In this article I propose to discuss in chronological order all the roles Callas sang on stage. Rather than going into too may details about the various recordings I have provided links to reviews elsewhere in my blog. These will all open in a separate tab.

Most of you will know by now that this year is the 100th anniversary of the birth of Maria Kalegeropoulou, known to the world as Maria Callas. Born to Greek immigrant parents in New York in 1923, her mother took her back to Greece in 1937, where she studied with the coloratura soprano Elvira de Hidalgo before joining the Greek National Opera in 1941. After the war she returned to America in 1945 to be with her father in the hope of kick starting an international career in the States, but she had little success and in 1947, after auditioning for the veteran tenor, Giovanni Zenatello, who had been assigned the task of finding singers for a production of Ponchielli’s La Gioconda in Verona, she sailed to Italy where she lived for the rest of her active career. De Hidalgo had told her that her future lay in Italy, not America, and her words turned prophetic. In Verona she worked with the famous conductor Tullio Serafin, who would become her mentor and the major influence on her career and also met her future husband, Giovanni Baptista Meneghini. Her stage career was not long, spanning 26 years if we count her first student performance in 1939.

Her repertoire in Greece makes for very interesting reading, embracing both opera and song, but only one of the roles she sang there (Tosca) remained in her active repertoire after her arrival in Italy in 1947. The first complete opera she ever sang was Cavalleria Rusticana at the age of 15, whilst still a student. She sang it once again with the Greek National Opera in 1944 and then never again, except for the 1953 studio recording which we are fortunate to have as Callas wasn’t originally scheduled to sing it. Reportedly the mezzo who was engaged for the recording was having trouble with her top notes and Callas stepped into the breach last minute. It has remained a top recommendation for the opera ever since, and is the first of my essential Callas recordings for all that it played such a small part in her career. Callas’s next student role was Suor Angelica, a role she never sang again, though she did record the aria Senza mamma for her Puccini recital of 1954.

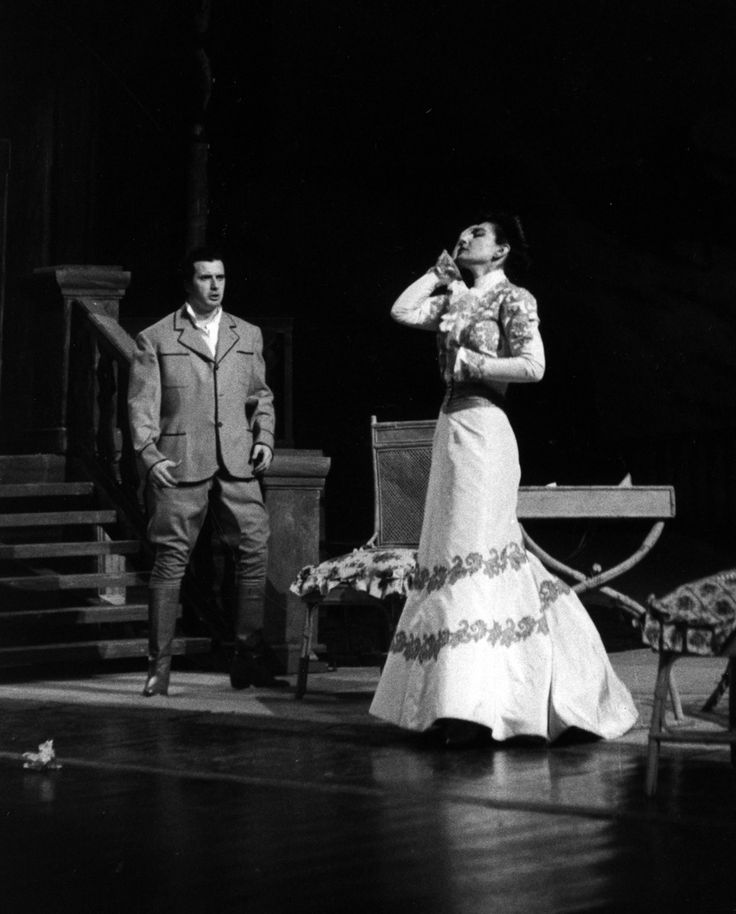

In 1941 she joined the Greek National Opera, her first role there being Beatrice in Suppé’s Boccacio, but it was her next role that was to have much more signifcance for her. She first sang Tosca in 1942, a role with which she is now particularly associated no doubt because of the famous De Sabata recording of 1953 (absolutely essential and one of the undisputed classics of the gramophone) and the famous Zeffirelli production of 1964, which was seen both at Covent Garden and in Paris. Callas herself expressed a certain amount of antipathy for both the role and the opera, and, though she sang it quite a bit in her early career, she hardly sang it at all after making the 1953 recording (and never at La Scala) until the flurry of performances in London, Paris and New York in 1964 and 1965. Indeed, after a couple of performances in Genoa in 1954, she only sang it at her two seasons at the Met. The second 1964 recording of the opera has its attractions too, but if I were to supplement the De Sabata recording, I would go for the live one of the opera at Covent Garden in 1964 under Cillario, again with Gobbi as Scarpia, which has been released by Warner in excellent sound. Also essential would be the video of Act II of the opera, filmed on stage at Covent Garden in 1964, a superb memento of two towering figures of the operatic stage. If anyone doubts the validity of opera as drama, then they should definitely watch this.

However, though the opera was certainly significant in her career, I do not think of it as one of the four cornerstones on which she forged it. Those would be Norma, Violetta, Lucia and Medea, all roles that were more suited to her rarified gifts and the ones she sang most often during the years of her greatest fame.

Her other roles at the Greek National Opera were Maria in d’Albert’s Tiefland, Smaragda in O Protomastoras by the Greek composer, Manolis Kalomiris and Leonore in Fidelio, which she sang in Greek. Of these, I always think it a shame that she never sang Leonore again.

After returning to New York, being rejected by the Met and after the collapse of a new opera company in Chicago which she was to have spearheaded in the role of Turandot, she set sail for Italy on 17 June 1947, arriving in Naples 12 days later. She went straight to Verona where she immediately started rehearsals for La Gioconda, making her international debut on August 2nd.

No doubt due to her two recordings of the opera, Gioconda is undoubtedly considered a Callas role, but in fact she didn’t sing it that often. She sang it again in Verona in 1952, then in the1952/1953 season at La Scala, which was preceded by her first recording of the opera for Cetra. After the La Scala performances she never sang the role again until the EMI stereo recording of 1959. I’ve always found it difficult to choose between these two recordings and really wouldn’t want to be without either. The voice in the earlier is magnificent, but she adds certain refinements in the later one and the voice is still in surprisingly good shape for the period and much more secure than she was on the recording of Lucia di Lamermoor made earlier that year. Of course the sound is a good deal better than the early Cetra mono recording too. When it comes to the supporting casts, it’s swings and roundabouts. On the 1959 set Ferraro, though not ideal, is a good deal better than the whiney Poggi on Cetra, but Silveri and Barbieri on the Cetra are more interesting than the inexperienced and rather bland Cappuccilli and Cossotto on EMI. No doubt there are better all round casts on other complete sets, but Callas’s Gioconda is hors concours and, defeated, I’d have to say both recordings are essential.

Though her debut was a success, offers didn’t exactly flood in but Serafin was to conduct Tristan und Isolde in Venice in December and asked if she knew the role. Though she didn’t in fact know it, she said she did, thinking she would have time to learn it before rehearsals. However she was immediately summoned to an audition with Serafin, where she sight read portions of the score with the maestro at the piano. The wily old man guessed that she didn’t in fact know the role but was sufficiently impressed to offer it to her, knowing that she had time to learn it. As in all Wagner performances in Italy at that time, the opera was sung in Italian. She sang the role again in Genoa in 1948 and in Rome in 1950, but unfortunately we have no recordings. It is rumoured that one of the Genoa performances, which had Max Lorenz as Tristan, was recorded, but so far it has not surfaced anywhere and it seems unlikely it ever will. All we have of her Isolde is two performances (in Italian) of the Liebestod, one recorded at her first studio sessions for Cetra in 1949 and the other at a concert in Athens in 1957. Though probably not essential, I would not want to be without the 1949 performance at least. Callas is a warm, feminine, womanly Isolde and I like her singing of the Liebestod very much.

Her next new role was that of Turandot, which she had already learned in America prior to the aborted Chicago project. It was an opera she sang a great deal in her early career, in all 23 times. Later she admitted that she feared for her voice and dropped it as soon as she could, “because it’s not very good for the voice, you know.” Her debut in the role was in January1948 in Venice, then she sang it at the Teatro Puccini, in Udine in March. More performances in 1948 followed in the huge spaces of the Rome Caracalla and the Verona Arena, and also in Genoa. In 1949 she sang it in Naples and Buenos Aires and then never again until the EMI studio recording of 1957. All that exists of these earlier performances is a snippet of the final duet from one of the Buenos Aires performances with Mario del Monaco, in which her voice is massive and free-wheeling, easily riding the treacherous tessitura. By the time of the studio recording, it was certainly not that, but I do have a certain amount of affection for the recording, as she makes a much more interesting Turandot than most, almost making sense of an impossible fairytale character. Maybe not essential, but essential for me at least.

It may come as a surprise to find that Callas’s first Verdi role was that of Leonora in La Forza del Destino, which was her next new role and which she first sang in Trieste in 1948. The opera doesn’t figure highly in her career and she only sang it once more in Ravenna, performances which no doubt served as preparation for the EMI recording which followed a few months later. I have no idea why the role did not become part of her active repertoire, because the studio recording is one of her finest and her Leonora is unique and one of her musically most exact characterisations. Lord Harewood, writing in Opera on Record finds her to have “an unparalleled musical sensibility and imagination, subtle changes of tonal weight through the wonderfully shaped set-pieces, and a grasp of the musico-dramatic picture which is unique,” and this is a set every Verdi lover should hear.

Her next role was one that would play a much larger part in her early career. Aida was probably Verdi’s most popular opera at that time, and this no doubt contributes to the amount of times she sang it (31 times between her first performance in Turin in 1948 and her final performance in Verona in 1953). She sang it in Rovigo, Buenos Aires, Brescia, Naples, Mexico (in both her 1950 and 1951 seasons), Calabria, London, Verona and it furnished her with her La Scala debut in 1950, when she substituted for an ailing Tebaldi. She had hoped a permanent contract would follow, but it was not forthcoming and when she was asked to substitute for Tebaldi a second time in the same role, she refused saying she would only return as a permanent member of the company, which she did in the 1951/1952 season. The Mexico performances are of course well known for the stupendous high Eb Callas sings in the Act II finale. Apparently the then manager of the Mexico City season, Antonio Caraza-Campos, had a score of the opera that belonged to the nineteenth century soprano Angela Peralta. It included a top Eb interpolated into the Act II finale, and he had tried to persuade Callas to sing the note, telling her the Mexico audiences would go wild. Callas at first refused, but she had a dispute with the tenor, Kurt Baum during the dress rehearsal and then some of the other singers also complained of his boorish manner and the relentless way in which he held onto high notes. Callas decided to add the note provided none of the other singers objected, which they didn’t. Baum must have had the shock of his life when she suddenly produced a high Eb of massive proprtions, which she held ringingly throughout the orchestral postlude. She must have enjoyed the effect because she retained the note in her second season, when the tenor was Del Monaco. The live recording of this 1951 performance is definitely the one to have. It is in better sound than the earlier one and Del Monaco is a distinct improvement on Baum. The cast includes Oralia Dominguez making her local debut as Amneris and Giusppe Taddei as Amonasro and Oliviero de Fabritiis conducts an absolutely thrilling performance. One of her 1953 London performances, under Sir John Barbirolli no less, was also recorded (minus the top Eb) but I don’t find it anywhere near as thrilling as the 1951 Mexico performance. After three more performances in Verona the month after the London ones, Callas dropped the role from her repertoire, taking her final farewell when she recorded the opera in the studio under Serafin. I wouldn’t want to be without that performance either, especially for the Nile Scene where Callas and Gobbi really strike sparks off each other, ably abetted by Serafin’s superb shaping of the score.

November 30th 1948 was a momentous date, for this was the first time Callas ever sang the role of Norma, at the Teatro Communale in Florence under the baton of her beloved Tullio Serafin. Norma was quite a rarity back then, due to the paucity of sopranos who could do justice to the title role. It was considered a dramatic soprano role, though dramatic sopranos, like Milanov and Gina Cigna, who did attempt it, did not have the technique to articulate its coloratura demands, let alone fill those notes with significance. Callas returned a proper bel canto dimension to the role and she would be invited to sing it all over the world. It is the role with which she is most associated and it stayed with her throughout her career until her final performances in Paris in 1964 and 1965. She performed it 84 times and it was the role she chose for her Buenos Aires, Saõ Paulo, Mexcio, London and American debuts, both in Chicago in 1954 and at the Met in 1956. She recorded it twice in the studio, in 1954 and 1960 and we have live recordings from Mexico in 1950, London in 1952, Trieste in 1953, Rome and La Scala in 1955 and Paris in 1964 and 1965. Of the two studio recordings, both under Serafin, I actually prefer the 1960 recording, both for the better stereo sound and for the much better cast, which includes Corelli, Ludwig as Adalgisa (an unlikely bit of casting which actually pays off) and Zaccararia. In the 1954 recording Filippeschi is a shouty Pollione, Stignani too mature as Adalgisa and Rossi-Lemeni woolly-toned as Oroveso. When it comes to live recordings, none of the above are negligible (and I wouldn’t want to be without London, 1952) but the stand out recording has to be La Scala, 1955, a night on which everything seems to go right and Callas finds the purest equilibrium between art and voice. This is a Norma for all time.

After finishing her performances of Norma in Florence, Callas and Serafin went to Venice where she would be debuting as Brünnhilde in Die Walküre (8th January 1949) before going on to sing the role again in Palermo, albeit with Francescco Molinari-Pradelli in the pit. Again she would be singing the role in Italian. As with her Isolde, we unfortunately have no recording of her singing Brünnhilde.

However Callas’s next new role must have come as a surprise even to her. Serafin was to conduct performances of Bellini’s I Puritani in Venice with the coloratura soprano Margherita Carosio straight after Die Walküre and before Callas was to go to Palermo for more Brünnhildes. As it happened, Carosio fell ill and La Fenice didn’t have a substitute. It is not clear who suggested Callas, but she was called to Serafin’s hotel room one morning, when he asked her to sing the Mad Scene for the management. It was the only part of the opera she knew and she protested that her voice was too heavy for the role and that in any case she still had more Brünnhildes to sing. Serafin insisted that she could sing it and that she would learn the role in time, so three days after singing her final Venice Brünnhilde, she sang the light coloratura role of Elvira. It was a feat completely unheard of at the time and Callas soon became known as the soprano who could sing anything. Therafter she sang it in Catania in 1951, in Florence, Rome and Mexico in 1952 and in her second season in Chicago in 1955. She also retained the Mad Scene in her concert repertoire until the late 1950s. There is a live recording of her singing the role in Mexico, but, though Callas is in great voice, the rest of the cast aside from Di Stefano leave a lot to be desired, so the 1953 studio recording is essential, a much classier affair in much better sound. She also recorded the Mad Scene at her first studio sessions for Cetra and this is one of those recordings that has to be heard to be believed. Don’t miss it.

Back on schedule, Callas returned to the dramatic soprano repertoire with more performances of Brünnhilde in Palermo and Turandot in Naples before adding Kundry to her repertoire in Rome. Serafin conducted. The opera was not recorded but she also sang in a radio broadcast under Vittorio Gui in 1950, which has been preserved and issued by Warner. It is sung in Italian of course, and, though the voices come through quite well, the orchestral sound is rather murky. Still, though I might not call it essential, it is extremely interesting to hear Callas in a complete Wagnerian role and this set is much more than a mere curiosity.

Callas’s next new role might have seemed more suited to her gifts, and indeed she gives an absolutely hair-raising performance of Abigaille in Nabucco on the murkily recorded performance from Naples in 1949. The sound is one of the worst Callas broadcasts, but the voice still manages to burst through and the power and accuracy of her coloratura has to be heard to be believed. However she never sang the role again and, in later life, called it a killer. She even advised Caballé against singing it, telling her that it was completely wrong for her essentially lyric voice. “It would be like putting a precious Baccarat glass in a wooden box and shaking it. It would shatter.” Caballé heeded the advice and never sang it. Maybe Callas was right. Souliots forged her career on the role and her voice was shattered in around five years.

Callas’s next role was also by Verdi, but one which was to prove much more significant. She decided to try out the role of Leonora in Il Trovatore in Mexico, where she sang it in the summer of 1950. She at first asked Serafin to help with her preparations, but he refused as she would be working with a different conductor. Serafin did conduct her next performances in January 1951 (with Lauri-Volpi as Manrico), where she omitted some of the high notes she had interpolated in the Mexico run, but a recording of the Mexico performances shows that her musical instincts were already spot on. It is a role that has less dramatic meat than some, but displays to advantage Callas’s extraordinary musicality and sense of style and her Leonora was well received by the critics from day one. After years of imprecise singing by less technically gifted singers, it was as if an old master had been restored and lovingly brought back to life. When she sang it in London in 1953, though there was much carping about the old, shoddy production, there was none about her singing. Cecil Smith, writing in Opera Magazine, stated “For once we heard the trills fully executed the scales and arpeggios tonally full-bodied but rhythmically bouncing and alert, the portamentos and long-breathed phrases fully supported and exquisitely inflected.” Visconti remembers slipping into his box at La Scala late one evening during one of her performances of Leonora at the theatre, to find a woman already seated there, whom he didn’t at first recognise in the gloom. After Callas finished singing the Act IV aria, the woman turned to him with tears in her eyes and said, “That woman is a miracle.” The woman was Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. Later Björling, who was Manrico to her Leonora in Chicago in 1955, declared her to be “perfection”.

We have live recordings in awful sound from Mexico in 1950 and Naples in 1951 and from La Scala, in so so sound, from 1953, but despite the glory of the early, pre-diet voice, my favourite is still the 1956 studio recording, which has the inestimable advantage of being conducted by Karajan, whose pacing is brilliant, rhythms always alert and beautifully sprung, but suitably spacious and long-breathed in Leonora’s glorious arias. Di Stefano is a mite too light of voice for Manrico, but almost convinces with his unique brand of slancio and Barbieri, Panerai and Zaccaria are all excellent. Though mono, the studio sound is a good deal better than any of the live performances.

An indication of which direction Callas’s career was going to take was her next role. Sandwiched between performances of Tosca in Pisa and the Rome broadcast of Parsifal, Callas embarked on her first comic role and her first Rossini opera. At the small Teatro Eliseo in Rome in October 1950, she played Fiorilla in Rossini’s Il Turco in Italia. According to the critic Bebeducci, who was there at the opening night of the Rome production, it was “extremely difficult to believe that she can be the perfect interpreter of both Turandot and Isolde,” which was the reputation she had at that time. However, these performances might well be seen to be a turning point in her career. Though it is thought that one of the performances was broadcast (and indeed a recording of her singing Fiorilla’s Non si da follia maggiore has surfaced), nothing else has so far come to light, but we do have her studio recording of 1954, which she recorded before singing the opera again at La Scala in 1955 in a prodcution by Franco Zeffirelli. Though there are many cuts, the recording has a joy and high spirits you won’t encounter in any of the more recent recordings and is an absolute delight from beginning to end.

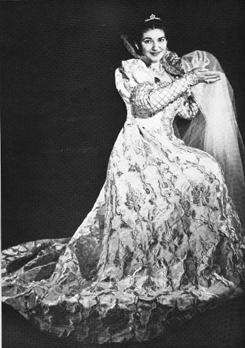

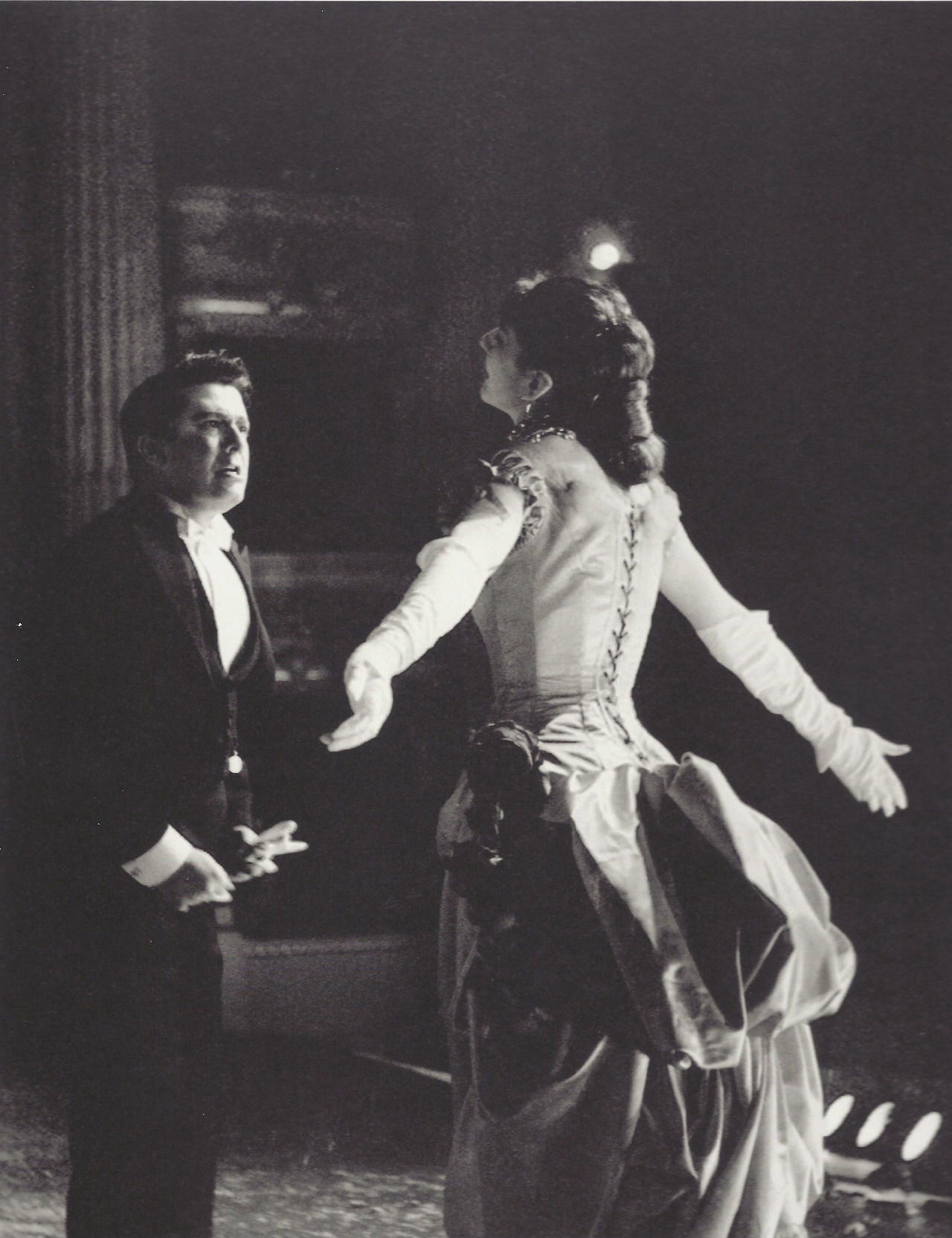

Callas turned to Verdi again for her next new role, one that she became associated with more than any other than Norma, and the one I consider the second cornerstone of her career. In Florence on January 14, 1951 she sang her first Violetta in La Traviata, a role she would eventually sing 58 times between 1951 and 1958, when she sang it for the last time in Dallas. After Florence, she sang it in Cagliari, Mexico, both in 1951 and 1952, Rio de Janeiro, Bergamo, Parma, Catania, Verona, Venice, Rome and Chicago before the famous 1955 La Scala Visconti production, which changed forever perceptions of Italian opera production. From this point on she would make more and more refinements, until she didn’t so much sing the music as experience it. The Milan production was so successful that it would be revived the following season for even more performances and in 1958 she sang it at the Met, then in Lisbon, London and Dallas.

Unfortunately her one studio recording of the opera, made for Cetra in 1953, two years before Visconti, is a somewhat provincial affair with a second-rate Alfredo and Germont under the plodding conducting of Gabriele Santini. It is amazing Callas manages so much in such dull surroundings, but her Violetta, though not yet the shatteringly moving thing it was to become, is already very affecting and she is in fine voice. Still, I always think it a shame this recording was made, for, if it hadn’t been, Callas would have been in the studio recording of 1955 under Serafin in which Antonietta Stella sang Violetta with Di Stefano and Gobbi. In fact Callas was furious with Legge for scheduling the recording before the terms of her Cetra contract allowed her to re-record it and with Serafin for agreeing to conduct it, so angry that she didn’t speak to him for some time and he is notably absent from her 1956 recording schedule.

The better of the two performances we have from Mexico unfortunately has the worst sound. In 1951 she is partnered by Cesare Valletti and Giuseppe Taddei, with Oliviero de Fabritiis the excellent conductor. Mugnai, who conducts the 1952 performance regularly loses control of the stage and the singing from all three principals is somewhat competitive. I wouldn’t call either essential, but it is worth hearing the corruscating brilliance of her coloratura in Sempre libera at that time.

La Scala 1955 with Giulini is, I think, essential, but the sound does crumble a bit in the last act, though it sounds quite good in Ars Vocalis’s transfer. The performance is certainly thrilling, with the audience bursting into spontaneous applause at her exit after Amami, Alfredo but Bastianini is disappointingly monochrome as Germont and the Act II duet suffers as a result. We have two performances from 1958, Lisbon and London, but it is London that is essential. Though not in her best voice, and reportedly suffering from a cold, she gives the most poignant, tragic and ultimately heart-rending performance of the role of Violetta you are ever likely to hear. You forget this is opera and theatre and feel you have ben confronted with real life. I doubt I will ever hear a more moving account of the role. Valletti is an ideal Alfredo, Savarese a sympathetic Germont and Rescigno conducts a superbly paced performance. Having recently acquired the Ars Vocalis transfer, this is definitely the one to go for. The sound is a good deal better than adequate.

Callas next new role was also by Verdi and, though she only sang it once more after her initial performances in Florence in May 1951, it proved to have great significance for her. I Vespri Siciliani (or Les vêpres siciliennes to give it its original French title, as it was written for the Paris Opéra) was something of a rarity at the time and is still not performed that often. The Duchess Elena is a difficult role to cast as it needs a soprano with a powerful voice who can also sing the coloratura flourishes with which the role abounds. Indeed the Siciliana she sings in the last act is often sung in concert by light-voiced sopranos who would never have the vocal power to sing the rest of the role. For Callas it was perfect and such was her success in the role that Antonio Ghiringhelli, who had thus far resisted adding Callas to the permanent La Scala company could ignore her no longer. He offered her a contract to open the 1951/1952 season in the same opera, plus Norma and Die Entführung aus dem Serail. Henceforth Milan would become both her cultural and physical home and she sang in seven consecutive seasons there. It was a period of immense artistic growth when she got to sing under the baton of Victor De Sabata, Herbert von Karajan, Carlo Maria Giulini, Leonard Bernstein and Gianandrea Gavazzeni. Visconti was first lured into the world of opera by her and would direct five spectacular productions for her. Furthermore Walter Legge got her to sign for EMI and the majority of her complete opera recordings would be made under the impimatur of La Scala. Callas had finally arrived where she wanted to be and she was soon chrsitened La Regina della Scala. We have no recording of the La Scala performances under Victor De Sabata, so we are fortunate indeed to have a recording of the Florence run, which was conducted by Erich Kleiber. The range is prodigious taking her from a low F# below the stave to an E in alt and Callas is in superb voice. It is a shame that the sound isn’t better, because the whole performance is really exciting. The tenor, Kokolios-Bardi, is the weak link, and he would be replaced by Eugene Conley at La Scala, but both Mascherini and Christoff were also engaged for their roles in Milan. Another one I would add to the essential pile.

Callas is certainly not associated with the music of Haydn and Mozart, so some will no doubt be surprised to hear that these two composers provided the music for her next two roles. Once performances of I Vespri Siciliani were over, Callas and Kleiber decamped to the tiny Teatro della Pergola for two performances of Haydn’s Orfeo ed Euridice (L’anima del filosofo) which were in fact the first ever staged performances of the opera. It was not recorded and I don’t know the opera at all, though it has since been recorded by Christopher Hogwood with Cecilia Bartoli. Oddly enough, Callas’s next new role was also a premiere. On 2 April 1952 she appeared as Konstanze in the first ever performance at La Scala of Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail (performed in Italian as Il ratto del serraglio). It is extremely unfortunate that it was not recorded as this was Callas’s only Mozart role, though we can get some idea of what a thrilling Konstanze she might have been from a couple of concert performances of Martern aller Arten (sung in Italian as Tutte le torture) the first of which (1954) can be heard on Divina’s free download Maria Callas – Soprano Assoluta. The other is a fascinating document, taken from a rehearsal for her Dallas Opera inaugural concert in 1957.

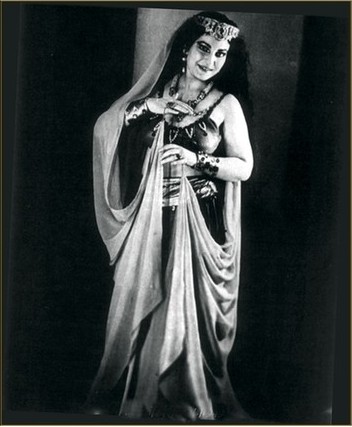

The speed at which Callas was working at that time is exemplified by the fact that just a few days after her final performances of Konstanze, and a further performance of Norma at La Scala, she was singing another new role in an opera that was virtually unknown. On 26 April 1952, she opened in Florence in Rossini’s Armida, a fiendishly difficult dramatic coloratura role that was written for Isabella Colbran. Serafin conducted a somewhat cut version of the score, but most of the cuts were made to accomodate the tenors, none of whom had the technique to sing Rossini’s florid music. The sound on the only recording we have is not good at all. Most transfers cut even more of the performance as there are about twelve minutes of music where a male voice in low pitch was dubbed over the recording. Divina have retained these sections, but it has to be admitted they are a trial to listen to. However, despite the atrocious sound, the performance absolutely has to be heard as Callas is spectacular. I doubt such corruscatingly brilliant and powerful coloratura singing has been heard before or since. Indeed it has to be heard to be believed. What a shame that, aside from a single concert performance of the aria D’amore al dolce impero in 1954, Callas never sang the role again.

Less than two months later Callas embarked on the first performances of a role that became the third cornerstone of her career, trying it out for the first time in Mexico in June of 1952. The role of Lucia in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor was at that time considered the province of light-voiced soubrettish sopranos, more intent on showing off their top notes and the opera, like most bel canto was rarely taken seriously at all. Though Callas had by this time sung Elvira in I Puritani, Armida and Fiorilla, none of those role could be considered to be part of the regular repertoire and the idea of Callas singing Lucia must have seemed absolutely crazy. However audiences in Mexcio went wild. Callas returned a dramatic dimension to the opera that most hadn’t even suspected was there. In all she sang it 43 times between 1952 and 1959 and made two studio recordings of it with Serafin at the helm, though oddly enough neither was made with La Scala forces. The first was also her first recording for EMI and was made in Florence in 1953, following perfornances of the opera there and the second stereo recording was made in London in 1959 with the Philharmonia Orchestra in Kingsway Hall. She did of course sing the role at La Scala in 1954 under Karajan, in his own production which he took to Berlin in 1955 and Vienna in 1956. The Mexico performances are not in good sound but, though the mono sound of the first studio recording is not great, it is a good deal better and Callas is in terrific pre-diet voice. This recording, with Di Stefano and Gobbi, is certainly essential, though I do have a lingering affection for the second one, which is the first recording of the opera I ever owned. The sound is excellent, and though Callas is stretched by the top Ebs, it is surprising just how good she sounds. We have two recordings of her performances with Karajan, but unfortunately the one from La Scala in 1954 is incomplete and in awful sound. The Berlin one, however, is in very good sound indeed and has achieved something of a classic status. The Berlin audiences loudly show their appreciation and Karajan even granted an encore of the famous sextet. There are quite a few options for this performance but avoid the old EMI at all costs. Warner is much better, and Divina better still. This latest Divina transfer seems to be from the same source as another that has been released by a small company called The Lost Recordings, who are releasing it on three (rather expensive) LPs. I haven’t heard this and, as I no longer have the facility for playing vinyl, probably won’t ever, but here is the link for anyone who is interested The Lost Recordings – Lucia di Lammermoor Berlin 1955.

In the same season in Mexico in 1952, Callas added another Verdi role to her repertoire, that of Gilda in Rigoletto. This too was a role more often taken by light-voiced coloraturas, but the orchestration in the last act is often quite heavy and these voices can’t really dominate the ensmble as they should in sections like the storm sequence. A more substantial voice also brings more depth to the later sections of the score after Gilda has been seduced by the Duke. Unfortunately the Mexico performances were not a great success and Callas never sang the role again apart from for the studio recording of 1956 under Serafin. We do have a recording of the Mexico performances under Mugnai, and, like the Traviata he conducted the same season, it is a bit of a mess, with stage and orchestra often getting unstuck. Callas’s musicality is never in doubt and it is often Callas who brings the ensemble back on track, even though, as we know, she probably couldn’t see the conductor at all. Maybe that helped! Di Stefano is not at his best, oversinging and casual of note values and rhythms and Campolonghi, who sings Rigoletto, is hopelessly hammy. It was obviously not a happy experience and no doubt this was the reason Callas never sang the role on stage again.

The studio recording under Serafin is another matter entirely and has almost attained the classic status of the De Sabata Tosca. Gobbi is superb in one of his best roles, Di Stefano, on much better behaviour here, is the lasciviously charming Duke to the life, and Callas perfectly characterises the virginal, but willful Gilda. You would hardly suspect that she could also be the perfect Lady Macbeth and Medea.

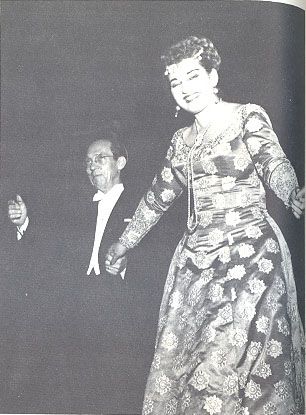

Having finsihed her season in Mexcio, Callas returned to Europe for performances of La Gioconda and La Traviata at the Verona Arena, made her debut in London at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden in Norma, before starting rehearsals for her next new Verdi role, with which she would again open the La Scala season; a role as far away from Gilda as you can imagine and one with which she is much more associated, though in fact she only sang it for this one series of performances. Macbeth was not so often performed in those days as it is now, but La Scala pulled out all the stops with a production by Carl Ebert, designs by Nicola Benois and with Victor De Sabata conducting. From the recording that exists of opening night, you’d think Callas had been singing the role for years, so complete is her mastery of its demands. In fact, it is unlikely anyone in the history of the role has carried out so acurately Verdi’s copious markings in the score, and in so doing created such a complete portrayal. There is no doubt in this performance that it is Lady Macbeth who drives the narrative. Older transfers of the recording were in pretty awful sound, but both Warner and Myto are perfectly acceptable and this is another essential Callas recording. She almost got to sing the role again at the Met, but she would not agree to a schedule that would require her to switch back and forth from La Traviata to Macbeth. Callas’s perfectly reasonable objection was that the roles required different vocal placement and switching to and from one role to another wouldn’t be good for her voice, whilst Bing claimed that he was giving her ample time to rest between performances, which wasn’t really the point. His only compromise was to switch La Traviata to Lucia di Lammermoor, a role that was even further away from the demands of Lady Macbeth. The upshot was that he publicly “sacked” Callas and even called a press conference where he very visibly tore up her contract. Sometimes I wonder if he understood anything about voices and singing at all. Apparently, once they had made up, he offered her the Queen of the Night, which would never have been within her range, and especially not at that stage in her career.

It is a great shame that Walter Legge never thought to make a complete recording of the opera with Callas and Gobbi, but the opera wouldn’t have been a safe bet back in those days and the closest Callas came to recording it was when she recorded Lady Macbeth’s three main arias on her Verdi Heroines recital disc in 1958. In any case the 1952 live recording stands as testament as to how great she was in the role, with the 1958 recital disc as a valuable supplement.

Her next new role was to become the fourth cornerstone of her career, though the opera was virtually unknown at the time. Cherubini’s Medea, if it was known at all, was only known to musicians and scholars as an opera that Beethoven had admired enormously. The version Callas sang has a complicated history as the work was originally an opéra-comique in French with spoken dialogue. It was premiered in 1797, the first performance in Italian being given in 1802. In 1855 the German composer, Franz Lachner prepared a German version for which he composed his own recitatives. This was first performed in 1909 in an Italian translation by Carlo Zangarini. This is essentially the version Callas sang, though each conductor she sang it with prepared their own slightly different versions and one should remember the opera had no performing tradition at all.

Callas first sang it in Florence in May 1953 under the baton of Vittorio Gui and had such a huge success in it that La Scala scotched their plans to revive Scarlatti’s Mitridate, Re di Ponto with her and replace it with Medea for her first opera of the 1953/1954 season. La Scala had other problems because Victor De Sabata, who was scheduled to conduct the La Scala performances suddenly fell ill just before they were due to start rehearsals. Presumably Gui, being the only other conductor to have conducted the opera in recent memory was not available and La Scala were left without a conductor for an opera that nobody knew. The young Leonard Bernstein just happened to be doing a concert tour of Italy and Callas had heard a radio broadcast of him conducting, so suggested him. He was asked if he would be prepared to take on the challenge and he agreed, and the next thing found himself rehearsing with Callas.

After these two productions, Callas went on to sing the role in Venice, Rome, Dallas, London, Epidaurus and again at La Scala, which is pretty incredible for an opera that nobody had heard of. To this day Callas is indelibly associated with the role and no other singer has been able to bring the music alive quite as well as she did. It was as if she were born to sing it. As it happens we have five live recordings (Florence and La Scala 1953, Dallas 1958, London 1959 and La Scala 1961) and one studio recording to choose from. Of these, we can safely dispense with the 1961 La Scala recording. Thoug she is still an effective Medea, the role is beginning to take its toll on her. The 1957 studio recording can also be dispensed with. Legge had no interest in the opera, so it was not recorded by EMI, though they did eventually issue the recording under licence, It was actually made by Ricordi for Mercury. At least it’s in stereo, but under Serafin’s rather staid baton it never quite catches fire the way her live performances do. In Florence in 1953, she is in magnificent voice and this is a performance in neon colours. The voice is huge and she is absolutely thrilling in the final pages, but it lacks some of the subtleties she later brings to the role. That said, I wouldn’t want to be without it. Nor would I want to be without the Bernstein La Scala performance of later that year. Callas was in mid-diet and the voice still has massive power. It is also interesting to compare the two different approaches of Gui in Florence and Bernstein in Milan. Gui’s conception is more Classical in style, while Bernstein’s fiery conducting brings it closer in style to the Romantics, rather like his performances of the later Beethoven symphonies. Both are valid and both are performances I would not want to miss. However if I could have but one example of Callas’s Medea it would be Dallas 1958. The sound of the 1959 London performance is a good deal better, but it doesn’t catch fire in quite the same way. The Dallas performance was given just after Bing had given his press conference where he had pulled the stunt of tearing up her contract and Callas was furious, granting a press conference in her dressing room in Dallas where she gave her side of the story. The event appears to have geared up the whole company because the performance is blazingly exciting from the minute Medea bursts in upon the gentle peace of the opening scenes. She also has a great supporting cast in Vickers as Giasone, Berganza as Neris, Zaccaria as Creon and Elisabeth Carron as Glauce. Rescigno, as so often with Callas, is inspired to give of his very best. This too sounds best in Ars Vocalis’s splendid transfer.

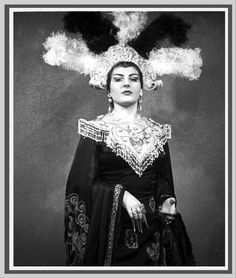

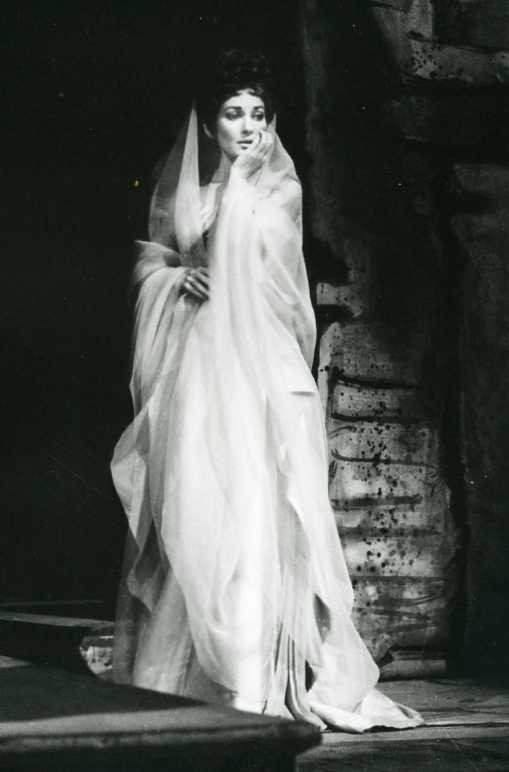

Six months later Callas embarked on her next new role, another Classical opera, but this time a much more noble heroine in the shape of Gluck’s Alceste. Like la Scala’s Medea the production was directed by Margarita Wallman. It had sets by Nicola Benois and Callas’s new, slimmer figure was costumed by Pietro Zuffi. Carlo Maria Giulini conducted his own edition of the 1776 Paris version, though translated into Italian. Callas is in splendid form and proves herself to be, in the words of Max Loppert, “a Gluck soprano of the highest order…. (who) answers every demand the role has to make” Had this recording been in better sound, I’m sure the performance would be far better known, but unfortunately it is one of the worst Callas broadcasts and listening is very difficult. For this reason, it doesn’t go on the essential pile, which is a pity as it was evidently a very fine performance.

Unfortunately we have no recordings of Callas’s next two roles. At La Scala in April 1954 she sang Elisabeth de Valois in five performances of Verdi’s Don Carlo, looking splendidly regal in Nicola Benois’ stunning costumes, and at the Verona Arena in July of the same year she appeared as Margherita in Boito’s Mefistofele. She made a superb recording of Elisabeth’s Tu che le vanita on her Verdi recital of 1958, and sang it in concert on many occasions. One should also hear her wonderful recording of Margherita’s L’altra notte in fondo al mare on her Lyric and Coloratura recital of 1954.

Shortly after this Callas would sail to America to make her US debut in Chicago in Norma, La Traviata and Lucia di Lammermoor. It should be noted that, even in 1954, she did not alternate the roles but finished one before embarking on the next. Unfortunately we have no recordings of any of her Chicago performances, though rumours persist about a recording of her 1955 Il Trovatore with Björling, but so far nothing has surfaced.

She returned to Italy wand thin and with her hair dyed blond, a short-lived experiment and she soon reverted back to her normal dark auburn. She would, yet again, be opening the La Scala season, but this time in the first of the productions Visconti mounted specially for her. The opera was Spontini’s La Vestale, Nicola Benois was again the stage designer and Pietro Zuffi designed the costumes. We have a recording of the opening night, but, if anything, the sound is even worse than that of Alceste. The opera was never repeated and Callas never returned to it, though she did record Giulia’s three main arias with Serafin on her Callas at La Scala recital. If she is less successful at bringing Giulia to life than she was Alceste, the fault lies with Spontini’s music which resists even Callas’s efforts to bring it to life. The live recording one can safely pass over, but I wouldn’t want to be without the three arias she sings on her recital disc.

Her next opera at La Scala was to have been Il Trovatore with Mario Del Monaco, but he suddenly declared himself not well enough to sing Manrico. He did, however, feel well enough to sing Andrea Chénier. Maybe he didn’t want to go up against Callas in one of her greatest roles; maybe he hoped she would step down as she didn’t know the role of Maddalena. However Callas always loved a challenge. The role of Maddalena is not very long and she agreed to learn it in time for the production. The sound of the recording we have is better than both Alceste and La Vestale, but still not particularly clear and, in any case, the opera really belongs to the tenor. Del Monaco brings the house down, showing precious little sign of any vocal indisposition. Callas does what she can with the role of Maddalena and, as usual with her, can suddenly illuminate an unexpected line of recitative. Still, I sometimes wonder why she bothered as the role offered her so little. This is another that doesn’t make it to the essentials pile, but her recording of Maddalena’s La mamma morta, which was used in the movie Philadelphia has become very popular and can be heard on her superb 1954 recital.

If Andrea Chénier can be safely passed over, her next new role and next Visconti production at La Scala would prove to be one of her greatest successes. Like Donizetti’s Lucia, Bellini’s Amina in La Sonnambula was usually sung by light-voiced coloraturas and we tend to forget that it was written for the same singer for whom Bellini wrote Norma, Giuditta Pasta. in Piero Tosi’s designs, Visconti devised a poetic, picture-book production with Callas costumed to look like the nineteenth century ballerina Maria Taglioni. The production would be revived in 1957 and she also sang it in Cologne and Edinburgh when La Scala took their production to those cities. In all she performed the role twenty-one times, always in this same production. The 1955 production yet again had Bernstein in the pit and he gave her fabulously complicated and intricate decorations to sing. Visconti had wanted to create the impression of a nineteenth century prima donna performing the role and at the end of the opera when Amina is awoken he had all the lights in the theatre brought up to full, while Callas, no longer Amina but the reigning queen of La Scala came down to the footlights and hurled her coloratura flourishes joyfully into the audience. Whatever Visconti’s idea, there is never any sense of Callas playing Amina. she simply became the poor, trusting, misunderstood village girl and her singing of Ah non credea was absolutely heart-rending.

When it comes to recordings, we have three live (La Scala, 1955, Cologne and Edinburgh 1957) and one studio, which was also recorded in 1957. If sound is your main criterion, then you would have to go for the studio recording under Votto, which has more or less the same casts as Cologne and Edinburgh. Edinburgh has reasonable sound, but Callas was not in good health and is not in her best voice. Cologne is a sifferent matter and the difference between it and the studio recording is quite palpable. Callas was in fabulous voice and the whole performance, including Votto’s conducting, catches fire in a way the studio performance does not.

However I would also always want to have the recording of the 1955 prima at La Scala, for Bernstein’s thrilling conducting and for Callas’s staggering delivery of all the extra flourishes he gave her to sing. The sound in Warner’s latest re-master is a good deal better than the old EMI and, along with Cologne, I would call this set essential.

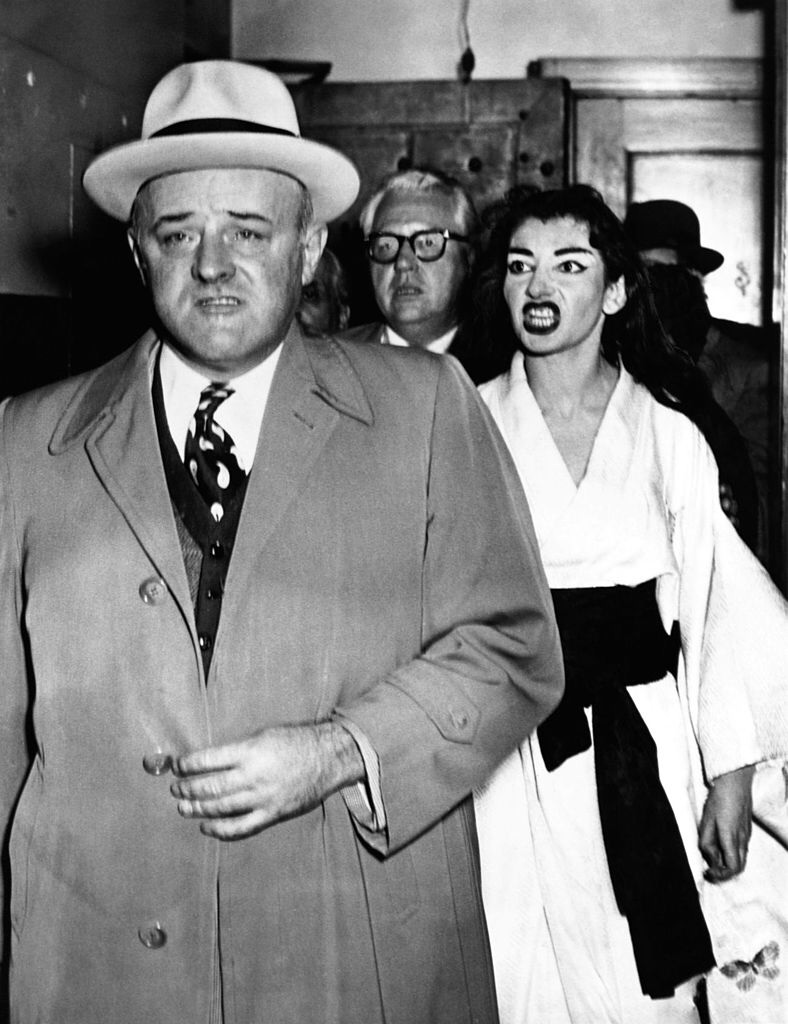

1955 would prove to be Callas’s annus mirabilis. She followed up the Visconti La Sonnnambula with the Zeffirelli Il Turco in Italia, then the Visconti La Traviata, recorded her Callas at La Scala recital disc, then sang in a concert performance of Norma in Rome, before recording three more complete operas for EMI. When the recording sessions were over Karajan took his production of Lucia di Lammermoor to Berlin, then Callas returned to Chicago for her second season, where the operas were I Puritani, Il Trovatore and her next new role Madama Butterfly, which was one of the operas she had recorded for EMI in August. The production was by the Japanese singer Hitzi Koyke and Callas had worked hard to emulate the movements of a Japanese geisha, as taught to her by Koyke. Unfortunately this was also the time when Edgar Bagarozy was trying to sue Callas for a percentage of her earnings as per a contract she had signed whilst still in America and before her Italian debut. Her counter-argument was that he had done absolutely nothing to further her career and therefore was entitled to nothing. Whatever the rights or wrongs, the Chicago Lyric Opera had agreed to have Callas closely guarded at all times so that she could not be served with due process. The two performances of Madama Butterlfy had been so successful that another was added, and it was at this performance that somehow a process server managed to get backstage and stuff a summons into the belt of Callas’s kimono just as she was exiting the stage. Callas, who would no doubt have been in a highly emotional state after such a performance, exploded with rage, a photographer just happened to be at hand to capture the moment and the rest is history. This unfortunate experience might well have contributed to the reason why Callas never sang Butterfly again, which is a great pity because the studio recording she made earlier that year with Karajan is one of her finest recordings, her portrayal utterly unique. Between them Callas and Karajan create one of the most tragic, emotionally shattering performances of the opera on disc, and one that undoubtedly goes onto the essential pile.

Back in Milan her amazing year continued when she yet again opened the La Scala season with the performance I detailed above as the greatest of all her recorded Normas.

1956 was to be less spectacular. At La Scala she sang in more performances of Norma and a revival of the Visconti La Traviata, before adding another new role in what is usually considered the only flop of her time at the theatre. Although Callas had proved she could be good in comedy, as witness her performances of Fiorilla, it was not her natural métier and as Rosina in Rossini’s in Il Barbiere di Siviglia she overplayed the comedy and her Rosina emerged as shrewish rather than coquettish or playful. Giulini, who conducted the performances, later recalled the production as the worst memory of his life in the theatre. “I don’t feel it was a fiasco for Maria alone, but for all of us concerned with the performance. It was an artistic mistake, utterly routine, thrown together, with nothing given deep study or preparation.” After that he never conducted another opera at La Scala. A recording of the production would appear to bear out his recollection, but the recording Callas made in London the following year with much of the same cast is another matter altogether and one of the most recommendable recordings of the opera. Possibly helped by Walter Legge’s production, Callas is just one of a wonderful ensemble and the whole performance, conducted by Alceo Galliera, fizzes and pops like a good vintage champagne. Another for the essential pile.

After a couple of performances of Lucia di Lammermoor in Naples and more Traviatas at La Scala, Callas was originally to have sung Kundry under the baton of Erich Kleiber at La Scala, which comes as something of a surprise at this stage in her career. However Kleiber died before rehearsals got under way, and rather than finding another conductor for Parsifal, La Scala decided to change the opera altogether to one, which was also something of a surprise. Giordano’s Fedora is an opera often sung by aging prima donnas nearing the ends of their career, which Callas was not in 1956. It’s vocal demands are slight, but it does require stage presence and good acting ability. The production was a lavish one by the Russian Tatiana Pavlova with designs by Nicola Benois, and Callas looked beautiful in the gorgeous costumes. Gavazzeni conducted and Corelli was engaged to play opposite her. It opened on May 21st 1956. We have no recording of the production, though it was rumoured for some time that Corelli’s widow had a recording locked away somewhere. As it happens, Callas sang six performances that season then never touched it again. All we have is a copious amount of photographs from the production.

With Fedora over, Callas went to Vienna with the La Scala company for three performance of the Karajan Lucia di Lammermoor. She returned to Milan to record three more complete operas (Il Trovatore with Karajan, La Bohème and Un Ballo in Maschera with Votto), then left for New York where she would finally be making her Metropolitan Opera debut in Norma, as well as singing in performances of Tosca and Lucia di Lammermoor. She would be missing the opening of the La Scala season for once. Her first Met season was not a particularly happy one. She was not in good health and not in her best voice, as can be heard from the only reecording we have from that season (Lucia di Lammermoor).

After a concert in Chicago, her first opera performances of 1957 were in London, where she returned to sing Norma again with Stignani as Adalagisa, who was nearing the end of her career and in fact retired the following year. Such was the enthusiasm that greeted the two singers that the conductor, Sir John Pritchard granted an unprecedented encore of Mira, o Norma. While in London she recorded il Barbiere di Siviglia before returning to Milan for a revival of La Sonnambula, this time conducted by Antonino Votto, who would conduct all her remaining performances of the opera, including the studio recording made around the same time.

Her next opera at La Scala was one of the most important of her career in that it could be said to have spearheaded the whole bel canto revival. Donizetti’s Anna Bolena had completely fallen out of the repertory in the middle of the nineteenth century and had only once been performed in living memory, in 1947 at Barcelona’s Gran Teatre del Liceu to mark the centenary of the opera house, which had opened with the same opera in 1847. The La Scala production was the fourth of Viconti’s productions mounted specially for Callas. The fabulous sets and costumes were by Nicola Benois. The recording we have from the opening night is one of her very best and absolutely essential Callas. I first bought it in Italy in 1976, when I was surprised to find several live recordings by Callas sitting next to the studio recordings. It was the first time I’d come across any of these ‘pirate’ recordings. I think it was on the MRF label. The EMI and Warner transfers should however be avoided as the sound is dull and muddy and they both wander in pitch. Divina’s transfer is in another world and well worth the extra outlay. An absolute must.

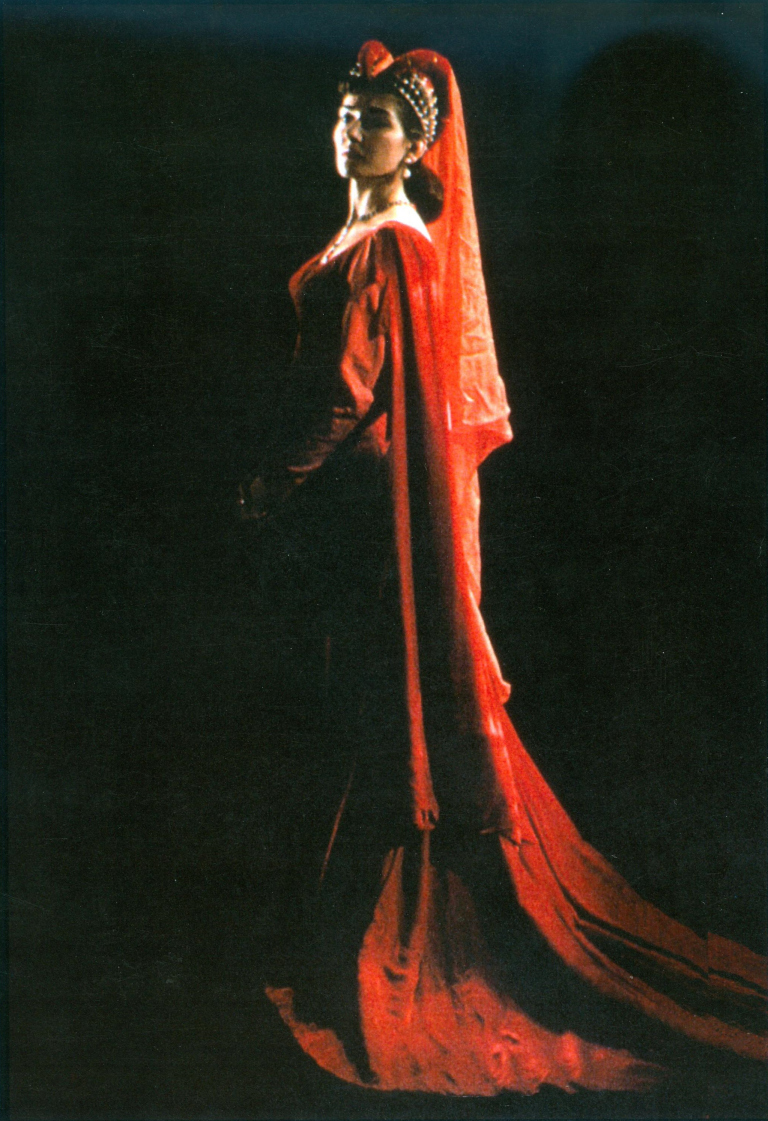

With the performances of Anna Bolena over, Callas and Visconti plunged into work on her next opera and her next new role, Ifigenia in Gluck’s Ifigenia in Tauride. Though they didn’t know it at the time, it turned out to be the last time they would work together. As usual the wonderful sets were by Nicola Benois with Callas extravagantly costumed to look as if she’d stepped out of a Tiepolo painting. Callas never really understood Visconti’s concept, averring that it was a Greek story and she was a Greek woman and that she wanted to look Greek. Still, she looked absolutely magnificent and sang the role superbly, as can be heard from the recording we have, this time in very reasonable sound. Unfortunately none of the other singers, save possibly Cossotto, who makes a brief appearance as Diana, is anywhere near her class and Nino Sanzogno conducts in somewhat soggy style. I might not call the recording essential, but one should have at least one example of her prowess in Gluck, and this is in much more comfortable sound than the Alceste from 1954.

Callas, though still busy, was not working at the white hot intenisty of those early years. The rest of the year was taken up with her usual summer recording schedule at La Scala and she travelled to Cologne and Edinbrugh with their production of La Sonnambula. She sang in Greece for the first time since the war, in a concert at the outdoor Herodes Atticus theatre in Athens, and also inaugurated the Dallas Opera with a monster concert, at which she sang the whole of the closing scene from Anna Bolena.

After Dallas she opened the 1957/1958 La Scala season with Un Ballo in Maschera, and it comes as rather a surprise to find that the this was the first time she would be singing the role on stage, though she had recorded it the previous year in the studio under Antonino Votto. The production was by Margarita Wallmann with designs by Nicola Benois, with Callas beautifully costumed again. She is in terrific voice at the La Scala prima, and I never can decide which of the two recordings I would prefer, which is essential. Both are fabulous performances. Unfortunately she never sang the role again, though she would return to Amelia’s arias for her late 1960s recitals.

You would never suspect from the live recording of Un Ballo in Maschera that Callas was on the threshhold of the biggest scandal of her career, and one that would dog her for the rest of it. She was to start 1958 with Norma at the Rome Opera on January 2nd. The opera was a gala attended by Italy’s then president Giovanni Gronchi and his wife. Callas had felt fine at the dress rehearsal on December 31, but Barbieri had already been forced to withdraw because of ill health. On the day before the gala, Callas woke feeling unwell and informed the Rome Opera of the fact, telling them they had better have a standby ready. They told her that was impossible and that she would have to sing. Reluctantly she agreed, though, in retrospect, this was a bad decision on her part. During the first act, she felt her voice slipping away from her and refused to carry on, plunging the management into chaos. There was no standby and the performance came to an abrupt halt. The attendant press was vitriolic and, following on the heels of another scandal in Edinburgh, when she had refused to sing an extra uncontracted performance of La Sonnambula, she would hence be known as the prima donna who would cancel any performance on a whim, though, if we look at her career as a whole, it is to find that her cancellation record was actually very good, and a good deal better than most singers. But still the myth persists. After the gala, the Rome Opera canceled the rest of her contract, even after she had recovered, and she never sang there again. She did sue Rome Opera for breach of contract, a case eventually settled in her favour, but by that time her career was more or less over and it was something of a Pyrrhic victory.

She returned to New York for her second season there, repeating Lucia di Lammermoor and Tosca and also singing La Traviata. Back at La Scala she won round a hostile audience in a memorable revival of Anna Bolena, but Ghiringhelli refused to welcome her back or even speak to her. She was not announced for the next season and it was clear her time at La Scala was over for the time being. Her next new role at La Scala was Imogene in another rarity, Bellini’s Il Pirata, in which she had a spectaular success alongside Franco Corelli and Ettore Bastianini. Unfortrunately we have no recording of the La Scala performances, so we are lucky that it was recorded when she got ro perform the opera in concert at Carnegie Hall in January 1959 after Bing had cancelled her Met contract. Pier Miranda Ferraro and Constantin Ego are not in the Corelli or Bastianini class, and Callas is not in her best voice, but she can still spin a Bellinian cantilena like nobody else and I prefer this recording, cuts and all, to any of the ones made since, even the EMI studio recording with Caballé.

After the La Scala Il Pirata Callas was like a queen without a kingdom. She had some fabulous successes in Lisbon, London and Dallas and also at the ancient theatre at Epidaurus in Greece, where she appeared in Norma in 1960 and Medea in 1961, but she was now appearing in more concerts than she was in staged opera. She did eventually make it up with Ghiringhelli and he invited her back to open the 1960/1961 season in Donizetti’s Poliuto, singing the role of Paolina, which would be her last new role. It is a surprise to find her taking on a role that is decidedly secondary to the tenor, who was played in these performances by Corelli, but it is possible that she lacked the confidence to come back in a big starring role. Certainly she sounds a little tentative in the recording we have of opening night, though the audience gives her a rapturous reception on her entrance. Visconti was originally scheduled to direct but he had withdrawn in protest after his film, Rocco e i suoi fratelli, was censored by the Italian authorities. He was replaced by Herbert Graf, though Viconti had already agreed the fabulous sets and costumes by Nicola Benois. On the recording we have, Callas is obviously treading very carefully, though, as always, she gives lessons in meaningful phrasing, but the opera really belongs to the tenor and Corelli is in splendid form, so this recording is essential as much for him as for her. I am not the abject Corelli fan that many are, finding him usually too lacrymose in Verdi and the verismo repertoire, so it surprises me that the two roles I find him most satisfactory in, Pollione and Poliuto, are by bel canto composers.

Callas returned to La Scala for the 1960/1961 season for her final performances of Medea, but her career was definitely winding down and, when she did appear at all, it tended to be in concert. She had expected to marry Onassis and, by all accounts, was devastated when he married Jackie Kennedy instead. Zeffirelli persuaded her to return to the stage in Tosca and Norma in London and Paris, and she returned to the Met for two performances of Tosca, but, though the Toscas had been a great success, she struggled in Norma and, after a final performance of Tosca at Covent Garden in July 1965 she never appeared on stage in an opera again. Though she embarked on a comeback tour in the 1970s, singing arias and duets with Di Stefano with piano accompaniment, her career effectively ended on July 5th, 1965.

This article discusses her stage career, but a word about the operas she recorded without ever performing them on stage and about her most essential recital discs. It is not unusual for singers to sing roles only for recording, but where she was unusual is that she can so closely enter into the sound world of the character she is playing, even without having played the role on stage. Even her Butterfly and Amelia were recorded before she played before she had stage experience in them, but they are still complete portrayals in sound. She recorded four operas that she never sang on stage; Nedda in I Pagliacci in 1954, Mimi in La Bohème in 1956, Puccini’s Manon Lescaut in 1957 and finally Carmen in 1964. Forced to choose one, I’d be hard pressed to choose between her Mimi and her Carmen, but I’d be sorry to miss her Nedda and Manon too, so would say all are necessary.

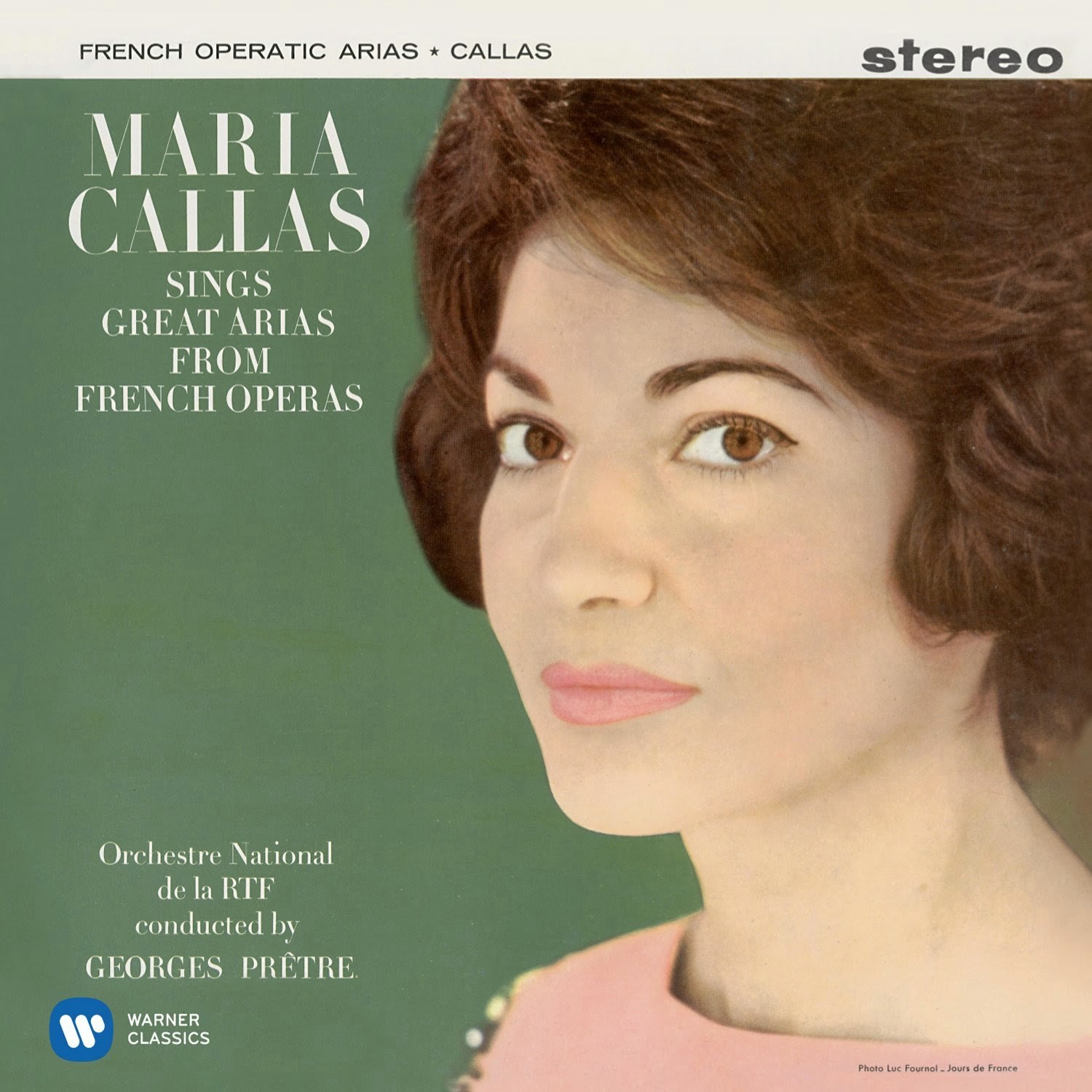

When it comes to recital discs, the late 1960s ones would be the easiest to relinquish, but I’d have to have both the French recitals. I would also want the 1954 Puccini recital and the mixed Lyric & Coloratura recital of 1954 and the Verdi recital and Mad Scenes from 1958. Divina have issued a compendium of arias from some of her live recitals and this is available as a free download, which I recommend wholeheartedly,

Between 1947, when she made her Italian debut, and her final stage performace in 1965, Callas had sung 38 different and very diverse roles, the first ten years in a crammed schedule, which must have been absolutely punishing. The speed at which she was able to work in her early years (often learning new roles in a matter of days) is absolutely incredible. Though many reasons have been put forward for her early vocal demise, including of course the intensive diet she undertook from 1953 to 1954, the intensity of her career must also be a contributing factor. I can’t think of any other singer, who has achieved so much in such a short space of time. 100 years after her birth and fifty-eight years after she last appeared on the operatic stage, she continues to fascinate and inspire argument and debate. There will always be those who cannot respond to her voice, those who just don’t like the sound of it, but equally there are those, and I include myself amongst them, who are constantly bowled over by her superb musicality and her ability to create drama and character whilst closely observing what is written in the score. I hear something new every time I listen. You will come across people who will tell you that she was more of an actress than a singer, but her legacy is in her records and we must surely now be at a stage where there are more people who didn’t see her than people who did. However great her stage presence and her acting ability, it is the music that lives on. Jon Vickers once said that the two most influential figures in post-WWII opera were Wieland Wagner and Maria Callas. That influence is still being felt to this day and I have no doubt that Maria Callas will continue to be celebrated for many more years after the present centenary.