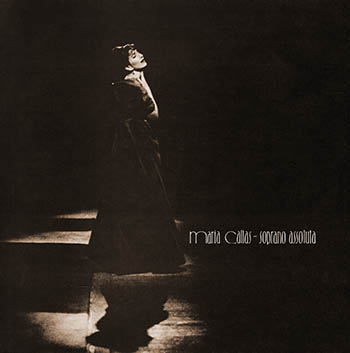

This is a superb compendium of recordings taken from live concerts given by Callas between 1949 and 1959. It is being offered as a FREE download (yes, you read that right, free) from Divina Records, so surely there can be no reason not to snap it up while you still can. The sound, while hardly state of the art, is not bad for the period, all of the performances having been taken from radio broadcasts. Taken from BJR LPs, transfers are up to Divina’s usual high standards and the download comes with an excellent pdf of the booklet which accompanied the original release.

The first track is actually her first 78 recording, made for Cetra in 1949, a beautiful performance of Casta diva and Ah bello a me ritorna, though without the opening and linking recitatives in which Callas always excelled. The aria is ideally floated, the scales and coloratura in the cabaletta stunning in their accuracy. We next turn to a radio concert recorded for Turin radio in 1952, with Oliviero de Fabritiis conducting. Callas was obviously out to demonstrate her versatility, and was also trying out for size a couple of roles she would sing later that year, Lady Macbeth and Lucia. To Lady Macbeth’s Letter Scene and the first part of Lucia’s Mad Scene, she adds Abigaille’s Ben io t’invenne from Nabucco and the Bell Song from Lakmé. She is in stupendous voice in all, the high E in the Bell Song ringing out here much more freely than it does in the 1954 recording. Not only is the singing technically stunning, but the contrasts she affords as she switches from the powerfully ambtious Lady Macbeth, to the sweet and maidenly Lucia, from the demonically triumphal Abigaille to the improvisatory story-telling of Lakmé are simply out of this world. You really don’t hear singing like this nowadays.

Next we move to a 1954 Milan concert, starting with her justly famous and technically brilliant recording of Constanze’s Martern aller Arten from Die Entführung aus dem Serail (sung here in Italian as Tutte le torture), her one Mozart stage role. Not only does she execute the difficulties with ease, she sounds properly defiant. It is a thrilling performance. Louise’s Depuis le jour (sung in French) suits her less well, and the performance is marred by occasional unsteadiness. Nonetheless it is hard to resist the quiet intensity of her intent. Armida’s D’amore al dolce impero from Rossini’s opera is, like the Mozart, stunningly accomplished, even if some of the more daring variations from the Florence complete performances have been trimmed down. The bravura of the singing is still unparalleled. The last item from this concert is Ombra leggiera from Meyerbeer’s Dinorah, a rather empty piece, which is hardy worth her trouble, though it improves on the studio recording with the addition of the opening recitative and the contribution of a chorus. Her singing is wonderfully accomplished, the echo effects brilliantly done, but it is not a piece I enjoy.

Another Milan concert, this time from 1956, brings us her best ever performance of Bel raggio lusinghier from Semiramide, though she adds little in the way of embellishment and the effect is less thrilling than her singing of the Armida aria. We get her first version of Ophélie’s Mad Scene from Hamlet (sung here in Italian rather than the original French of the studio recording), which is superb, it’s disparate elements brilliantly bound together. We also have a beautiful performance of Giulia’s Tu che invoco from La Vestale, which seques into a rousing performance of the cabaletta, and she revisits the role of Elvira in I Puritani with a lovely performance, with chorus and soloists, of Vieni al tempio.

From Athens in 1957, there is a dramatically exciting performance of Leonora’s Pace, Pace from La Forza del Destino, in which she manages the pitfalls of the piano top B on invan la pace better than you would expect for post diet Callas. Her performance of Isolde’s Liebestod (again in Italian) is very similar to the Cetra recording, warm and feminine, passionately yearning.

From the 1958 Paris Gala we have her minxish Una voce poco fa from Il Barbiere di Siviglia, with its explosive ma, as Rosina warns us she is not to be messed with. She sings in the mezzo key with added higher embellishments. This is followed by a couple of lesser known performances from a UK TV special, conducted by Sir Malcolm Sargent. Mimi’s Si mi chiamano Mimi is similar to the performance on the complete recording, charming and disarming, whilst Margarita’s L’altra notte from Mefistofele is a touch more vivid, a little less subtle than the studio recording.

Just one item from the 1957 rehearsal for the Dallas Opera inaugural concert, the Mad Scene from I Puritani. Though, by this time, Callas’s voice had been showing signs of deterioration, Bellini’s music still suits her admirably, and she sounds in easy, secure voice here up to a ringing top Eb at its close. The scale work is as supple as ever, and she executes its intricacies with ease even when singing at half voice.

To finish off we have the Mad Scene from the 1959 Carnegie Hall concert performance of Il Pirata. It had been a variable evening, with Callas’s colleagues hardly in her class, but here, left alone on the stage, Callas responds to the challenges of the final scene superbly, the cavatina, in which she spins out the cantilena to incredible lengths, becomes a moving lament to her son, and the dramatic cabaletta is then thrillingly flung out into the auditorium. The audience unsurprisingly go berserk.

How lucky we are to have these wonderful live performances preserved in sound, and how grateful we are to Divina Records for offering them to us free of charge. Nobody need hesitate.