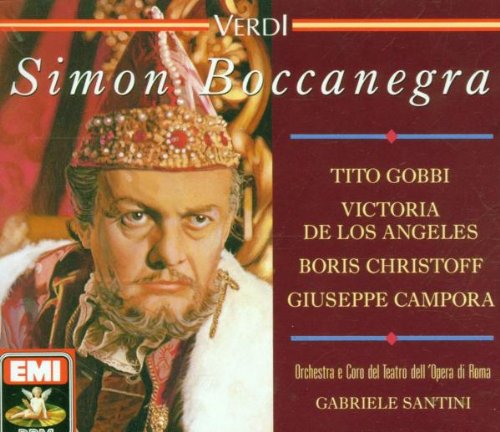

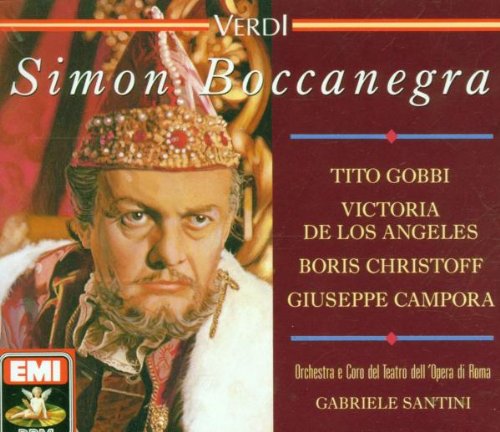

Abbado’s superb La Scala recording of Verdi’s great masterpiece pretty much sweeps aside all others, but this one, despite less than brilliant mono sound with an orchestra and chorus dimly recorded, despite Santini’s ploddingly prosaic conducting, demands to be heard, due to three distinguished, transforming performances.

Gobbi was in prime vocal form when the set was recorded, and though he does not quite have the vocal reserves of Cappuccilli, he creates the most rounded, most movingly tortured Doge you are ever likely to hear. Christoff, too, could hardly be bettered, brilliantly charting the change from implacable revenge to conciliation in the final scene with Gobbi’s Doge. To make our cup runneth over, we have De Los Angeles in one of her rare excursions into Verdi, singing with total communication, commitment and of course beauty of tone, particularly in the middle register, where most of the role lies. The downward runs in the final ensemble are absolutely exquisite. Campora may not be quite on their level (and Carreras on Abbado’s set is almost ideal) but he isn’t bad at all.

All three principals, I’d take (just) over their DG counterparts, but that recording benefits from Abbado’s superb pacing of the score, the wonderful playing of the La Scala orchestra, and warm, beautifully balanced stereo sound. So, for the opera itself, I’d take Abbado, one of the classic opera recordings, but for three superbly characterful performances, I choose Santini.