her most in Mozart (an incomparable Donna Elvira, Countess and Fiordiligi) and Strauss (an unbeatable Marschallin and Countess Madeleine) and (in recital) in Agathe’s arias from Weber’s Der Freischütz, though I also prize her delightfully high spirited Alice in Karajan’s recording of Verdi’s Falstaff. In Lieder some find her singing too detailed, and she is often accused of being mannered. Well, I’d aver that all great singers have their mannerisms. It’s one of the things that makes them instantly recognisable, and I prefer to think of them as idiosyncrasies. Warner recently reissued all her EMI recital records in their original programmes, and though it means each disc is rather short for CD, it shows the care that would go into creating these recitals, the same care that would go into her programming of material for her recital programmes. Each of them makes eminently satisfying listening.

I remember many years ago attending one of Schwarzkopf’s Master Classes at the Wigmore Hall with my singing teacher, the late Ian Adam, who adored her incidentally. She was a very hard task master, rarely letting a student sing more than a few bars before stopping them, and watching the classes was a peculiarly frustrating experience. It must have been even more so for the students. But that was the way she studied and rehearsed herself. She was actually severely self critical, as is shown in the book Elisabeth Schwarzkopf: A Career on Record, in which she listens to some of her recorded performances with John Steane. On many occasions she dismisses performances of her own that Steane admires, pointing out faults that none of us can hear. Though Schwarzkopf herself had refrained from singing at the classes, at one point she did sing out for just a few bars, in an attempt to show the student how to bring moonlight into the sound of their voice. Well, as Ian said, to me “You can’t teach that. Either you can do it, or you can’t.”

Unfortunately I never got to hear Callas or Schwarzkopf live, but I did hear Dame Janet Baker quite a few times, though only in concert, never on the operatic stage, where she was equally at home. The first time was in a performance of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde at the Royal Festival Hall, whilst I was at college, a performance that has remained in my memory ever since. In a very different repertoire, she had an almost Callas like intensity and an ability to sing pianissimi that somehow reached the furthest recesses of the hall. Dame Janet introduced me to the music of Monteverdi and Handel, Bach and of course Elgar’s Sea Pictures (memorably coupled to Jacqueline Du Pre’s seminal recording of the Cello Concerto). She was also a great Berlioz singer. I actually prefer her Barbirolli recording of Les Nuits d’Ete (and a live one under Giulini) to Crespin’s famous one, and I doubt her recording of the closing scenes of Les Troyens has ever been bettered.

She recorded extensively for EMI, then Philips and, towards the end of her career, for such independents as Hyperion, Collins Classics and Virgin Classics, singing a vast range of repertoire that took her from the music of Monteverdi and Cavalli to Respighi, Britten and even Schoenberg, taking in Donizetti, Verdi, Schubert, Schumann, Liszt, Wagner and Mahler along the way. Some of her greatest recordings are those she made with Sir John Barbirolli, with whom she had a great rapport, The Dream of Gerontius, Sea Pictures, Les Nuits d’Eté, Shéhérazade and, maybe the greatest of them all, the orchestral Lieder of Mahler, particularly her wonderfully sensitive and inward performance of Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen. She was also world renowned for her singing of the lower part in Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, which I twice heard her sing live. She recorded it in the studio with Haitink, and there are at least three live recordings knocking around. Best of all of these is a Bavarian Radio broadcast under Rafael Kubelik, in which her singing of the final song, has a quiet intensity , which is almost too much to bear. So palpable is her emotional commitment to the music that I save this performance for rare occasions. Like Callas’s shattering performance of Violetta at Covent Garden in 1958, it reduces me to a quivering wreck.

Placido Domingo’s was a voice I first heard on record in an early recital of arias, but I will never forget the thrill of first hearing him live at the Royal Opera House, in La Fanciulla del West, if memory serves me rightly. Domingo certainly had presence and a glamorous voice to go with it. A real singing actor, he seemed to improve as a performer every time I saw him. Incredibly, he is still singing today, though he has moved over to the baritone repertoire recently, taking on such roles as Simon Boccanegra and Rigoletto. True, it is remarkable that a singer, and a tenor at that, can continue to sing into his seventies, but, great stage performer though he is, I am not sure that his excursions into the baritone repertoire have been entirely successful, and I prefer to remember him in the great days of his tenor glory.

In his early days, beautiful though his singing was, he could be accused of a somewhat generalised attitude to characterisation, but, over the years, he became more and more of a committed performer. Some of his roles he recorded several times, and one can hear how he progressed. The voice always had a dark, burnished quality, and the very top of the voice was never as easy as some, but, paradoxically, it sounds freer to me in his middle period than when he was young. Still, he wasn’t ashamed to admit that his top Cs were hard won, and I actually applauded his decision to omit the unwritten ones, in Il Trovatore at Covent Garden, rather than doing what so many do and attempting to trick the audience by transposing Di quella pira down. His Otello is a towering achievement, and, for many years, there was no one around who could challenge his hegemony in the role. He made three recordings of the role at different stages of his career, and there are quite a lot of visual documents of his portrayal, including the controversial Zeffirelli film.

Free, ringing top Cs were never a problem for Fritz Wunderlich, who had a voice of overwhelming heady beauty. He died just before his 36th birthday, at a time when his interpretative artistry would have been reaching its maturity, his final concert in Edinburgh being testament to that. However if you ever want to hear someone just revelling in the sheer joy of singing, then listen to his DG performance of Lara’s Granada. Admittedly it is in German and the splashy arrangement is pretty vulgar, but he sings with a freedom and passion that would be the envy of any Latin tenor. For me, Wunderlich’s singing always conveys a sheer joy in the act of singing itself. Though he died young, he made many recordings, and it is this sense of joy that I most prize.

Interpretively, his recordings of Lieder don’t probe as deeply as some no doubt, but he was still young when he made them and unfortunately hadn’t reached his interpretive maturity before he died. For instance, the Dichteriebe he sings at his final concert in Edinburgh is a great deal more interesting than the recording he made for DG a year or so earlier. He did leave us arguably the greatest Tamino on disc, on Böhm’s Die Zauberflöte, which for once has a truly heroic dimension, a superb rendition of the tenor songs in Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde (both in the studio under Klemperer and live under Krips), and of the tenor arias in Karajan’s recording of Die Schöpfung. Most of his Italian and French repertoire was sung in German, but still has a golden, Italianate warmth, and we do have at least one recording of him singing Verdi in Italian, a live performance of La Traviata from Munich with the young Teresa Stratas as Violetta. His early death was a tragedy beyond reckoning, as one wonders what he might have gone on to achieve. His Steersman on the Konwitschny recording of Der fliegende Holländer gives notice that he could have gone on to sing Lohengrin at least, and, in Verdi, what a wonderful Duke, Don Carlo or Riccardo he would have made.

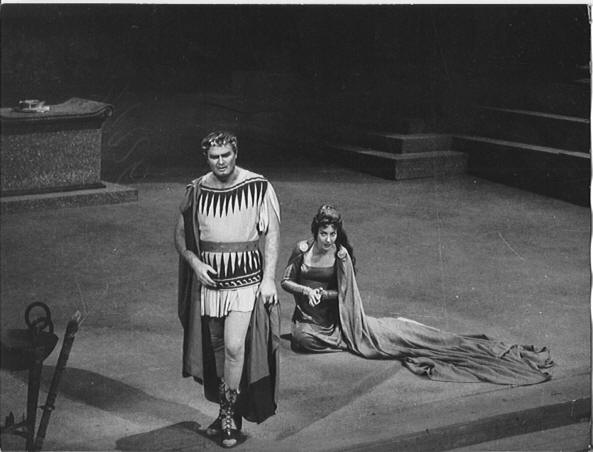

Staying with tenors for the moment, I turn to Jon Vickers, who had a voice and manner of startling individuality, and an intensity of performance that could almost be too painful to listen to. Though well known for his Tristan, his Siegmund, his Florestan and his Grimes, he first came to prominence singing in Italian opera. In 1958 he sang Giasone to Callas’s Medea in Dallas, and then also in London, at La Scala and at the ancient Greek theatre at Epidaurus. He had enormous respect for Callas and named her as one of the two people to have the most profound effect on opera in the post World War II period (the other being Wieland Wagner). He was also Don Carlo in Covent Garden’s legendary Visconti production of Don Carlo, conducted by Giulini, which also had Gobbi and Christoff in the cast. With a voice of such power and penetration he naturally progressed to Wagner, singing towering performances of Tristan and Siegmund. His Otello suffered like no other and his Peter Grimes, mercifully preserved on film, is one of the greatest creations of all time. Like all the singers in this survey, his voice is instantly recognisable, his style somewhat idiosyncratic, but intensely musical. There is always something monumental about a Vickers performance. On disc, I find his Aeneas (in Berlioz’s Les Troyens), his Florestan, his Tristan and his Otello unequalled by any who have followed, and his Grimes, so totally different from Pears, utterly convincing.

Next on my list are two more sopranos, one from well before my time and one who died only recently. I first heard the voice of Maggie Teyte in a performance of Duparc’s Chanson Triste and was totally captivated. Her performance of the song remains my yardstick to this day. Born in 1888, she was cast in the role of Mélisande by Debussy himself, replacing the creator of the role, Mary Garden. She prepared the role by studying with Debussy, and is the only singer ever to be accompanied in public by the composer (in a performance of his song Beau soir). She married twice and went into semi-retirement after her second marriage in 1921. Like her first marriage, this ended in divorce and Teyte had some difficulty reviving her career afterwards. For some time she appeared in music hall and variety, which explains much of the lighter repertoire she sang and recorded. However the recordings of Debussy songs she made with Alfred Cortot in 1936 attracted a lot of attention, helping her to gain a reputation as one of the leading interpreters of French song, The voice remained pure, without a hint of excessive vibrato even into her sixties, and she made her final concert appearance at the Royal Festival Hall at the age of 68.

I would recommend any and all of her recordings of French song, as well as her wondrous rendering of ‘Tu n’es pas beau’ from La Périchole, which shows off to advantage her gloriously individual chest tones, and a twinkle in the eye. A private recording of her singing bits of Salome (to a piano accompaniment) show that she might even have been an ideal Salome, the silvery purity of the voice being close to Strauss’s ideal, and it is a great pity that plans for her to sing the role at Covent Garden never came to fruition.

Truth to tell, I hadn’t much liked Victoria De Los Angeles when I first heard her (as a rather insecure and out of sorts Hoffmann Antonia) and I think it was probably her record of the Canteloube Chants d’Auvergne that first led me to investigate further. She had a particularly wide song repertoire, which took in early and late Spanish composers, as well as Lieder by Schubert, Schumann and Brahms and French song. One of her greatest quality was her charm and that quality the Italians refer to as morbidezza, meaning that, on the operatic stage, she was most at home playing gentler heroines. That Antonia was misleading and later I discovered she could be the perfect Marguerite (Faust), Butterfly, Rosina and Mimi displaying a golden voice allied to a winning personality. Best of all perhaps is her Manon in Massenet’s opera. Where some make the character too knowing, De Los Angeles emphasises the childlike innocence and delight in pleasure that is at the heart of Manon’s downfall. She was also a superb Desdemona (in a live broadcast from the Met) and it’s a great pity she never got to record the role commercially.

Her Carmen on the Beecham recording has been much praised, but here I find her less convincing, though, as usual, her singing is unfailingly musical. I just can’t imagine De Los Angeles’s Carmen pulling a knife on a fellow worker. She is altogether far too ladylike. She is on record as saying that she based her Carmen on the Andalusian gypsies, who were known for their charm, a quality De Los Angeles had in abundance, but my Carmen is dangereuse est belle (Micaela’s description) and De Los Angeles, charming and adorable as she was, never sounds dangerous to me.

So far the list is rather top heavy with high voices, so I am happy to include as my next choice a baritone, colleague of Callas’s and one who encompassed many of her qualities. Like Callas, Tito Gobbi had an immediately recognisable voice and always sang with a wealth of colour and understanding. I can still remember the shattering effect of my first listen through Rigoletto, actually the first ever time I’d heard the opera. His cries of “Gilda” at the end of Act 2 after she has been abducted went straight to the heart. He may not have had the most beautiful baritone voice in the world, but, like Callas’s, it had a myriad of different colours. And like her, though always recognizably himself, he was always able to change his timbre to suit the role he was playing.

We are fortunate indeed that, though they sang rarely on stage together (most famously in Zeffirelli’s renowned Covent Garden production of Tosca), they made many recordings together; two recordings of Tosca, Lucia di Lammermoor, Aida, Un Ballo in Maschera and Il Barbiere di Siviglia, their collaboration possibly reaching its apogee in Rigoletto, with its long series of duets for father and daughter. Again, like Callas, he could put more meaning into a line of recitative, even into a word, than bars of singing by less dramatically attuned singers. The way he utters the single word Amelia in Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera, when he discovers the identity of Riccardo’s midnight tryst, resonates in my mind’s ear even now. Some would aver that he didn’t have a true Verdi baritone voice, but, as I think now of the parade of Verdi roles he sang – Rigoletto, Amonasro, Posa, Simon Boccanegra, Renato, Iago, Germont, Falstaff, Nabucco – they all emerge as distinct and different characters. Of how many other singers can you say that? Scarpia in Puccini’s Tosca might be his most famous creation (a repulsively reptilian character, who is both a gentleman and a thug) but it is in Verdi that his musical skill is most evident. What a tragedy that Walter Legge never had the foresight to record Macbeth with him and Callas as the murderous couple.

Looking back at this list of singers, I realise that they all have certain things in common; the individuality of their voices (you only have to hear a few notes to know who it is) and their ability to make the listener see as well as hear. This is no less true of countertenor, David Daniels, a singer still very much before the public today. Some years ago, I was more or less dragged to a concert of Vivaldi sung by Daniels and accompanied by Europa Galante conducted by Fabio Biondi. Till then, apart from the Four Seasons and the Gloria, I had had little enthusiasm for Vivaldi’s music and had a total antipathy for countertenors in general. Daniels changed all that. Here was a voice of surpassing beauty, coupled to a marvellously natural personality. It was a total conversion and Daniels has now opened the door on a whole world of music I had previously ignored, which shows it is never too late to expand one’s horizons. I have hardly missed any of his appearances in this country, and, like all the singers on this list, he has a gift for communication vouchsafed to just a few.

He has also expanded the repertoire for countertenors, embracing American song, Lieder, French song and even Broadway. Sometimes the experiments don’t quite work. For instance, though his singing is, as ever, unfailingly musical and filled with meaning, the countertenor voice, even one as mellifluous and beautiful as his, just doesn’t have the range of colour required for a piece like Les Nuits d’Eté, and though I appreciate and enjoy his excursions into nineteenth century and modern repertoire, it is for the music of the baroque, and especially Handel, that I turn to him. In his early days his coloratura singing was sensational, but I treasure most his deeply felt singing of some of Handel’s slower arias. In an aria like Scherza infida he holds the line beautifully and firmly, but evinces a pain that is almost palpable. No other singer I have come across quite makes the same effect in this music. I am guessing that he will be coming towards the end of his career now, and I count myself fortunate indeed to have been able to experience his singing live whilst he was in his prime. I saw him so many times, that I swear he actually spotted me in the audience on several occasions, and acknowledged my applause with a nod in my direction.

Of course, apart from these singers, there have been many memorable performances. I recall the excitement of the first time I heard a really world class singer, Helga Dernesch in Fidelio and as the Marschallin (still the best I’ve seen live on stage); Agnes Baltsa’s Carmen with the no less memorable Don Jose of Jose Carreras; ditto Baltsa’s thrilling Eboli; the superb Dejanira of Joyce Di Donato; Angela Gheorgiu’s first Violetta, and Ileana Cotrubas‘s Violetta too; Roberto Alagna’s first Romeo (in the Gounod opera); Kiri Te Kanawa’s exquisitely, if placidly, sung Fiordiligi (with Baltsa again, as an adorably funny Dorabella); Renee Fleming in Previn’s A Streetcar Named Desire; Margaret Price and Lucia Popp in concert. I also regret never seeing live the wonderful Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, who was taken from us far too early and at the height of her artistic maturity, and whom I first remember in a Proms concert on TV, at which she was the radiant soloist in a performance of Elgar’s The Music Makers. These too will always stay in the memory, but I send my gratitude to the ten on my original list, for through them I have discovered a whole world of great music. They may not necessarily be the ten greatest singers of all time but they have enriched and enlightened and can truly be called singers who have changed my life.