Don Carlo, or more properly Don Carlos, to use its French title, that great, sprawling, flawed masterpiece, is one of my favourite Verdi operas, maybe even my favourite. Admittedly it doesn’t have the coherence of Aida or Otello, or even Rigoletto, but enshrined in it is some of Verdi’s greatest music, and I believe that Act IV, Scene i is one of the greatest scenes in all Verdi. Starting with that mournful cello introduction to Philip’s despairing Elle ne m’aime pas, through the magnificent duet (more a duel )between the two bass voices of Philip and the Grand Inquisitor, on to the superb quartet for Philip, Rodrigue, Elisabeth and Eboli, to Eboli’s thrilling O don fatal, Verdi doesn’t put a foot wrong. As pure theatre and drama, it can hardly be bettered. It also enjoys some of the most complex characterisation in all Verdi. The tenor Carlos, is really an anti-hero, a rather pathetic character, desperate for the recognition of a cold, distant father, who wishes his son were more like his friend and confidant Rodrigue, the only really noble character in the opera. Philippe is also a weak character. He strives to be a strong leader, but mistakes intransigence for strength, and, ultimately, is putty in the hands of the church. He does not think for one moment about the effect of his decision to marry Elisabeth himself instead of Carlos, an act of pure selfishness. Elisabeth, disappointed in love, treated appallingly by Philippe, is both regal and compassionate, and Eboli is flighty, hot tempered, and ultimately remorseful.

Over the years I’ve seen the opera a few times and acquired three recordings, though what I actually have is recordings of three different operas. Giulini in 1971 goes for the five act version, in Italian translation, which restored the Fontainebleau Act, and puts Carlo’s Io la vidi back where it belongs in the Fontainebleau act; Karajan in 1979 chooses Verdi’s four Act version (also in Italian, in which Verdi deleted the whole of the first act, transferring Carlo’s Io la vidi to the Monastery Scene, which now becomes Act I, Scene i; Abbado in 1983 conducts the original five act version in French, and adds an appendix of music cut from the first performance, excised from the 1882-83 four act version, or recomposed in that revision. Yes, I know. Complicated, isn’t it?

Don Carlo(s) is a long opera, and I listened to my three recordings over a period of several days, starting with the Giulini, going on to Karajan and finishing with Abbado.

The Giulini has acquired something of a classic status, and though probably not quite on the level as the same conductor’s Don Giovanni, it does a great deal to justify its high regard. First of all, Giulini has just about the best cast that could have been assembled at the time. That said, Domingo is not yet the artist he was to become. His singing is never less than musical, and he sings with commitment, but there is something slightly generalised about his performance, with nothing much to distinguish Carlo from any other Verdi tenor hero. Milnes sings a noble, forthright Rodrigo, my favourite of the three on these recordings. Raimondi is a little light voiced as Fillipo, a role that really cries out for the dark, buttery tones of a Pinza or a Christoff, but he is suitably tortured and his voice contrasts well with the black voiced Inquisitor of Giovanni Foiani.

Caballé’s voice was at its most beautiful at this time, and, though she too can be a little generalised, she is never less than involved and involving. Her soft singing, as you might expect, is exquisite.

Verrett is, quite simply, magnificent, and without doubt one of the best Ebolis on disc. Recorded before she started moving up to the soprano repertoire, her voice is in thrillingly exciting shape.

Giulini had of course conducted the opera a few years previously at Covent Garden, in a production by Visconti which went a long way to restoring the opera to its rightful place in the Verdi canon, It starred Jon Vickers, Tito Gobbi, Boris Christoff, Gré Brouwenstijn and Fedora Barbieri, and it served Covent Garden very well over the years. I even saw Christoff myself in the opera in one of his last operatic appearances. Giulini’s credentials as a Verdian are never in doubt. His tempi can be on the spacious side, but he has a sure sense of the work’s structure. The 1971 analogue recording is wonderfully natural, the voices beautifully caught, and still sounds good on CD.

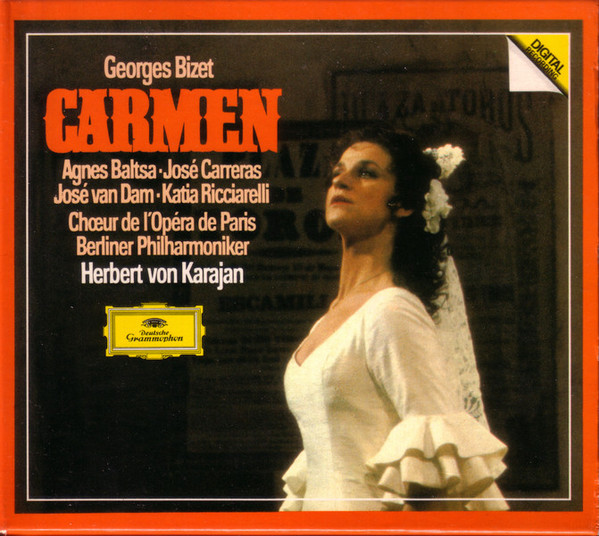

The first thing that strikes me, and annoys me, about the Karajan recording is the sound. In an acoustic that is impossibly wide ranging, the voices, lighter and more lyrical than was often the case, are so far recessed that it is often difficult to hear them. One of the worst instances of this is the beginning of the scene in the Queen’s Garden at night. With the sound turned up to a comfortable level for Karajan’s beautiful evocation of a heady summer night, Carreras is all but inaudible at his first entry. I turn up the sound in order to hear him better, only to be blasted out of my seat at the next orchestral tutti. This is but one example, but it happens all the time, and is, in my opinion, a serious blot on what is actually a rather good performance.

Karajan, who also had a great deal of experience in this opera, is also spacious, but the performance still bristles with drama. I just wish he didn’t constantly push the orchestra forward at the expense of the singers, who are often submerged in the orchestral textures.

I liked Carreras’s Carlo very much. His legato isn’t as good as Domingo’s, but he is better at suggesting the character’s unhinged nature. Cappuccilli is good, without being distinctive. He has a good legato, and superb breath control, but he is a little anonymous, and this performance is not generally at the same high standard of his Boccanegra and Macbeth for Abbado. Ghiaurov is Filippo, but his voice was already showing signs of wear by this time, and I find him less interesting than Raimondi in the same role, who is now the Inquisitor, and a mite too light of voice for that role.

This was Freni’s first excursion into heavier repertoire, and she makes a very appealing Elisabeth. As always her singing is unfailingly musical, but lacks the grandeur Caballé brings to Tu che le vanita. Baltsa is just as exciting as Verrett, her voice, at this time in her career, seamless from top to bottom. I saw her in the role at Covent Garden a few years after this recording was made and she brought the house down, generating the kind of excitement that is all too rare in the opera house today. I really couldn’t choose between her and Verrett. Both are fantastic.

And so on to Abbado, which I find operates on an altogether lower voltage.

Having taken the decision to perform the opera in French, it would seem somewhat perverse to use singers who have little or no (Domingo excepted) proficiency in the language, and it is Domingo who is the standout performance in this set. Paradoxically, ten years after making the Giulini recording, the top of his voice sounds much more free, and he is much more inside the character than he was before, a highly strung and nervous portrayal.

Nucci is a four-square, dry old stick of a Rodrigue. Raimondi is back to playing Philippe, but his voice has lost some of its bloom, and Ghiaurov is sounding increasingly grey voiced as the Inquisitor.

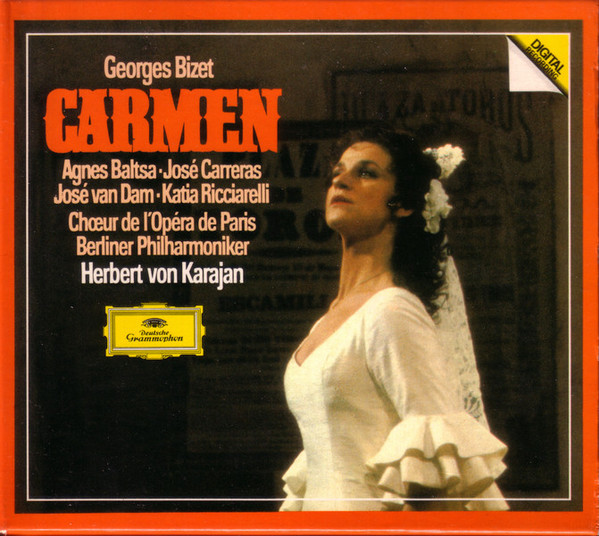

Ricciarelli I have equivocal feelings about. She is the definitely the most affecting of the three Elisabeths, but also the most fallible vocally. However it’s a performance I’ve come to admire more over the years. Valentini-Terrani is much too light voiced for Eboli, and O don fatal taxes her to, and beyond, her limits. She is definitely no match for either Verrett or Baltsa.

Though it is the newest, and digitally recorded, the sound is unaccountably murky, nowhere near as clear, or as natural, as the Giulini, and Abbado’s conducting lacks energy and authority. He doesn’t have the same structural control he evinces in his recordings of both Simon Boccanegra and Macbeth.

My conclusion is, then, that Giulini retains its place at the top of the field, though I will on occasion want to listen to Karajan and Abbado, for some of the individually excellent performances.

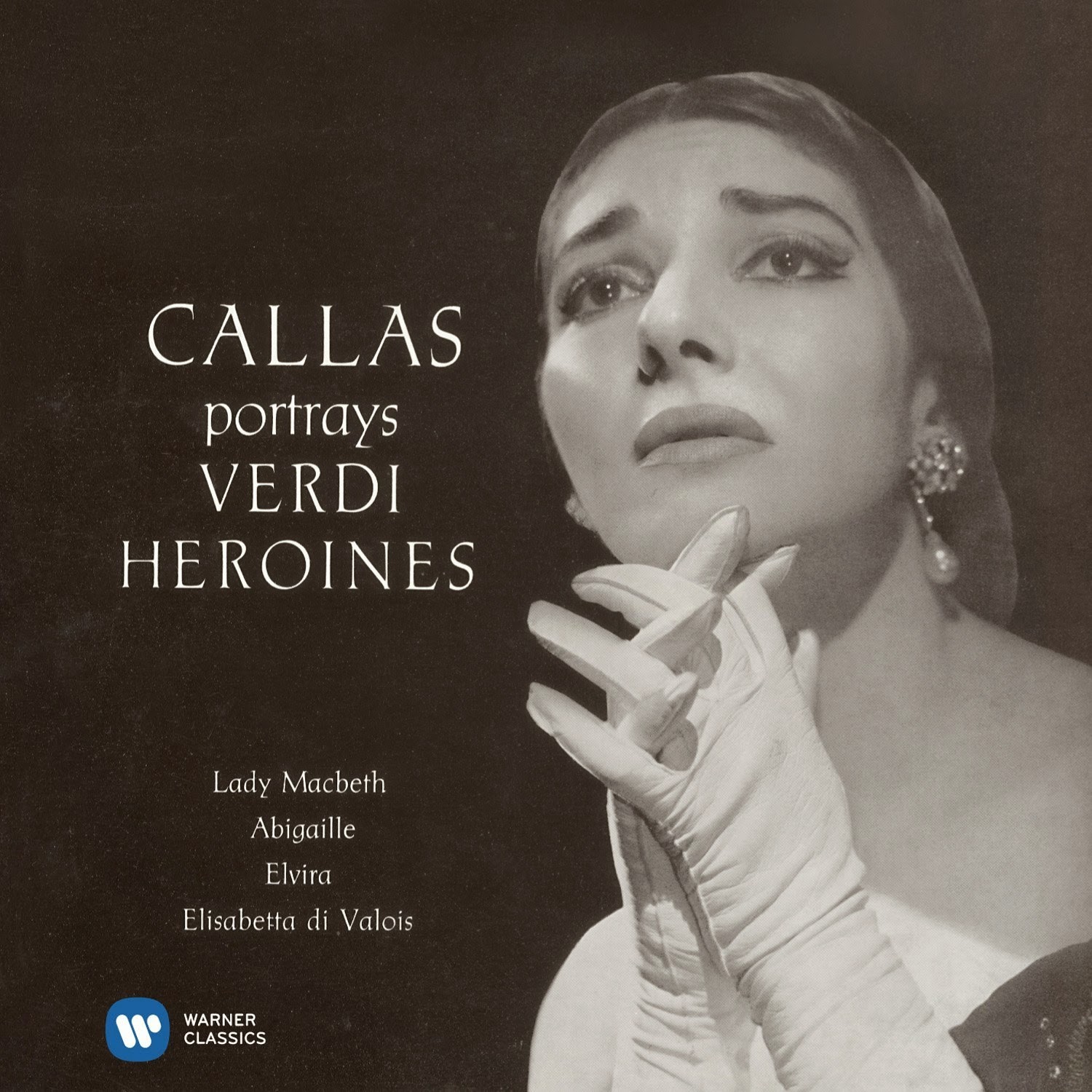

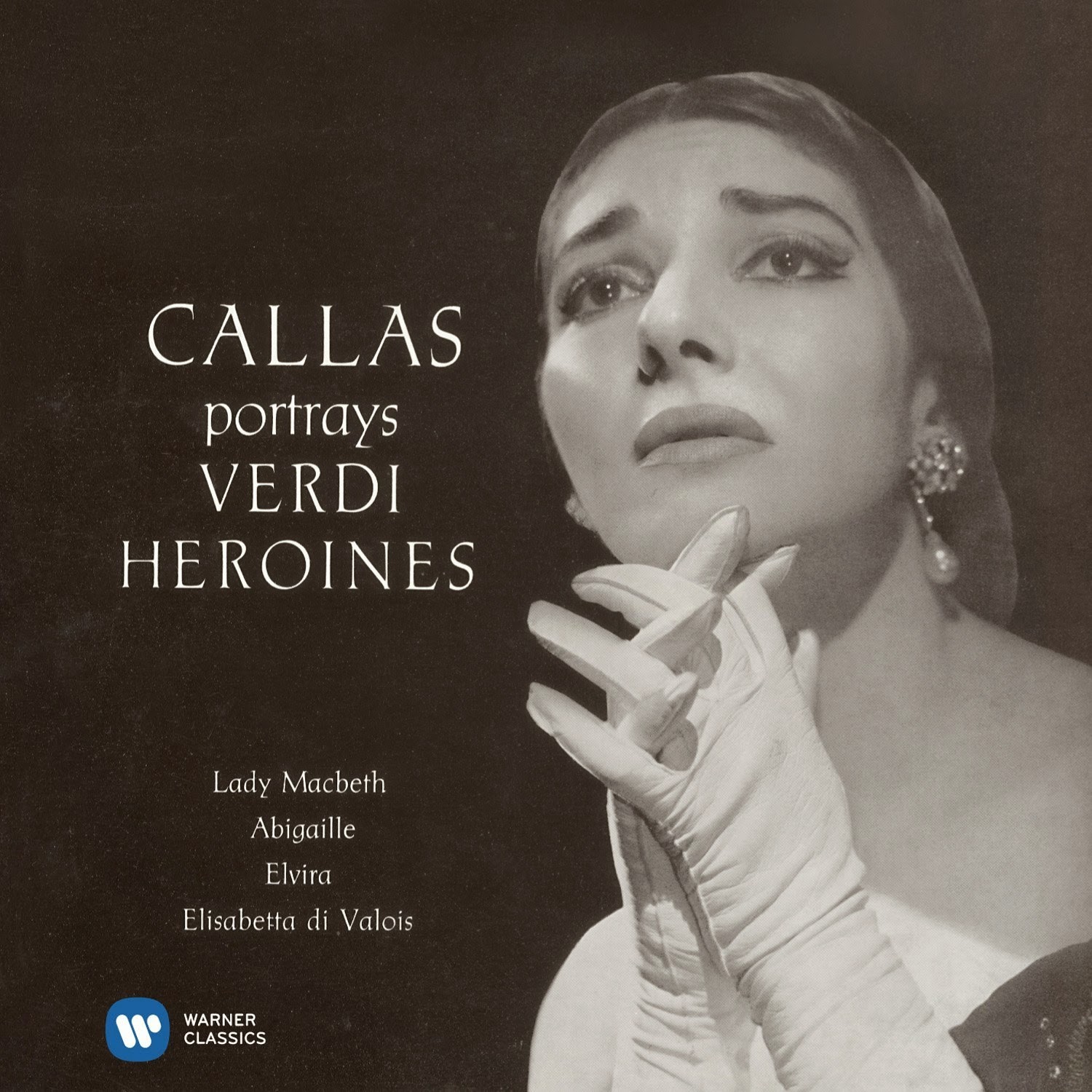

As a codicil to this, I would mention that my introduction to the opera was Callas’s magnificent recording of Tu che le vanita, an aria she obviously had a great deal of affection for, as she regularly programmed it into her concert repertoire. Callas only sang the role of Elisabeth once, at La Scala in 1954, and unfortunately none of the performances were recorded, but she makes more of the scene than anyone. It is grandly voiced, her breath control prodigious, but she effectively binds together its disparate elements. It is, in Lord Harewood’s words, a performance of utmost delicacy and beauty and I would recommend it to anyone who loves this opera.